With no more troops or supplies to move after the end of the Civil War, the country's railroads became home to another army—that of the hobos. The ever-increasing web of rails nationwide would go from 45,000 miles before 1871 to nearly 200,000 by 1900, making it easier for the poorest of working-class folk, many of whom were veterans, to hitch a ride on a train and travel from state to state looking for employment. These hobos were soon a familiar sight coast to coast.

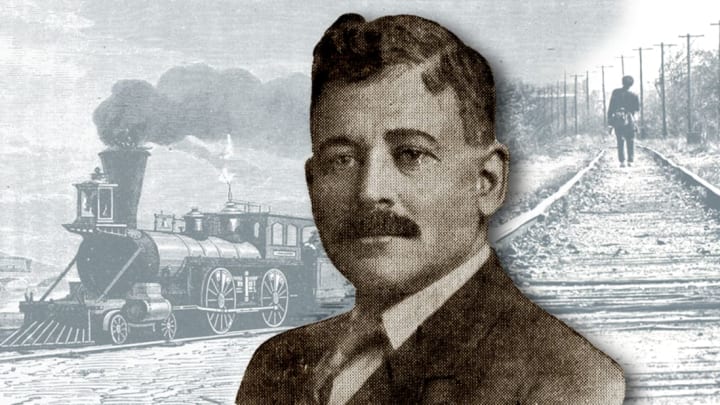

The journeys of these destitute travelers quickly caught on in the popular culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, creating a romanticized view of this unique lifestyle. It was a time when writers like W. H. Davies and Jack London parlayed their hoboing experiences into literary notoriety, while Charlie Chaplin's "Little Tramp" would become one of the most recognizable movie characters of the 20th century. Among these wandering folk figures was a man with a sense of showmanship and a keen eye for branding: Leon Ray Livingston—a writer, lecturer, and transient who would go on to dub himself "King of the Hobos."

What we know about Livingston's early life comes solely from the books he wrote, which often read like tall tales designed to help build his mystique. According to Livingston, he was born in August 1872 into a family from San Francisco that he described as "well-to-do," but at age 11, misbehavior at school led him down a different path in life. On the day after his 11th birthday, his teacher sent him home with a note detailing his bad behavior, which was to be signed by Livingston's father. The boy didn't show his father the note that night, and when he spotted his teacher heading toward his house the next morning, Livingston snuck out of the house and kept moving. He wouldn't fully stop for decades.

Livingston says he left his house that day armed with a .22-caliber rifle and a pocket full of money—some stolen from his mother, some a birthday gift from his uncle. From there, his life became an odyssey of riding the rails, hopping on steamers, and taking on odd jobs as he traversed a country in the midst of an industrial revolution. Years later, Livingston would famously brag that he traveled 500,000 miles while only spending $7.61 on fares.

In his decades on the road, he took to writing about his experiences, eventually self-publishing around a dozen books about his adventures; the most comprehensive was Life and Adventures of A-No. 1: America's Most Celebrated Tramp. Published in 1910—nearly 30 years after he left home—this book includes tales of his early life as a hobo, including one globe-trotting adventure in his first year that found him working aboard a British trade ship that set off from New Orleans for Belize, where he jumped ship and began working for a mahogany camp.

Livingston's Central American exploits include anecdotes about the working conditions in the British mahogany camps, his repeated (but failed) attempts to desert his employers and head home on their dime, feasting on "roasted baboon," and his near-fatal run-in with something he called Black Swamp Fever (which could be a reference to malaria). The writing is colorful and no doubt romanticized, making it hard to separate facts from the legend Livingston aimed to enhance.

It was after his return trip to America that Livingston was christened with the nickname that would help him become something bigger than a lowly transient: A-No. 1. In his book, Livingston said the moniker was given to him by an older companion named Frenchy, who said:

"Every tramp gives his kid a nickname, a name that will distinguish him from all other members of the craft. You have been a good lad while you have been with me, in fact been always 'A-No. 1' in everything you had to do, and, Kid, take my advice, if you have to be anything in life, even if a tramp, try to be 'A-No. 1' all the time and in everything you undertake."

He also told Livingston to carve this new nickname into each mile post he passed on his journey, letting the world know who'd traveled here before them. This piece of advice gave the legend of Livingston more longevity than he could ever imagine: In the 21st century, people are still finding "A-No. 1" scribbled under bridges.

Anthropologist follows trail of century-old hobo graffitihttps://t.co/EGbsLOcoqL pic.twitter.com/anZEi8rzR4

— CP24 (@CP24) May 30, 2016

In addition to signing their nickname, the wandering tramps would also draw up symbols to alert others of possible danger or hospitality ahead. In his 1911 book Hobo-Camp-Fire-Tales, Livingston provides drawings of 32 of these symbols and what they all mean—including signs for "This town has saloons," "The police in this place are 'Strictly Hostile,'" and "Hostile police judge in this town. Look out!" It's not completely clear if Livingston played a role in creating this hobo code, but he is credited with preserving these symbols and bringing them to the attention of a curious American public.

As Livingston became more of a cultural figure, he seemingly took an interest in leading people away from the tramp life. His books would often begin with a warning, telling readers, "Wandering, once it becomes a habit, is almost incurable, so NEVER RUN AWAY, but STAY AT HOME, as a roving lad usually ends in becoming a confirmed tramp." He then finished, saying this "pitiful existence" would likely end with any would-be tramp in a "pauper's grave." These warnings could be a well-meaning public service announcement, although scholars say they can also be read as Livingston's attempt to enhance the danger of the lifestyle to create even more intrigue about his exploits (and sell more books).

Always a showman, Livingston understood publicity as well as any celebrity at the time; in his travels he would often seek out local reporters, becoming the subject of numerous newspaper articles and magazine interviews around the country. Taking pride in his exploits, he carried a scrapbook of his journeys around with him, which included personalized letters and autographs from notable figures such as Thomas Edison, George Dewey, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft.

His influence among the community was far-reaching, even capturing the imagination of a young Jack London, author of White Fang and The Call of the Wild, during his formative years. London had reached out to Livingston about his lifestyle in the late 19th century, and the two adventured together, as chronicled in Livingston's book From Coast to Coast with Jack London, which was published in 1917, a year after London's death.

Despite the freight-hopping and steamer trips and odd jobs, Livingston wasn't hurting for money; for him, hoboing was a spiritual necessity, not a financial one. When he would seek some stability during his travels, he could often be found staying at Mrs. Cunningham's Boarding House in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, where he would write many of his books. In The Ways of the Hobo, he claimed the house became "a veritable Mecca to chronic hoboes," including old friends like "Hobo Mike" and "Denver Johnny," who sought out his counsel and companionship.

In 1914, Livingston married a woman named Mary Trohoske (sometimes spelled Trohoski), and he settled down—as best a tramp could—in a house in Erie, Pennsylvania. His later years were spent working various jobs—including at electric and steel companies around Erie, though one source places him in real estate. While he stayed relatively put in his later years, Livingston did travel the lecture circuit to speak out against the lifestyle that defined him. With the country in the throes of the Great Depression, the warnings Livingston wrote about the hobo lifestyle in each of his books had transformed into full-on speeches against tramping. (Sadly, his lectures don't seem to have survived.)

Rumors persist about Livingston's final days. Some claim that he continued his traveling ways toward the end, dying in a train wreck in Houston, Texas, in 1944, but this is likely confusion with a 1912 wreck that killed one of his impersonators. According to most accounts, Livingston passed away due to heart failure in his home on April 5, 1944 around age 71, with his wife by his side. But for a man who lived to mythologize his own story, a little ambiguity about his end is only fitting.

Livingston's fame has waned significantly since the first quarter of the 20th century. He's only re-emerged in the mainstream a few times, most notably when Lee Marvin played A-No. 1 in the 1973 movie Emperor of the North, based on Livingston's travels with Jack London and on London's own book The Road. Though little-remembered now, Livingston was part of a fleeting moment in American history—a time when the country was getting the first real glimpse of itself as an interconnected nation, and when someone who lived by wandering could be the stuff of folklore.