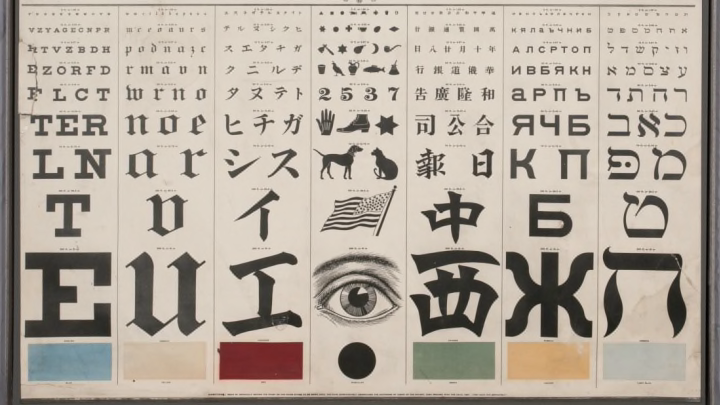

At the turn of the 20th century, San Francisco was a diverse place. In fact, Angel Island Immigration Station, located on an island in the San Francisco Bay, was known as the “Ellis Island of the West,” processing some 300,000 people coming to the U.S. in the early 1900s. George Mayerle, a German optometrist working in the city at the time, encountered this diversity of languages and cultures every day in his practice. So in the 1890s, Mayerle created what was billed as “the only [eye] chart published that can be used by people of any nationality,” as The Public Domain Review alerts us.

Anticipating the difficulty immigrants, like those from China or Russia, would face when trying to read a vision test made solely with Roman letters for English-speaking readers, he designed a test that included multiple scripts. For his patients that were illiterate, he included symbols. It features two different styles of Roman scripts for English-speaking and European readers, and characters in Cyrillic, Hebrew, Japanese, and Chinese scripts as well as drawings of dogs, cats, and eyes designed to test the vision of children and others who couldn't read.

The chart, published in 1907 and measuring 22 inches by 28 inches, was double-sided, featuring black text on a white background on one side and white text on a black background on the other. According to Stephen P. Rice, an American studies professor at Ramapo College of New Jersey, there are other facets of the chart designed to test for a wide range of vision issues, including astigmatism and color vision.

As he explains in the 2012 history of the National Library of Medicine’s collections, Hidden Treasure [PDF], the worldly angle was partly a marketing strategy on Mayerle’s part. (He told fellow optometrists that the design “makes a good impression and convinces the patient of your professional expertness.”)

But that doesn’t make it a less valuable historical object. As Rice writes, “the ‘international’ chart is an artifact of an immigrant nation—produced by a German optician in a polyglot city where West met East (and which was then undergoing massive rebuilding after the 1906 earthquake)—and of a globalizing economy.”

These days, you probably won’t find a doctor who still uses Mayerle’s chart. But some century-old vision tests are still in use today. Shinobu Ishihara’s design for a visual test for colorblindness—those familiar circles filled with colored dots that form numbers in the center—were first sold internationally in 1917, and they remain the most popular way to identify deficiencies in color vision.

[h/t The Public Domain Review]