The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in August, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 107th installment in the series.

March 10-11, 1914: Mixed Messages from Italy

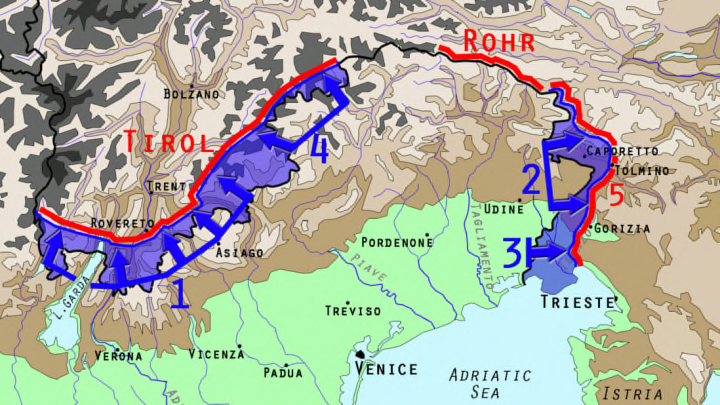

In the opening months of the Great War, Germany and Austria-Hungary were enraged by the failure of their supposed ally Italy to come to their aid, compounded by an even greater betrayal when the Italians sided with their enemies and attacked Austria-Hungary in May 1915 (shown above). Public opinion excoriated the “treacherous Latins” for this “stab in the back,” but as always the truth was more complicated.

Italy first joined Germany and Austria-Hungary in the defensive Triple Alliance in 1882, mostly out of fear of France, which had invaded Italy under Francis I, Louis XIV, and Napoleon Bonaparte; annexed Corsica in 1768; stationed troops in Rome and annexed Italian-speaking Savoy and Nice under Napoleon III; and more recently opposed Italy’s colonial ambitions in North Africa. But when France renounced new territorial claims and formed a closer relationship with Italy’s friend Britain, Italian motives for adhering to the Alliance faded.

Italy also had unfinished business with her “ally” Austria-Hungary, which held Italian-speaking territory around Trent and Trieste. The heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, cherished hopes of recovering Lombardy and Venice, lost to the new Italian state in 1859 and 1866, and Italian nationalists deplored Austria-Hungary’s oppression of its Italian minority, especially the recent Hohenlohe Decrees banning Italians from public office in August 1913. Italy and Austria-Hungary were also competing for influence in the Balkans.

In short, many Italians considered Austria-Hungary the real enemy, prompting Italian diplomats to hedge their bets. In 1902, Italy and France signed a secret non-aggression pact as well as a colonial agreement for North Africa, assigning Libya to Italy and Morocco to France. The Italians also insisted on adding a clause to the Triple Alliance treaty specifying that Italy would never have to fight Britain. And in 1909, Italy struck a deal with Russia aiming to preserve the status quo in the Balkans, which was obviously directed against Austria-Hungary.

But in typical fashion, Italian diplomats mostly kept their military colleagues in the dark about these other agreements, since none technically involved new military commitments. As far as Italian generals were concerned, Italy’s main obligations were still to its Triple Alliance partners. Thus in March 1914, the chief of the Italian general staff, Albert Pollio, dispatched General Luigi Zuccari, the commander of Italy’s Third Army, to Berlin to hammer out plans for military cooperation in the event of a hypothetical French attack on Germany.

At a conference on March 10 and 11, 1914, Zuccari and the German quartermaster general, Major General Count George von Waldersee, agreed on a war plan calling for the transportation of three Italian army corps and two cavalry divisions through Austria to the Rhine, where they would reinforce German troops facing the French invaders. Meanwhile Italy would attack France directly across their shared frontier, forcing the French to divert troops from the main attack on Germany. In return (although the generals didn’t discuss this), Italy could probably expect territorial rewards in Nice, Savoy, Corsica, North Africa, and the Balkans.

This plan was so radically at odds with Italy’s actual actions just a few months later, it’s tempting to conclude it must be evidence of Italian duplicity. But Pollio, the conservative chief of the general staff, was a staunch supporter of the Triple Alliance, and Zuccari was simply following his orders. Again, as professional soldiers they didn’t consider diplomacy their concern: The fact that Italy’s civilian government was more likely to go to war against Austria-Hungary than for her was irrelevant to their duty as officers.

Events were about to reveal the basic dysfunction in the Triple Alliance. As Austria-Hungary and Germany pushed for war in July 1914, Italian diplomats correctly pointed out that the treaty was defensive in character, and therefore didn’t apply if Austria-Hungary provoked a broader conflict by attacking Serbia. Austria-Hungary also neglected to consult Italy before delivering the fatal ultimatum to Serbia (in July 1913 the Italian foreign minister, San Giuliano, had warned Austria-Hungary not to embark on any Balkan adventures without consulting Italy first, so there was no excuse for keeping Italy out of the loop one year later). Finally, in July 1914, Austria-Hungary also seemed to be breaking its promise to give Italy “compensation” for any territorial gains Austria-Hungary might make in the Balkans.

In other words, despite the public outcry in Germany and Austria-Hungary over Italian “treachery,” the fact was Italy had absolutely no obligation to join their war under the defensive Triple Alliance treaty—and beneath all their feigned indignation, top officials in Berlin and Vienna knew it. On March 13, 1914, the chief of the German general staff, Helmut von Moltke, advised his Austrian counterpart, Conrad von Hötzendorf: “At present… we must begin the war as if the Italians were not to be expected at all.”

See the previous installment or all entries.