Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 298th installment in the series. Read an overview of the war to date here.

DECEMBER 25, 1917: LAST CHRISTMAS AT WAR

“Christmas was, of course, but a sorry season,” wrote Evelyn, Princess Blücher in Berlin, doubtless speaking for many across a war-torn continent, in her diary in January 1918. She added, “The days come and go, and we have already crossed the borderland and have left the gloom of the old year, only to enter the darkness of a new one. Every hour brings its fears, disappointments, and vague hopes, so that there is but little time for collecting one’s scattered ideas.” Her feelings reflected the general mood in Germany, judging from the testimony of Herbert Sulzbach, a German soldier on leave in Frankfurt. “The consequences of three and a half years of war are weighing heavily on the home country, and you see a great deal, in fact, a never-ending amount of distress," he wrote in his diary on January 12, 1918.

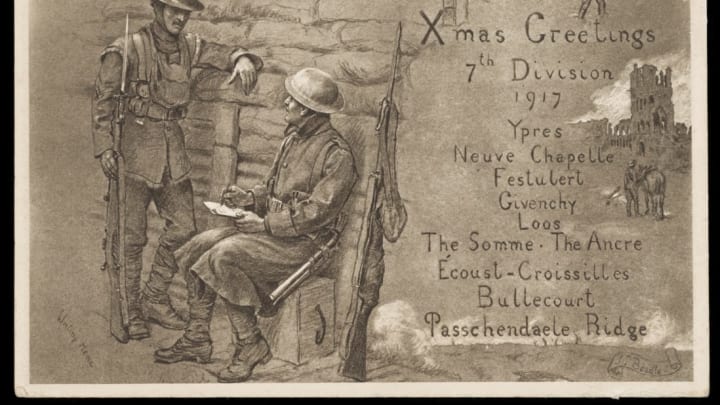

The Christmas of 1917, the fourth during the war (after Yuletides in 1914, 1915, and 1916) would also be the last—although no one could know that, or be able to foretell the epic events that would unfold before 1918 at last brought peace to a shattered world. Jack Martin, a British soldier deployed to Italy to help shore up Italian defenses after Caporetto, wrote in his diary on December 31, 1917:

Thus ends the year of grace 1917, a year of frightful agony and slaughter, of shattered hopes and broken lives; a year where humanity has sunk to incredible depths of inhumanity; a year that has brought tears to the eyes of the Recording Angel … Our souls have been scorched and seared by contact with hell and we yearn for the healing oil of peace.

While most ordinary people longed for peace, they expressed feelings of helplessness in the hands of fate and forces far larger than themselves. The war had long ago taken on a life of its own, defying human comprehension or control, and the end seemed to retreat further and further into an indefinite future. Vera Brittain, now approaching her third year as a volunteer nurse’s aid, recalled that by the beginning of 1918, “I no longer even wondered when the war would end, for I had grown incapable of visualizing the world or my own existence without it.”

RARE REPASTS

It’s worth noting that Christmas was still a time for joy and good cheer, at least for soldiers who were lucky enough to be “in billets” or on leave, where military authorities did their best to provide a traditional Christmas meal. This was easier for the Allies, as food was generally more plentiful in Britain and France than in the Central Powers, where the Allied “starvation blockade” and disruptions to agriculture and transportation were taking a heavy toll. (By the end of the war it is estimated that around 400,000 Germans had died from malnutrition or starvation.)

John Tucker, a British soldier, described festivities with plenty of food and alcohol (which, however, left him with a week-long hangover):

As the officers’ servants were taking their mess-cart to the large YMCA canteen at Arras for their Christmas supplies, we persuaded them to bring us two cases of port wine, some Vermouth, and to lend us a dozen glass tumblers. The cooks did an excellent job and conjured up a large roast dinner of turkey, vegetables, and Christmas pudding. Every man was given a small Bible from the Queen. These came in useful later as cigarette papers. We also managed to get a few Dutch cigars. We settled down at our table after dinner, with tumblers full of port, plenty of bread, cheese, and pickles, and naturally all got very jolly.

Ivor Hanson, a British gunner, described their Christmas repast near Ypres: “A whole pig had been roasted and there were potatoes, onions, Brussels sprouts, Christmas pudding, apples, oranges, dates, nuts, cigarettes, and a double rum issue. During this orgy musical selections were given on a portable Decca gramophone.” (Below, a New Zealand commander carves the Christmas turkey).

The holiday was even more bountiful for American troops, who benefited from the country’s vast breadbasket as well as the government’s determination to keep soldiers (and therefore their voting relations at home) as comfortable and happy as possible. And, of course, concerned family members also lavished gifts on soldiers with care packages. Vernon Kniptash, an American soldier with the Rainbow Division in France, wrote in his diary, “Mumsey and Maude sent me heaps. God bless ‘em both. Lordy, but I’m happy. Had a scrumptious dinner, duck, dressing, mashed potatoes, gravy, biscuits, jam, pickles, slaw, doughnuts, peach pie, cake, figs, and coffee. Then they passed out chocolate, cigarettes and cigars. I’m so full I’m in misery.”

AMERICANS AT WAR AND AT SEA

Christmas at war was a new experience for most Americans, following the country’s entry into the conflict in April 1917. Like their European peers, ordinary American soldiers found the holiday an occasion for reflection. William Russel, an American soldier in the transport section of the U.S. Army Air Force in France, wrote home the day after Christmas, “It is the first Christmas that I have ever been separated from those whom I love, and instead of being a day of festivity, it has changed to a day of thought, and one that will linger in my memory for years, if I am spared.” Later, he noted, “Christmas and New Years have passed, and I must confess it is a sort of relief to have them over. Although both were happy days in so far as the hospitality and very kind treatment by friends went, yet there was an indescribable lonesomeness which made them strange.” (Below, volunteers fill stockings at a U.S. Army hospital in France).

While Christmas was a time for contemplation, the war remained an enigma with undeniable but sometimes inexpressible significance for humanity and the individual’s inner life. Julia Stimson, an American volunteering as a nurse in France, wrote home in December 1917:

Oh I wish I could tell you what all this is meaning, as I see it. Maybe some day I can, for every day I am seeing things more clearly, but as yet I can’t write it all down—after a while perhaps. We talk about it, from time to time, some of us, every once in a while, and oh, dear people, no greater thing can ever come into any one’s life than this chance of ours—to get away from little things and self and to know what the things of the Spirit are, and what true values really are.

In 1917 thousands of Americans, soldiers and civilians alike, spent the holiday at sea aboard ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean, rendered even more unusual and nerve-wracking by the constant threat of U-boat attack. In fact U-boats sank 400,000 tons of shipping in December 1917 alone—a decrease from earlier in 1917, thanks to the Allies’ adoption of convoy tactics as well as the vigilance of destroyers armed with depth charges.

By the end of 1917 the shipping struggle was finally starting to turn in the Allies’ favor, due in large part to the massive production of American shipyards, which churned out millions of tons of new shipping. However, net losses from U-boat attacks continued through the first quarter of 1918, and from the perspective of the British Admiralty, the end of 1917 was one of the most perilous moments of the war. For ordinary British and French people, the continuing losses during this period resulted in shortages and rising prices for things like sugar and tobacco.

Even when Allied convoys made it through unscathed, the experience of crossing the Atlantic under constant threat was unique and unforgettable for American soldiers. Morris Dargan, a railway engineer from Oregon, wrote to his sister describing safety measures on board:

You have asked me whether or not we saw any submarines. No, we didn’t see any, but all through the submarine zone we wore life preservers at all times. We wore them at meals, on the deck, in the hold and in bed. We had lifeboat drill a couple of times each day and were not allowed to throw anything overboard, lest a “sub” would sight it and follow our trail. We were not permitted to talk loudly or to smoke on deck after night, etc.

As always, travelers were impressed by the majesty of the sea, tempered by the menace below the waves. Daniel Poling, a Christian lecturer and temperance advocate en route to the Western Front to observe conditions and speak to troops at YMCA canteens, recalled his winter crossing:

The great liner had reached the danger zone. She drove ahead through the night with ports closed and not a signal showing. Under the stars, both fore and aft, marines watched in silence by the guns. Each man wore or had by him a life-preserver, and there was silence on the deck. Quietly I stood by the rail, and watched the waves break into spray against the mighty vessel’s bow. The phosphorescent glow bathed the sea in wondrous light all about; only the stars and the weird illumination of the waves battled the darkness; there was no moon. It was hard to realize that out there somewhere silent watchers waited to do us hurt.

Not everyone was headed to Europe. Josephine Therese, an American singer returning to America in December 1917 after being interned in Germany for thirteen months, described her Christmastime voyage back to the U.S., which managed to have some exciting incidents even though no U-boats attacked the ship:

We took the safest possible course, swinging in a wide circle northward, which carried us close to Greenland, and the voyage was uninterrupted by Prussian sea perils and otherwise uneventful, except for a few minor incidents, such as a knife duel between two Bulgarians in the steerage, which ended by one throwing the other overboard, never to be seen again … Despite this tragedy, we arrived with the same number of passengers … for a baby was born en route—also in steerage.

Though spending Christmas aboard ship was certainly novel, most people who found themselves at sea on the holiday were not eager to repeat the experience. Briggs Adams, an American soldier crossing the Atlantic, noted that the common affliction of seasickness made it hard to spread holiday cheer:

The day before Christmas it began to get pretty rough, and that night the ship rolled so that it was impossible to sleep a wink, for it was a continual fight to keep from rolling out of the bunk. Half the ship was sick [on] Christmas. They decorated the dining room up a bit with paper and flags, but it only made the absence of Christmas greens the more noticeable. There wasn’t one Christmasy thing the whole day … never again will I spend Christmas on the sea.

ENCOUNTERING HORROR

Of course, the ocean voyage was only the beginning of the new experiences facing American soldiers and civilians caught up in the maelstrom of war. Like their European counterparts before them, their first encounters with death and destruction at the front would be etched in their memories forever, although later these horrors became commonplace and routine. Preston Gibson, an American serving in the ambulance corps, wrote home about the scenes around first-aid posts near the Aisne in November 1917:

Near one called Bascule, about half-a-mile from the third line, we found a great number of dead piled up in the road—horses and men. Some of the bodies had to be pulled off the road in order to make it clear for traffic. Besides the bodies that were lying stretched in different positions, some with their heads off, some with chests torn and ripped open, I saw two mounds of dead Chasseurs at Ferme Hemeret, about 15 or 20 in each mound, one body piled on top of the other. Some lay as if in slumber; the faces of others were contorted by the great agony they had passed through; others were in most grotesque positions.

Sudden, sweeping personal losses were a regular part of life in wartime, as Americans were discovering. Coningsby Dawson, an American who had volunteered in the Canadian Army, wrote home in November 1917:

Last week I met one of my gunners on leave. He was standing on the island in Piccadilly Circus. I learnt from him that every officer who was with me at the battery when I was wounded has since been wiped out. Even some who joined since have been done for … Among the killed is poor S., the one who was my best friend in France. You remember that he had a young wife and his first baby was born in February. He used to carry the list of all the people I wanted written to if I were killed, and I had promised to do the same for him … All this was told me casually in the heart of London’s pleasure with the taxis and buses streaming by.

Though French and British troops were more familiar with conditions at the front and somewhat inured to the awful sights, the death and destruction never ceased to horrify even the most hardened soldiers (below, British troops on the Ancre, early 1918). John Jackson, a British soldier, described shell-holes behind the front in December 1917:

These holes were often 10 or 12 feet deep and full up at this time with dirty, slimy water. At the bottom of them in many cases could be seen the bodies of dead men and mules, together with parts of ammunition wagons, the whole creating a stench that was rotten, and sickening.

Francis Buckley, a British soldier, recorded similar scenes near Passchendaele, Belgium, in mid-December 1917:

The shell-holes were often full of German dead—I counted nearly 100 within a quarter of a mile of Dan Cottages. And on the forward wooden tracks used by our transport, the ground reeked like a slaughter-house. Fragments of everything just swept off the tracks. The limbs and bodies of the pack-mules lying sometimes in heaps, sometimes at intervals, all along the route.

Conditions at the front often required regular contact with corpses. After recovering from his holiday hangover, the British soldier Tucker described the sickening but very common state of trenches near Cambrai, recently the scene of a short-lived British success with a surprise attack by tanks:

Often there was a soft, rubbery feeling under foot similar to standing on an inflated mattress; this would indicate a dead body in the bottom of the trench, having been trampled deeper in the mud by the feet of perhaps hundreds of men passing over it. Sometimes an arm or leg would be protruding. No one had time or inclination to do anything about this. It soon became a common experience and accepted with indifference.

Tens of thousands of women volunteering as nurses in field hospitals as well as larger convalescent centers at home also directly experienced the horrors of war, treating badly wounded and dying men. Still serving as a V.A.D. in France, Brittain wrote home on December 5, 1917:

We have heaps of gassed cases at present who came in a day or two ago; there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case—to say nothing of 10 cases—of mustard gas in its early stages—could see the poor things burnt and blistered all over with great mustard- colored suppurating blisters, with blinded eyes—sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently—all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke … and yet people persist in saying that God made the war, when there are such inventions of the Devil about.

THE SPECTER OF DISEASE

Disease was a common killer from the beginning of the war, with typhus, dysentery, malaria, and gas gangrene killing hundreds of thousands and incapacitating millions more across Europe, the Middle East, and other theaters of war. Over the course of the war typhus, carried by ubiquitous body lice, killed 200,000 people in Serbia alone, out of a total population of 3 million, as well as 60,000 Habsburg prisoners of war. During the Russian Civil War, just beginning, typhus would kill an estimated 3 million people from 1918-1922.

But even these losses would pale in comparison to the scourge nature would unleash on the world in 1918-1920, in the form of the highly contagious and breathtakingly deadly influenza epidemic. Although it became known a the “Spanish flu” due to reports of the high death toll in neutral Spain, where the press was free from wartime censorship, the flu was a global pandemic that killed anywhere from 50 to 100 million people—more than the war’s own total of around 20 million.

The flu was a natural phenomenon, but wartime conditions undoubtedly played a major role in enabling its spread, and may also have made it more deadly. Throwing together millions of soldiers—most of them young men who had never been far from home and therefore lacked immunity to new diseases—in cold, drafty barracks and tents, with primitive communal canteens, latrines and showers, provided perfect breeding grounds for the flu as well as other diseases. The movement of millions of human beings around the world also provided an ideal vector for the virus to reach distant populations. And bringing together large numbers of people from different places may have enabled several flu viruses to swap DNA and become even more dangerous (the flu epidemic actually unfolded in two main stages, the second far more lethal).

As 1917 drew to a close, no one could have predicted the unprecedented global flu epidemic about to scour the planet, but many observers noted the sharp uptick in communicable disease around this time. Already, during the American Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa in Mexico, army doctors recorded outbreak of a mysterious ailment causing severe bronchitis in troops stationed in northern Mexico and along the southwestern border region; some of these troops later returned to Fort Riley, Kansas—site of the first recorded flu outbreak in March 1918.

There’s no way to know whether the two events were linked, but there’s little doubt that all the conditions for an epidemic were in place, including food and fuel shortages in Europe which left people physically weakened and cold (below, snow at Hooge, Belgium, on New Year’s Day). Although better off than their counterparts in the Central Powers, Allied soldiers and civilians often went hungry too, due to shortages and supply disruptions. Martin, the British soldier in Italy, wrote on December 10, 1917:

The rations are so short that the cooks have to be most careful in issuing them—as long as every man gets the same there can be no complaint … Before allowing any plate to be removed we demand to know if any one has any objection; thus we avoid the possibility of any subsequent criticism or complaint … We cannot say that we are suffering actual starvation but most assuredly we know the pangs of continual hunger. For breakfast we get a plate of porridge or a slice of bacon, for dinner, bully stew but no potatoes and once or twice we have had boiled rice.

In Paris in January 1918, Ferdinand Jelke, an American liaison officer born in France, noted that in the city, “Deaths from pneumonia have occurred by dozens daily.” On the other side of the Atlantic, the winter of 1917-1918 was one of the coldest on record in North America, blanketing even southern camps in snow and freezing rain. On December 1, 1917, August P. Gardner, a former congressman from Massachusetts and the son-in-law of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, wrote to Joseph P. Tumulty, a secretary to President Wilson, about conditions at Camp Wheeler, Georgia:

There have been 100 deaths from pneumonia and 11 deaths from other causes at this camp. Of this number 96 have occurred within the last three weeks. To my mind the explanation is fairly simple. The following are the conditions as I see them: Between October 16th and 30th, we received about 10,000 drafted men from Camp Gordon, Camp Pike, and Camp Jackson. With the exception of about 3000 from Camp Pike, they came without overcoats, in cotton outer garments, and cotton underclothes; some without blouses. None of them had had experience in sleeping out-of-doors and none were accustomed to camping out … Being from rural areas, many had never had measles, and this disease spread rapidly. Better soil in which to sow the seeds of pneumonia could not be imagined. The Base Hospital at Camp Wheeler is calculated for 500 patients, and over three times this number of sick men were of necessity thrust upon it.

Similarly, Paul Elliott Green wrote home from Camp Sevier, South Carolina, on November 22, 1917, “We are quarantined for an indefinite time on account of measles, pneumonia, and meningitis. Many poor boys have died, as many as six in one night.” And Kenneth Gow, an officer in training in Camp Wadsworth, wrote home on December 14, 1917:

The thermometer has remained in the vicinity of 6 degrees since the first of the week, and we have about 8 inches of snow on the ground. It is impossible to keep warm. Everything is frozen up, and we have to melt snow for water to wash in. On Tuesday afternoon the regiment was suddenly ordered out on an inspection evening parade by some Regular Army inspecting officers. We stood for an hour shivering in a blinding snowstorm from the North, with a biting wind driving the snow into our eyes and ears.

THE LOOMING RECKONING

Even while unaware of the impending natural disaster, the Allies had plenty to fear as 1918 dawned. Italy’s defeat at Caporetto and Russia’s withdrawal from the war opened the way for Germany to transfer around a million men to the Western Front, where they would unleash a titanic assault in the spring in an attempt to settle the war before large numbers of American troops began to arrive in Europe. No one could predict the shape or direction of the German attack, but there was no question—it was coming, and the final result would depend in large part on how quickly America could ride to the rescue.

Mildred Aldrich, an American retiree living in a village outside Paris, confided in a letter home, “I don’t deny that I study the map today with a nervous dread of what is before us on the road.” Morris Dargan, the railway engineer from Oregon, warned in a letter home that “next spring … will mark the most momentous hours of the whole war.” Russel, the American soldier serving in the air force supply corps in France, noted, “The French are so down to bone and sinew, and have so little physical strength left … of course, there is great anxiety as to what the late winter and early spring may bring.” And Katharine Morse, an American volunteering in canteens for soldiers, noted disturbing talk that France was all but beaten:

And underneath all this runs another rumor, still darker, still more disquieting. The French, the gallant French, they say, are "laying down.” They are ready to make peace at any price. They are played out, sick to death of it all! “Forty-two months in the trenches!” cried a sergeant en permission last night; “It is enough! I am through. Let the Americans do it!” And this feeling, they tell us, is widespread. The people see our soldiers day after day, in the training camps, inactive. “What are they here for?” they are asking. “Why don’t they fight? Are they going to wait until it is all over?”

On the other side, the recent victories in Russia and Italy held out the hope that all the sacrifices might not be in vain after all. Adolf Hitler, then a regimental messenger on the Western Front, later wrote in Mein Kampf:

Towards the end of 1917 it seemed as if we had got over the worst phases of moral depression after the front. After the Russian collapse the whole army recovered its courage and hope, and we were gradually becoming more and more convinced that the struggle would end in our favor … The Italian collapse in the autumn of 1917 had a wonderful effect; for this victory proved that it was possible to break through another front besides the Russian.

But the Germans were in a race against time, and not just because of the prospect of American troops starting to arrive in force. They also faced growing anger on the home front, due to the murderous toll of the war, which by the beginning of 1918 had claimed the lives of around 1.3 million soldiers, and the terrible privations faced by civilians, increasingly blamed on the German government and military as well as the enemy. In her final diary entry of 1917, Blücher noted with unease, “If the war continues much longer the people will follow Russia’s example and take the matter into their own hands.”

This would be the year of reckoning.

See the previous installment or all entries, or read an overview of the war.