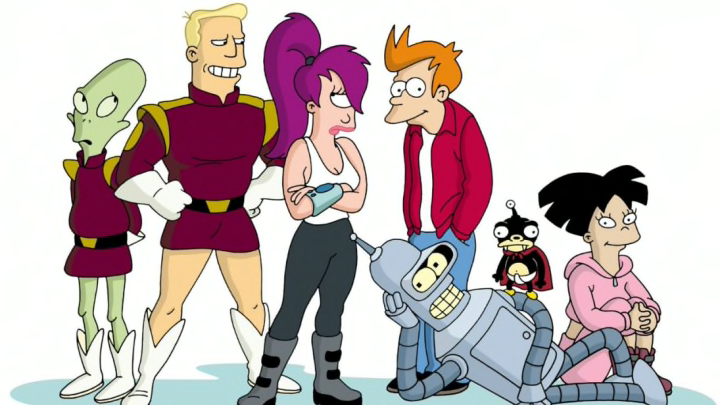

In 1999, Matt Groening followed-up the monumental success of The Simpsons with an idea for a sci-fi comedy that he’d been tinkering around with for years. With influences ranging from groundbreaking sci-fi movies like Blade Runner to shows like The Jetsons and pulpy ‘50s comics like Weird Science, Futurama proved to be yet another winner for the cartoonist. Characters like Fry, Bender, and Leela quickly became fan favorites, rivaling Homer, Marge, and the rest of Springfield for quotability. The show was also a hit with the critics, winning plenty of Annie and Emmy Awards along the way.

Never a ratings juggernaut to a larger audience, the show only lasted four seasons on Fox before being cancelled in 2003. Neither the production staff nor the series’ loyal fan base would give up on Futurama, though, and the series was revived for an additional three seasons on Comedy Central from 2008 through 2013. Here are 10 things you might not know about Futurama.

1. THE SHOW’S NAME COMES FROM AN EXHIBIT AT THE 1939 NEW YORK WORLD’S FAIR.

Though Matt Groening’s Futurama takes a comedic look at what the future might hold for us, the name is based on a very real-world version of the world of tomorrow. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Queens, GM built a mammoth attraction called Futurama, which was a scale-model city showing off the predicted wonders of 1960.

The model was the brainchild of industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes and his team of hundreds of artists and builders. It spanned an impressive 35,000 square feet, and gave audiences a glimpse at what a city might look like in the next 20 years, with the highlight being a monolithic utopia peppered with mountainous skyscrapers and a web of superhighways for futuristic GM cars to travel on. Visitors would sit in chairs that moved on a conveyer belt around the model, showing off all the wonders they could look forward to.

To pay homage to its namesake, the first thing Fry hears when he’s defrosted in the future during the pilot episode is the bellowing sound of a lab worker proclaiming “Welcome to the World of Tomorrow,” which was one of the heavily advertised themes of the fair.

2. THE THEME SONG WAS INSPIRED BY A TUNE CALLED “PSYCHE ROCK.”

Futurama’s main theme, composed by Christopher Tyng, bears a striking resemblance to the song “Psyché Rock" by French electronic artist Pierre Henry. The songs are so similar that the Futurama theme basically acts as a remix to Henry’s work. The song has also been remixed by Fatboy Slim, which is even closer to the Futurama version.

3. GETTING THE SHOW ON THE AIR WAS A DIFFICULT PROCESS FOR MATT GROENING.

Though Matt Groening and the team over on The Simpsons have the freedom to mostly govern themselves, getting Futurama off the ground was a different story. When asked by Mother Jones in 1999 about getting the show on the air, Groening said, “It has been by far the worst experience of my grown-up life.”

He further explained that, “The second they ordered it, they completely freaked out and were afraid the show was too dark and mean-spirited, and thought they had made a huge mistake and that the only way they could address their anxieties was to try to make me as crazy as possible with their frustrations.”

Despite the battles with the network, Groening and his team didn’t cave, saying, “I resisted every step of the way. In one respect, I will take full blame for the show if it tanks, because I resisted every single bit of interference."

4. CO-CREATOR DAVID X. COHEN IS A MATH WHIZ.

When Groening was developing Futurama into a pitch, he had one key Simpsons writer in mind to collaborate with: David S. Cohen. Cohen (who is credited as David X. Cohen for Futurama) was known for some of the most popular Simpsons episodes of the mid-‘90s, including "Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie," "Lisa The Vegetarian," and "Much Apu About Nothing."

“After I assembled a few hundred pages of ideas, I got together with David Cohen, one of the writers and executive producers on The Simpsons, who is also a lover of science fiction and has a great knowledge of science and mathematics,” Groening told Mother Jones.

The emphasis on mathematics may sound odd, but it became a hallmark of the series. Dealing with sci-fi plots allowed Cohen to bring a certain authenticity to some of the more complex episodes; he was also able to sneak in all sorts of esoteric mathematical jokes for the like-minded viewers. This is similar to how math played a role on The Simpsons for years without ever becoming distracting to casual viewers.

Cohen’s mathematical background goes far beyond the norm. He graduated from Harvard with a degree in physics, and from the University of California, Berkeley, with an M.S. in computer science. This knowledge gave way to plenty of in-jokes, including the creation of a numerical-based alien language and countless background gags that only the brainiest viewers would have a shot at deciphering.

5. ZAPP BRANNIGAN WAS GOING TO BE VOICED BY PHIL HARTMAN.

The character of Zapp Brannigan was originally written with actor Phil Hartman in mind for the voice, but he was tragically killed before he would have begun recording. The role then went to Billy West, who also voices Fry and Professor Farnsworth. In an interview with The New York Times, West says he based his Brannigan on disc jockeys from the ‘50s and ‘60s. There's also a bit of Hartman's signature, Troy McClure-esque sound in there.

6. JOHN DIMAGGIO ORIGINALLY AUDITIONED FOR PROFESSOR FARNSWORTH USING BENDER’S VOICE.

Figuring out what Bender would sound like wasn’t an easy task for the folks in charge of Futurama. Would it be a human voice, or something more synthesized like Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet? The crew auditioned dozens and dozens of voice actors in an attempt to find the perfect Bender, with no luck.

At the same time, voice actor John DiMaggio was auditioning for a role on the show against his agent’s wishes, who worried about both the money and contract being offered. At first he auditioned for the role of Professor Farnsworth, using a boorish, drunken voice he partially based on Slim Pickens. The voice didn’t work for the professor, but according to the DVD commentary for the show’s pilot, the producers asked him to try it out for Bender. The voice instantly clicked, leading to the creation of the show’s breakout character.

7. THE NIXON LIBRARY EVENTUALLY CAME AROUND TO HIS HEAD BEING IN A JAR.

Richard Nixon famously proclaimed that the media wouldn’t have him to “kick around anymore” back in 1962; little did he know the jabs would keep coming for decades in the real world, and centuries into the fictional future as a nightmarish version of the former president with his head preserved in a jar was proclaimed President of Earth in Futurama.

With Billy West providing the jowly voice of the former Commander-in-Chief, Nixon became a villain for a whole new generation. And the Richard Nixon Library wasn’t very happy about it at first.

“[E]arly on in the show the network got a letter from the Richard Nixon Library saying they weren’t pleased with his portrayal and would we consider not doing it,” Cohen told WIRED.

But a few years later, things changed.

“We didn’t really stop, however, because we liked it, but the strange thing is that … a few years later we got another letter from the Nixon Library saying can we provide some materials because they’re going to do an exhibit about Nixon in popular culture and they’d like to include Futurama, so they came around.”

8. WRITER KEN KEELER INVENTED A NEW THEOREM JUST FOR THE SHOW.

In addition to Cohen, Futurama is staffed by a roster of Ivy League graduates with backgrounds in science and math. But while writing one episode, the staff had created a plot so complex that the crew soon found itself stumped.

The episode was “The Prisoner of Brenda” from the sixth season, and it involved a brain-switching machine that could swap the minds of any two people that stepped into it. There was only one problem: once used, the machine couldn’t be used twice to swap the same two minds back to normal. This means numerous pairs of other characters would have to use the machine in a roundabout plan to restore everyone’s mind to their proper body.

Though the idea sounded like a winner to the writers, Cohen recalled that they soon realized they had to create a mathematical explanation that could get everyone’s mind back. It was like a nightmarish SAT problem for the staff. That is until writer Ken Keeler, who has a PhD in mathematics, created a completely unique theorem that proved this plot was possible.

“Ken comes in the next morning with a stack of paper and he said, ‘I’ve got the proof,’ and he had proven that no matter how mixed up people’s brains are, if you bring in two new people who have not had their brains switched, then everybody can always get their original brain back, including those two new people,” Cohen told WIRED. “So I was very excited about this, because you rarely get to see science, let alone math, be the hero of a comedy episode of TV.”

In the episode, the mathematical heroes that solve the problem are none other than the Harlem Globetrotters, who are among Earth’s elite intellectuals in the 31st century.

9. THE SHOW’S USE OF FORESHADOWING IS INTENSE.

Futurama touts more than just science and math cred; the show is also one of the more intricately plotted animated series of the past 20 years. The show is notorious for leaving morsels of foreshadowing in episodes that pay off weeks, months, or even years down the road.

Plot points like Fry being his own grandfather and Leela’s mutant heritage were all hinted at before they became reality, but the most obscure piece of foreshadowing came right in the pilot episode. It happens right as Fry is leaning back in the chair that would “accidentally” topple over and send him into the cryogenic chamber, leaving him thawed out in the 31st century. For a brief moment, a shadow flashed across the screen with no explanation—at the time, it likely went unnoticed by many viewers.

Fast forward to the season 4 episode “The Why of Fry,” and we learn that the shadow belonged to Nibbler, who had traveled back in time to 1999 to push Fry into the chamber because he was the key to stopping an alien invasion in the 31st century. It's just one example of the type of intricate world-building that the writers of the show poured into every episode.

10. EACH EPISODE TOOK ABOUT A YEAR TO COMPLETE.

Every episode of Futurama is a labor of love, with each joke and frame of animation put under intense scrutiny. Because of this, there is a lot of work involved in the show—about a year’s worth for each episode.

“It's usually somewhere in the vicinity of a year from the beginning of a Futurama episode to the day when you can see it on TV,” David Cohen told The Atlantic.

This starts with a story idea, which is then assigned to a writer for an outline and first draft. From there, the first draft is dissected in the writers’ room on a “word-by-word, scene-by-scene basis.”

Then it’s recorded by the actors—like an old-timey radio show, according to Cohen—and then it’s given to the animators. That process involves animatics and final animation, which can take around six months to finalize.