The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 136th installment in the series.

July 31-August 1, 1914: France Mobilizes, Germany Declares War on Russia

When Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II agreed to order general mobilization on the afternoon of July 30, 1914, he unwittingly started the clock on German mobilization. The Schlieffen Plan concentrated German forces in the west for an attack on Russia’s ally France. This allotted precisely six weeks to defeat the French before shifting east to face the Russians, on the assumption the Russians would take around that long to collect their troops across their empire’s vast distances. Once Russian mobilization began, each passing day left the Germans less time to defeat the French and increased the likelihood that Russian armies would overwhelm token German forces guarding East Prussia, opening the way to Berlin.

As August 1914 began, a continental war pitting Germany and Austria-Hungary against Russia and France was basically inevitable. The key question now was whether the two remaining Great Powers, Britain and Italy, would join in.

July 31: Panic Spreads Across the Globe

As Europe hurtled towards war, world trade and finance were paralyzed by waves of panic rippling out across the planet. Shortly after 10 a.m. London time on Friday, July 31, the London Stock Exchange closed to prevent mass sell-offs, and a few hours later the governing committee of the New York Stock Exchange decided to suspend trading on the NYSE; this was the first time since 1873 that the exchange was closed. The move received support from the White House and the U.S. Treasury and, after a brief, disastrous attempt to reopen on August 3, the NYSE remained closed until December, although some investors found ways to continue trading informally. Meanwhile, Congress voted to make $500 million in emergency funds available to banks to avert a credit collapse.

Over the course of the day the German government advised merchant shipping lines to cancel all sailings in order to keep the ships from falling into enemy hands, while the French government requisitioned the steam liner La France, nicknamed the “Versailles of the Atlantic,” for use as a troop transport (later, hospital ship). And the German Social Democratic Party, fearing a government crackdown on pacifist organizations, secretly sent co-chairman Friedrich Ebert —later the first president of the Weimar Republic—to Switzerland with most of the party’s funds for safekeeping.

But all this activity was the mere backdrop for the drama on the main stage.

The Machinery of War

On the morning of July 31, German ambassador to St. Petersburg Friedrich Pourtalès stormed into the Russian Foreign Ministry brandishing a red piece of paper. It was the mobilization decree ordering reservists to report for duty, which had been posted around the city the previous night. Pourtalès told Foreign Minister Sazonov’s assistant that “The proclamation of the Russian mobilization would in my opinion act like a thunderbolt... It could only be regarded by us as showing that Russia was bent on war.”

Pourtalès immediately requested a personal audience with Tsar Nicholas II, whom he begged to cancel the mobilization order:

I particularly emphasized that the mobilization was a threat and a challenge to Germany… When I remarked that the only thing which in my opinion might yet prevent war was a withdrawal of the mobilization order, The Tsar replied that… on technical grounds a recall of the order issued was no long possible… I then attempted to call the Tsar’s attention to the dangers that this war represents for the monarchic principle. His Majesty agreed and said he hoped things would turn out right after all. Upon my remarking that I did not think this possible if Russian mobilization did not stop, the Tsar pointed heavenwards with the words: “Then there is only One still can help.”

Both Tsar Nicholas II and Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov continued to insist that Russia was willing to negotiate with Austria-Hungary and emphasized that just because Russian forces were mobilizing didn’t mean Russia was going to declare war. This was true enough, as it would take weeks for Russian forces to concentrate for an attack. Unfortunately, they seemed to believe that the same was true of Germany—that is, that Germany could also mobilize without immediately going to war. Of course this wasn’t true, as the German Schlieffen Plan called for an immediate invasion of Belgium and northern France, with the first incursions scheduled to take place just hours after mobilization began. Needless to say, neither man was privy to the details of Germany’s strategy.

After his fruitless meeting with the Tsar, Pourtalès hurried to inform Berlin of Russian mobilization via telegram. The news arrived around noon, as Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg was meeting with War Minister Falkenhayn and chief of the general staff Moltke (who was in close contact with the Austro-Hungarian chief of the general staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf, during this period). The three men immediately agreed that the chancellor should ask Kaiser Wilhelm II to proclaim the “imminent danger of war,” triggering pre-mobilization measures. Before ordering mobilization, however, the Germans would give Russia one last chance to back down. At 2:48 p.m., the Kaiser sent a personal telegram (in English, which both men spoke, often referring to each other by their nicknames) to Tsar Nicholas II stating:

On your appeal to my friendship and your call for assistance began to mediate between your and the austro-hungarian Government. While this action was proceeding your troops were mobilised against Austro-Hungary, my ally… I now receive authentic news of serious preparations for war on my Eastern frontier. Responsibility for the safety of my empire forces preventive measures of defence upon me. In my endeavours to maintain the peace of the world I have gone to the utmost limit possible. The responsibility for the disaster which is now threatening the whole civilized world will not be laid at my door. In this moment it still lies in your power to avert it. Nobody is threatening the honour or power of Russia who can well afford to await the result of my mediation… The peace of Europe may still be maintained by you, if Russia will agree to stop the milit. measures which must threaten Germany and Austro-Hungary. Willy

In his reply the Tsar reiterated that mobilization didn’t necessarily mean Russia was going to war, and promised Russia would remain at peace as long as negotiations continued—once again missing the point that, for Germany, mobilization did indeed mean war:

I thank you heartily for your mediation which begins to give one hope that all may yet end peacefully. It is technically impossible to stop our military preparations which were obligatory owing to Austria's mobilisation. We are far from wishing war. As long as the negociations with Austria on Servia's account are taking place my troops shall not make any provocative action. I give you my solemn word for this. I put all my trust in Gods mercy and hope in your successful mediation in Vienna for the welfare of our countries and for the peace of Europe. Nicky

After this informal and inconclusive exchange between the autocrats, at 3:30 p.m. on July 31, German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg sent a formal ultimatum to Russia stating:

In spite of still pending… mediation, and although we ourselves have taken no mobilization measures, Russia has today decreed the mobilization of her entire army and navy, that is also against us [in addition to Austria-Hungary]. By these Russian measures we have been compelled for the security of the Empire, to proclaim imminent danger of war… mobilization must follow unless within twelve hours Russia suspends all war measures against ourselves and Austria-Hungary…

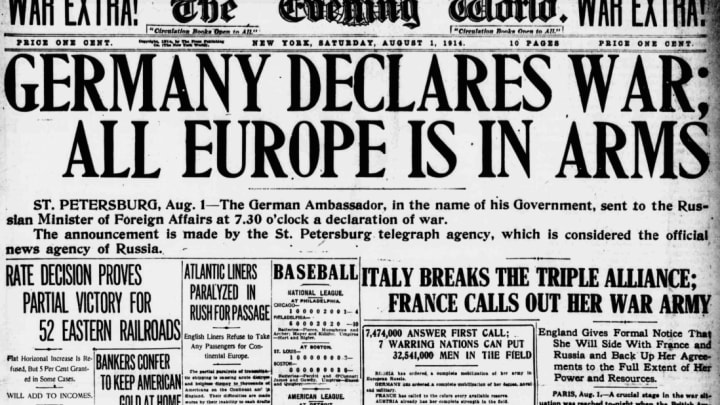

Credit: Chronicling America

Trying to Sway Britain

In truth, this last-minute “diplomacy” was just as much about laying blame for the war for both domestic political consumption and in order to sway public opinion in Britain, who were still on the sidelines. As part of these public relations campaigns, both sides circulated messages justifying their actions and presenting evidence of their own innocence.

Thus in the early afternoon of July 31, Kaiser Wilhelm II sent a personal message to Britain’s King George V portraying Germany as the unwitting victim: “I just received news from chancellor that… this night Nicky has ordered the mobilization of his whole army and fleet. He has not even awaited the results of the mediation I am working at and left me without any news, I am off to Berlin to take measures for ensuring the safety of my eastern frontiers where strong Russian troops are already posted.”

Later that day, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg outlined a similar argument for the German ambassador to London, Prince Lichnowsky, to present to the British press:

The suggestions made by the German Government at Vienna were entirely on the lines of those put forward by England, and the German Government recommended them for serious consideration at Vienna… While the deliberations were taking place, and before they were even terminated, Count Pourtalès announced from St. Petersburg the mobilization of the whole Russian army and navy… We were compelled, unless we wished to neglect the safety of the Fatherland, to answer this action, which could only be regarded as hostile, by serious counter-measures… Please use all means to induce the English press to give due consideration to this sequence of events.

Similarly, Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count Berchtold circulated a statement to all the Great Powers, stating, “Since the Russian Government has ordered mobilization on our frontier, we are driven to military measures in Galicia. These measures have a purely defensive character and are taken purely under the pressure of Russian provisions which we greatly deplore, as we ourselves have no aggressive intentions towards Russia…”

France Delays Mobilization

Germany was also doing its best to cast blame on France, however unconvincingly. Simultaneously with the ultimatum to St. Petersburg, in the afternoon of July 31, Berlin sent an ultimatum to Paris demanding to know whether France would remain neutral in a war between Germany and Russia, in the hopes that a French refusal would give them a justification to invade. In order to make the ultimatum as offensive as possible—and therefore more likely to provoke a firm “no”— the Germans demanded that the French guarantee their neutrality by turning over the key fortresses of Toul and Verdun to German occupation forces for the duration of the war.

Of course there was zero probability of this happening, but the French cabinet realized that they couldn’t simply reject the absurdly insulting (but carefully calculated) “peace offer” out of hand, as the Germans would use this as proof that France “chose war.” So Premier René Viviani crafted a proud, perfectly French non-answer to deliver the next day: “The Government of the Republic will have regard to its own interests.”

Meanwhile, in order to highlight their peaceful intentions, the French cabinet rebuffed chief of the general staff Joseph Joffre’s request for immediate mobilization, instead authorizing only “covering forces” to guard against a sudden German surprise attack. The politicians also insisted that Joffre pull his troops ten kilometers back from the frontier in order to avoid any accidental contact with German forces.

Jaurès Assassinated

Nonetheless, the war claimed its first French victim that night, albeit indirectly. At 9:40 p.m. the great socialist leader Jean Jaurès was eating dinner with a handful of supporters in a café called Le Croissant, located on the corner of Rue Montmartre and Rue Croissant. A 29-year-old French nationalist, Raoul Villain, approached him from behind and shot him twice in the head.

Villain, a member of a nationalist student group devoted to the recovery of the “lost provinces” of Alsace-Lorraine from Germany, apparently opposed Jaurès because of his socialist pacifism. He wasn’t the only one; on July 23, the far-right newspaper Action Française stopped just short of calling for his assassination, and conservatives were angered by a speech Jaurès gave on July 25 warning that war was imminent and criticizing the French government for backing up Russia.

Robert Dell, a friend and supporter, was sitting near Jaurès when the shots rang out:

Then we saw that M. Jaurès had fallen sideways on the bench on which he was sitting, and the screams of the women who were present told us of the murder… A surgeon was hastily summoned, but he could do nothing, and M. Jaurès died quietly without regaining consciousness a few minutes after the crime. Meanwhile the murderer had been seized and handed over to the police, who had to protect him from the crowd which had quickly collected in the street… A more cold-blooded and cowardly murder was never committed. The scene in about the restaurant was heartrending; both men and women were in tears and their grief was terrible to see… M. Jaurès has died a victim to the cause of peace and humanity.

The assassination of Jaurès, coming on top of assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the resulting diplomatic crisis, and the shocking Caillaux verdict seemed to reflect a world spinning out of control. The looming external threat overshadowed France’s deep political divisions, and there were no riots in the working class districts of the French capital as many feared.

A King’s Last-Minute Plea

With both sides claiming to want peace and pointing fingers at each other, it’s no surprise the British remained confused and ambivalent on July 31. Despite his growing mistrust of Germany, Foreign Secretary Edward Grey was also critical of Russia for mobilizing first, as he indicated in a conversation with the French ambassador, Paul Cambon, on the evening of July 31: “This, it would seem to me, would precipitate a crisis, and would make it appear that German mobilization was being forced by Russia.”

Above all, Grey was determined to look after British interests, and in a fraught situation he was careful to define these as narrowly as possible. Chief among them was the concern that both sides should respect the neutrality of Belgium, which, lying directly across the English Channel, was a cornerstone of British national security. On the evening of July 31, Grey sent notes to both Germany and France, asking whether they would respect Belgian neutrality. The French government responded by midnight that France would uphold the treaty guaranteeing Belgian neutrality—but Germany was strangely silent.

Even at this late stage, following the German threat of war, Grey still hoped against hope that a peaceful solution was possible, leading to yet another desperate last-minute peace attempt. In the early morning of August 1, Grey, along with Prime Minister Asquith and First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, woke King George V and asked him to send a personal telegram to Tsar Nicholas II, which read:

I cannot help think that some misunderstanding has produced this deadlock. I am most anxious not to miss any opportunity of avoiding the terrible calamity which at present threatens the whole world. I therefore make a personal appeal to you to… leave still open grounds for negotiation and possibly peace. If you think I can in any way contribute to that all-important purpose, I will do everything in my power to assist in reopening the interrupted conversations between the Powers concerned.

By the time the telegram was decoded and delivered to the Tsar on the afternoon of August 1, it was already too late.

August 1: Chaos Across Europe

The morning of August 1 found Europe in chaos. In Germany, the government ordered banks to stop allowing cash withdrawals, but the French government failed to take similar measures in time, leading to runs on banks across the country. Philip Gibbs, a British war correspondent, described one such incident in Paris:

I passed its doors and saw them besieged by thousands of middle-class men and women drawn up in a long queue waiting very quietly – with a strange quietude for any crowd in Paris – to withdraw the savings of a lifetime or the capital of their business houses. There were similar crowds outside other banks, and on the faces of these people there was a look of brooding fear, as though all that they had fought and struggled for, the reward of all their petty economies and meannesses, and shifts and tricks, and denials of self-indulgences and starvings of soul might be suddenly snatched from them and leave them beggared. A shudder went through one such crowd when a young man came to speak to them from the steps of the bank. It was a kind of shuddering sigh, followed by loud murmurings, and here and there angry protests. The cashiers had been withdrawn from their desks and cheques could not be paid. “We are ruined already!” said a woman. “This war will take all our money! Oh, my God!”

The situation in Brussels wasn’t so calm, according to Hugh Gibson, the young secretary of the American Embassy:

“People in general are frantic with fear, and are trampling each other in the rush to get money out of banks…” Across Europe shopkeepers refused to take paper money, rightly fearing inflation, and would accept only gold or silver coins in payment. Gibbs wrote: “It was strange how in a day all gold disappeared from Paris… At another place where I put down a gold piece the waiter seized it as though it were a rare and wonderful thing, and then gave me all my change in paper, made up of new five franc notes issued by the Government.”

The impending conflict wrought havoc on the plans of tourists across the continent. Edith Wharton, who happened to be in Paris, remembered the strange atmosphere of August 1:

The next day the army of midsummer travel was immobilized to let the other army move. No more wild rushes to the station, no more bribing of concierges, vain quests for invisible cabs, haggard hours of waiting in the queue at Cook’s [a travel agency]. No train stirred except to carry soldiers, and the civilians… could only creep back through the hot streets to their hotel and wait. Back they went, disappointed yet half-relieved, to the resounding emptiness of porterless halls, waiterless restaurants, motionless lifts: to the queer disjointed life of fashionable hotels suddenly reduced to the intimacies and make-shift of a Latin Quarter pension. Meanwhile it was strange to watch the gradual paralysis of the city. As the motors, taxis, cabs and vans had vanished from the streets, so the lively little steamers had left the Seine. The canal-boats too were gone, or lay motionless: loading and unloading had ceased. Every great architectural opening framed an emptiness; all the endless avenues stretched away to desert distances. In the parks and gardens no one raked the paths or trimmed the borders. The fountains slept in their basins, the worried sparrows fluttered unfed, and vague dogs, shaken out of their daily habits, roamed unquietly, looking for familiar eyes.

Declarations of Neutrality, Italy Opts Out

With war imminent, Europe’s smaller nations went running for cover, beginning with Bulgaria. They declared neutrality on July 29 (although the following day it accepted a huge loan from Germany, foreshadowing its later intervention on the side of the Central Powers). The Netherlands declared its neutrality on July 30, followed by Denmark and Norway on August 1, while Switzerland mobilized to protect its own longstanding neutrality. Greece declared its neutrality on August 2, and Romania followed suit on August 3.

Among the Great Powers, besides Britain, only Italy remained undecided. While a member of the defensive Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, Italy was actually hostile to her supposed ally Austria-Hungary, with Italian nationalists coveting Austria’s ethnic Italian territories of Trentino and Trieste as the final, missing pieces of a united Italy. Italy also had a secret non-aggression pact with France, and a close relationship with Britain, which controlled the Mediterranean and provided most of Italy’s coal imports.

So it was hardly surprising when Italy’s Council of Ministers voted for neutrality late on the evening of July 31, announcing the news to Italian newspapers shortly after midnight. It seemed to surprise to Germany and Austria-Hungary, who were victims of their own wishful thinking. As late as July 31, German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg was asking Italy to join them in the coming war, and on August 1 the Austrian chief of the general staff, Conrad, wrote to his Italian counterpart Cadorna, asking how many Italian divisions they could count on during the war.

But Germany and Austria-Hungary now paid the price for Vienna’s repeated refusals to offer Italy suitable incentives, in the form of Trentino and Trieste, to take their side in a European war. In fact, within a year Italy would join their enemies after Britain and France came up with their own attractive offer.

France Mobilizes

Following the German declaration of “imminent danger of war,” warning of impending mobilization, and the insulting ultimatum on July 31, on the morning of August 1, the chief of the general staff Joseph Joffre informed War Minister Adolphe Messimy that he would resign unless the cabinet agreed to mobilization by no later than 4 p.m. that day. Joffre then attended the cabinet meeting at 9 a.m. to present his arguments in person.

President Poincaré recalled, “Joffre appeared with the placid face of a calm, resolute man whose only fear is lest France, outstripped by German mobilization, the most rapid of all of them, might speedily find herself in an irreparable state of inferiority.” After explaining his reasons and warning that Germany was already calling up reservists and requisitioning horses, even before ordering mobilization, Messimy recalled, “There was no protest, no comment.”

A few hours later, at 11 a.m., Premier Viviani presented his perfectly uninformative answer to the German ambassador, Schoen, while the French cabinet was further emboldened by the good news that Italy would remain neutral, freeing up French forces which would have otherwise been tied down guarding the frontier with Italy. Finally, around noon, the cabinet agreed to order mobilization, taking effect at 4 p.m. that day.

Credit: Clasgallery

Germany Mobilizes, Declares War on Russia

Coincidentally, Germany and France declared mobilization within minutes of each other (Germany’s time zone is an hour ahead of France). War Minister Falkenhayn recalled:

As up to 4 p.m. there has been no reply from Russia although the ultimatum expired at midday, I drove to the Chancellor’s to get him to go with me to see the Kaiser and ask for the promulgation of the mobilization order. After considerable resistance he consented and we rang up Moltke and Tirpitz. Meanwhile His Majesty himself rang and asked us to bring along the mobilization order. At 5 o’clock in the afternoon the signing of the order by His Majesty on the table made from timbers of Nelson’s “Victory” [a British gift]. As he signed I said: “God bless Your Majesty and your arms, God protect the beloved Fatherland.” The Kaiser gave me a long hand shake and we both had tears in our eyes.

Credit: Telegraph

After the mobilization order was signed, ambassador Pourtalès in St. Petersburg presented the German declaration of war to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov, who recalled:

Count Pourtalès came to see met at 7 o’clock in the evening and after the very first words asked me whether the Russian government was ready to give a favorable answer to the ultimatum presented the day before. I answered in the negative, observing that although general mobilization could not be cancelled, Russia was disposed, as before, to continue negotiations with a view to a peaceful settlement. Count Pourtalès was much agitated. He repeated his question, dwelling on the serious consequences which our refusal to comply with the German request would involve. I gave the same answer. Pulling out of his pocket a folded sheet of paper, the Ambassador repeated his question for a third time in a voice that trembled. I said I could give no other answer. Deeply move, the Ambassador said to me, speaking with difficulty: “In that case my Government charges me to give you the following note.” And with a shaking hand Pourtalès handed me the Declaration of War… After handing the note to me, the Ambassador, who had evidently found it a great strain to carry out his orders, lost all self control and leaning against a window burst into tears. With a gesture of despair he repeated: “Who could have thought that I should be leaving St. Petersburg under such circumstances!” In spite of my own emotion… I felt sincerely sorry for him. We embraced each other and with tottering steps he walked out of the room.

Credit: Chronicling America

Ordinary Russians were less sympathetic, and that night an angry mob looted and burned the German embassy in St. Petersburg. Sergei Kournakoff, a Russian cavalry officer (and future Soviet agent in the U.S.) recalled the scene:

I could see flashlights and torches moving inside, flitting to the upper storeys. A big window opened and spat a great portrait of the Kaiser at the crowd below. When it reached the cobblestones, there was just about enough left to start a good bonfire. A rosewood grand piano followed, exploded like a bomb; the moan of the broken strings vibrated in the air for a second and was drowned: too many people were trying to outshout their own terror of the future… A young woman tore her dress at the collar, fell on her knees with a shriek, and pressed her naked breasts against the dusty boots of a young officer in campaign uniform. “Take me! Right here, before these people! Poor boy… you will give your life… for God… for the Tsar… for Russia!” Another shriek, and she fainted.

Back in Berlin on the evening of August 1, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg received the opaque French response to the previous day’s ultimatum and began drawing up a declaration of war against France. German troops were moving to occupy small, neutral Luxembourg, a critical rail hub for the invasion of Belgium and northern France. But the day was to see one more bizarre twist—a final flip-flop by the mercurial German Kaiser, which brought chief of the general staff Moltke to the point of nervous collapse.

A Final Bid to Keep Britain Out

Germany was now grasping at straws in its effort to keep Britain from intervening. The Germans knew that Britain had made some kind of defensive commitment to France, although the terms remained secret, and they were also aware that, despite their best efforts to paint France and Russia as the aggressors, the invasion of Belgium could easily trigger a hostile British response. Therefore, at this late stage the best—indeed, only—chance of keeping Britain out was to somehow get France to remain neutral as well.

This was obviously a long shot, given the Franco-Russian Alliance, but on August 1, Berlin seized on a message from Ambassador Lichnowsky in London, reporting that one of Grey’s subordinates, William Tyrell, said a new idea was being discussed in the cabinet, to the effect “that if we were not to attack France, England would remain neutral and guarantee the passivity of France… Tyrell urged me to use my influence so that our troops should not violate the French frontier. He said everything depended on this.”

In other words, according to Tyrell, Britain might somehow persuade France to abandon Russia, meaning Germany didn’t have to invade France, which in turn meant Britain could stay out of the war. It’s not clear exactly where this highly improbable idea originated, and Lichnowsky should never have communicated it as a firm proposal, since Tyrell mentioned it in passing. But Kaiser Wilhelm II jumped at the offer, suddenly ordering Moltke to call off the invasion of France and instead prepare to transfer all Germany’s forces to focus exclusively on Russia.

This insane command meant completely abandoning the Schlieffen Plan and improvising the movements of millions of men, countless horses and artillery pieces, and thousands of tons of tons of supplies across Germany to the Russian frontier. In other words, it was completely impossible, and on hearing the capricious order, Moltke had a nervous breakdown: “I thought my heart would break… I was absolutely broken and shed tears of despair. When the telegram… was submitted to me, repeating the order… I slammed down the pen on the desk and said I would not sign.”

In typical fashion, this order would itself soon be reversed, as it became clear that Lichnowsky’s report had been inaccurate. After Kaiser Wilhelm II telegraphed King George V about the supposed offer, the British monarch politely replied, “In answer to your telegram just received I think there must be some misunderstanding as to a suggestion that passed in friendly conversation between Prince Lichnowsky and Sir Edward Grey this afternoon when they were discussing how actual fighting between German and French armies might be avoided.” Britain was not in a position to guarantee French neutrality and the Kaiser ordered Moltke, now a quivering wreck, to proceed with the invasion of Belgium after all.

Meanwhile, the tide of British public opinion was already turning against Germany. Beginning on July 30, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had been communicating with the leaders of the Unionist opposition, so-called because they bitterly opposed Irish independence, instead supporting the “Union” of Britain and Ireland. Just a week before the conservative Unionists had been battling the Liberal cabinet, which supported Irish home rule, but now key figures including Bonar Law and Edward Carson let it be known that they were willing to put aside these internal disagreements for the time being and support British intervention on the side of France and Belgium.

The support of the Unionists gave the Liberal “hawks,” including Prime Minister Asquith, Foreign Secretary Grey, and Churchill himself, crucial political leverage over their anti-interventionist colleagues in the Liberal cabinet. With support from one of the main opposition groups, they might be able to reform a new cabinet without the anti-interventionists—which of course made the anti-interventionists more likely to reconsider their own stance. At last the way was clear for British intervention in the coming conflict.

See the previous installment or all entries.