Ovaries are only about the size of large grapes, but they’re one of the most important organs in the female body. Their primary responsibilities include producing eggs and secreting sex hormones that promote fertility. In this way, the future of humanity depends on them. Read on to learn more about these tiny but mighty organs.

1. THEY’RE THE FEMALE GONADS.

Go ahead and laugh, but gonads was a scientific term long before it became slang for a man’s testicles. It actually refers to the reproductive glands of both sexes: ovaries for women, and testes for men. When an embryo is in the early stages of development (around the seventh week), its gonads have the potential to develop into either female or male sex organs through a process called sexual differentiation. By this point, the sex has already been pre-determined by chromosomes (XX or XY), and in the absence of a Y chromosome, the gonads turn into ovaries. One study of adult mice found that ovaries could be turned into testes by deleting a single gene called FOXL2, which is constantly working to suppress the development of male anatomy in mammals. However, it's unknown what effect the modification of this gene would have on humans.

2. THEY’RE CONTROLLED BY THE BRAIN.

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland both play pivotal roles in ensuring the ovaries function as they should. Neither is located anywhere near the ovaries, though. “If you put your finger between your eyes and shoved it backwards into your brain, first you would knock into your pituitary gland, which is a little pea-sized gland,” Randi Epstein, a New York City-based medical doctor and writer, tells Mental Floss. “And if you kept ramming backwards, then you would hit the hypothalamus.” (Of course, she doesn’t recommend actually trying this.)

The hypothalamus is the hormone control center, while the pituitary gland is called the body’s "master gland" because it controls the thyroid and adrenal glands, as well as the ovaries and testicles. Essentially, the hypothalamus tells the pituitary gland to send hormones to the ovaries, and the ovaries respond by secreting their own batch of hormones. A signal is then sent back to the hypothalamus to let it know if the levels of estrogen and progesterone are too high or too low. The cycle then continues, but we don't fully understand what triggers the hypothalamus and kicks off the process in the first place, Epstein says.

3. IT’S HARD TO ACCURATELY PREDICT WHEN OVARIES WILL KICK OFF MENOPAUSE.

Because of the previously mentioned unknowns, there’s no way of telling when puberty or menopause will occur. In the latter case, scientists have been looking at different genetic markers in an attempt to predict when the ovaries will shut down the processes of menstruation and ovulation—otherwise known as menopause—but "nothing is definitive" right now, according to Mary Jane Minkin, an obstetrician-gynecologist in New Haven, Connecticut, who also teaches at the Yale School of Medicine.

However, family history and age offer some clues. The average age for menopause in the U.S. is 51, but if all the women in your family went through menopause in their forties, there’s a good chance you will, too. Women who have had hysterectomies may also go through menopause one or two years earlier than they normally would, even if they have otherwise healthy ovaries. That's because the surgery is believed to reduce the flow of blood to the ovaries, resulting in a lower supply of hormones and therefore earlier ovarian failure.

4. SMOKING CAN ALSO TRIGGER EARLIER MENOPAUSE.

The effects of smoking on internal organs aren’t pretty, and the ovaries are no exception. “Smoking rots ovaries,” Minkin tells Mental Floss. “Basically, if you want to go through menopause earlier, smoke cigarettes.” Doing so can accelerate the onset of menopause by one to two years, and studies have shown that smoking hurts overall ovarian function as well.

5. THEY CHANGE SHAPE OVER TIME.

Ovaries get bigger and morph into the shape of an almond when girls reach adolescence, eventually reaching roughly 1.4 inches in length. Later in life, once menopause has occurred and the ovaries have fulfilled their purpose, they dwindle to under an inch long. “They just sort of poop out and they shrink, so the size gets exponentially smaller,” Minkin says.

6. WHEN A GIRL IS BORN, HER OVARIES HOLD ALL THE EGGS SHE’LL EVER HAVE ...

Female fetuses can carry as many as 7 million oocytes (immature eggs) in their ovarian follicles, and by the time they’re born, that number drops to about 2 million. Here's a mind-boggling fact: If a woman is pregnant with a girl, that means she’s also carrying her potential grandchildren, too.

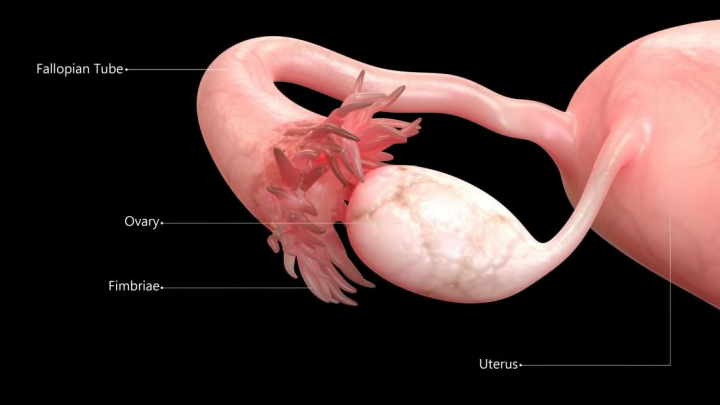

Many of these eggs die off before a girl reaches reproductive age, though. By the time she starts going through puberty, she has about 300,000 left. About 1000 or so eggs are lost each month after that. When it’s all said and done, only about 400 mature eggs go through ovulation, at which point they’re dropped from the ovaries, through the fallopian tubes, and into the uterus.

7. ... BUT STEM CELL RESEARCH COULD CHANGE THAT.

Research in recent years has suggested that ovarian stem cells could someday be used to grow new egg cells, or to delay or stop menopause in women. Both of these tasks have already been successfully carried out in mice. "If we could gain control of the [human] female biological clock ... you could arguably delay the time of ovary failure, the primary force behind menopause,” researcher Jonathan Tilly told National Geographic in 2012.

For now, women faced with a diminishing supply can have their unfertilized eggs frozen through the process of cryopreservation. It’s meant to improve a woman’s chances of conceiving at a later date, but it isn’t guaranteed to work. “It’s getting better, but it’s hardly perfect,” Minkin says. “You can freeze the eggs, but you don’t know how viable they’re going to be in the long-term.”

8. SCIENTISTS HAVE CREATED 3D-PRINTED OVARIES FOR MICE.

In 2017, scientists used “porous scaffolds from a gelatin ink” to 3D-print synthetic ovaries for mice, The Guardian reported. Those ovaries were then filled with follicles containing immature egg cells, which allowed the mice to give birth to healthy babies. Scientists hope this technique will someday be used to restore fertility to women whose ovaries have been damaged by cancer treatments.

9. OVARIES CHILL OUT ON BIRTH CONTROL PILLS.

Oral contraceptives prevent ovulation by providing all the estrogen and progesterone that the body needs. With the ovaries’ job taken care of, they get to go on “vacation,” Minkin says. When contraceptive pills are used for five or more years, they reduce a woman’s risk of ovarian cancer by 50 percent. That’s because “funky things can happen” during ovulation, at which time the ovaries are at greater risk of an aberration, Minkin says. On the other hand, if the ovaries aren’t releasing eggs, there’s less of an opportunity for mistakes to happen. The ovaries are also less exposed to naturally occurring hormones that may promote the growth of cancer.

10. SOME CHRONIC CONDITIONS AFFECT THE OVARIES.

One of the most common problems affecting the ovaries are cysts. These fluid-filled sacs can form when an egg isn’t properly released from an ovarian follicle, or if the empty follicle sac doesn’t shrink after it bursts open to release an egg. Fortunately, these cysts often go away on their own. They only become a problem if they grow, or multiple cysts form. Strange things can happen, though. In one recent case, surgeons found a cyst containing a miniature skull and brain tissue inside the ovary of a 16-year-old girl. Yes, you read that right. It's called a teratoma —from the Greek word for monster—and it happens when the reproductive cells go rogue and start developing their own way.

Another disorder that can sometimes affect the ovaries is endometriosis. This occurs when tissue that’s similar to the endometrium, which lines the uterus, starts growing somewhere outside the uterus and causes a chronic inflammatory reaction. It can attach to the bladder, bowel, ovaries, or other areas. Symptoms may be minimal, severe, or somewhere in between, and the tissue can be removed through a minor surgery if needed.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is another fairly common problem, and it’s caused by a hormonal imbalance that in turn creates problems for the ovaries. Ovulation may not go as smoothly, periods can be irregular, and cysts can develop. Since there’s no cure, it’s a lifelong condition, but the symptoms can be managed.

11. CUNNING SALESMEN ONCE SOLD ANTI-AGING OVARY TONICS.

Miracle elixirs made from animal ovaries and testes were a big “money-making fad” in the early 20th century, Epstein writes in her book Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything. According to the sales pitch at the time, sex organs give life, so it’s only logical that they would help boost your energy and libido. “We were taking rabbit ovaries, crushing them up, desiccating them, and using them as a fertility or anti-aging treatment,” Epstein tells Mental Floss. One of the first “cures” for menopause and menstruation symptoms wasn’t much better, either. The main active ingredient was alcohol.

12. BIRDS HAVE JUST ONE FUNCTIONAL OVARY.

Unlike their dinosaur ancestors, birds have only their left ovary. Scientists theorize that birds lost an ovary over the course of evolution because it helped reduce their weight, making it easier for them to fly. This explains why dinosaurs laid loads of eggs, but birds lay just a few at a time.

13. SOME ANIMALS CAN SWITCH SEXES BY CHANGING THEIR OVARIES.

All clownfish are born male, but they’re able to change sex at will. This is because they have both mature testes and immature ovaries, the latter of which can develop if the alpha female in a school of fish dies. (As Business Insider points out, a scientifically accurate Finding Nemo would have been significantly more disturbing.)

Parrotfish can change sex as well—mostly from female to male. During this transition, the ovaries dissolve and testes are grown. “In general, for species where big males can control access to females (think harem), it pays to be female when small (you get to reproduce with the dominant male) and then turn into a male when you are big enough to duke it out with a competing male to win access to a group of females,” writes Marah Hardt, author of Sex in the Sea.