Museums often have millions of items in their collections, so it’s not surprising that things occasionally get misidentified or even lost—but it must be a nice surprise to rediscover them. Here are just a few examples of specimens and artifacts that were lost, then found, in museums.

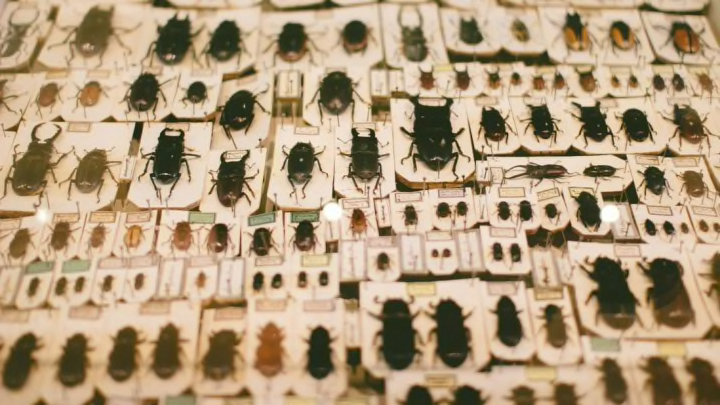

1. Beetles Collected by David Livingstone

In October 2014, while he was searching the collections of London's Natural History Museum, Max Barclay found a wooden box with 20 beetles pinned inside and labeled “Zambezi coll. by Dr. Livingstone.” That would be Dr. David Livingstone, who collected the insects during his Zambezi expedition of 1858–64, the first European venture to reach and explore Lake Malawi in Africa. Barclay, the museum's collections manager of Coleoptera and Hymenoptera, said the beetle hoard “includes almost 10 million specimens, assembled over centuries ... I have worked here for more than 10 years and it was a complete surprise and incredibly exciting to find these well-preserved beetles, brought back from Africa 150 years ago almost to the day.”

The beetles were among a collection of 15,000 insects left to the museum by lawyer and amateur entomologist Edward Young Western when he died in 1924; he may have acquired the specimens from one of the members of the expedition at a natural history auction in the 1860s. Although the specimens were technically the property of the government, they were never published, so selling them quietly would have been relatively easy.

The specimens aren’t just a cool find; they also have scientific value. Researchers at the museum can use the historical specimens “to study the effect of changing environments on plants and animals around the world,” Barclay said.

2. A 6500-Year-Old Human Skeleton

Janet Monge, curator-in-charge of the physical anthropology section of the Penn Museum in Philadelphia, had always known about the mystery skeleton, which sat in a wooden box in basement storage. It had been at the museum as long as she had been. But no one understood its significance until this 2014, when researchers were working to digitize records from Sir Leonard Woolley’s 1929-30 excavation at the site of Ur in southern Iraq.

William Hafford, Ur digitization project manager, and his team found records indicating which unearthed objects went to which museums after Woolley's dig. According to a press release, half of the artifacts stayed in the newly formed nation of Iraq, and the other half was split between the two museums that had sponsored the excavation, the British Museum and the Penn Museum. Among a number of items on the list were “one tray of ‘mud of the flood’ and ‘two skeletons,’” the press release notes. “Further research into the museum's object record database indicated that one of those skeletons, 31-17-404, deemed ‘pre-flood’ and found in a stretched position, was recorded as ‘not accounted for’ as of 1990.”

Woolley’s field notes contained photos of the archaeologist “removing an Ubaid skeleton intact, covering it in wax, bolstering it on a piece of wood, and lifting it out using a burlap sling,” according to the museum. Monge told Hafford that she had no records of a skeleton like that, but did have a mystery skeleton in a box—and after the box was opened it was clear that the 6500-year-old skeleton was the one unearthed during Woolley’s excavation.

Scientists have named the skeleton—which once belonged to a muscular middle-aged man standing 5 feet 8 inches to 5 feet 10 inches—Noah, because he lived after a great flood that had covered southern Iraq.

3. Barnacles from Charles Darwin

In the decade before he published On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin corresponded with Japetus Steenstrup, then head of the Royal Natural History Museum in Denmark (the precursor to the current Natural History Museum’s Zoological Museum), who lent Darwin some fossilized barnacles in November 1849 for his Species research. “It is a noble collection, & I feel most grateful to you for having entrusted them to me,” Darwin wrote Steenstrup when he received the box of barnacles in January 1850. “I will take great care of your specimens.” (According to the History Blog, when the packages were late, Darwin was so concerned that he actually put an ad in the paper offering a reward for their return.)

When she was studying the correspondence between the two scientists, Hanne Strager, the head of exhibitions at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, noticed in the correspondence that Darwin mentioned a list of 77 additional barnacles he had sent as a gift when returned the borrowed barnacles to Steenstrup in 1854. That list was found in Steenstrup’s papers, and the museum was able to locate 55 of the barnacles, with the original labels—not an easy task, because they had not been kept together. As the History Blog notes, there wasn’t a reason to keep them together: “On the Origin of Species was five years away. The barnacles were seen as specimens like any other, not the curated collection of a great pioneering scientist. They were spread throughout the museum collection according to their species.” The museum has since put the specimens on display. Most of the missing barnacles come from one genus, and were probably lent out to another institution or scientist who never returned them.

A number of Darwin specimens have been lost and then rediscovered, including a beetle he found on an expedition to Argentina (which was named Darwinilus sedarisi in the scientist’s honor 180 years later); the taxidermied remains of a tortoise he captured in the Galapagos and kept as a pet; and a Tinamou bird egg he collected during the HMS Beagle expedition.

4. The Earliest Tyrannosaurid

This exceptionally well-preserved fossil, found in Gloucestershire, England, during an excavation in 1910, ended up in the collections of the Natural History Museum of London in 1942. It was misclassified for a number of years—its discoverers thought it was a new species of Megalosaurus—but eventually it was recognized as an unknown genus and dubbed Proceratosaurus. In 2009, scientists used computed tomography scans to determine that the dino is the oldest known relative of the Tyrannosauridae. It lived around 165 million years ago.

"If you look at [Proceratosaurus] in detail, it has the same kinds of windows in the side of the skull for increasing the jaw muscles," Angela Milner, associate keeper of paleontology at the Natural History Museum, told the BBC. "It has the same kinds of teeth—particularly at the front of the jaws. They're small teeth and almost banana-shaped, which are just the kind of teeth T. rex has. Inside the skull, which we were able to look at using CT scanning, there are lots of internal air spaces. Tyrannosaurus had those as well."

"This is a unique specimen,” Milner said. “It is the only one of its kind known in the world."

5. A Long-Beaked Echidna

Up until last year, scientists believed that the endangered, egg-laying long-beaked echidna had last lived in Australia 11,000 years ago—until the Natural History Museum in London found a specimen from their collections. According to its tag, the echidna was collected in Australia in 1901; the handwriting belonged to naturalist John Tunney, who visited North West Australia to collect specimens for Lord Walter Rothschild’s private collection (Rothschild apparently kept common echidnas, among other exotic animals, as pets).

The only known population of long-beaked echidnas live in the forests of New Guinea, but this discovery might mean that the creature isn’t extinct in Australia at all, and is still living undetected in some remote part of the continent. The region where Tunney collected this specimen is still so hard to reach that to get to parts of it requires a helicopter. Scientists plan to look for the long-beaked echidnas. "Finding a species that we … [thought] was extinct for thousands of years and still alive, that would be the best news ever,” Roberto Portela Miguez, curator of the mammals department at the Natural History Museum in London, told iTV.

6. Alfred Russel Wallace's Butterflies

Interns are routinely saddled with less-than-desirable projects, and on the surface, Athena Martin appeared to be one of those interns: During a four-week internship at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, the 17-year-old’s assignment was to go through 3340 drawers of butterflies searching for specimens collected by Alfred Russel Wallace, a Victorian naturalist who came up with the idea of evolution and natural selection independently of Darwin. The museum knew that there were specimens of Wallace’s in its collection, but didn’t know which specimens were his, or what species he had collected.

Martin’s task was not an easy one—it required her to read the tiny, handwritten labels pinned beside each insect—but it paid off: The intern discovered 300 of Wallace’s specimens, including a Dismorphia, which Wallace collected in the Amazon from 1848-52. It’s a particularly exciting find because his boat caught on fire during the return journey and most of the specimens were lost at sea. “I was a bit confused when I first found the Amazon specimen,” Martin said in a press release, “because I thought there might have been a labeling error due to the unusual location in comparison to the other specimens I was finding. It wasn't until I showed the specimen to [my supervisor James Hogan] that I found out that it was from the Amazon.”

The butterflies weren’t the only Wallace specimen lost and then found: In 2011, Daniele Cicuzza of the Cambridge University Herbarium found fern specimens—33 species in 22 genera and 17 families—that Wallace had collected on Gunung Muan Mountain in Borneo.

7. A Bear Claw Necklace from the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Sometimes, doing an inventory of what’s in storage can be very interesting, as two collections assistants at Harvard’s Peabody Museum found out in 2003. The duo was photographing artifacts in the Oceania storerooms when they came upon a grizzly bear claw necklace in excellent condition. They soon realized that the necklace had been incorrectly identified—it wasn’t Oceanic at all. Further research revealed that the necklace came from the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806, and was one of just seven surviving Native American artifacts that were definitely brought back by the explorers. It had been missing since it was cataloged in 1899.

The primary purpose of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark's two-year journey from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean was to map the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase, but they also studied the area’s plant and animal life and tried to establish relations with Native American tribes. It was perhaps in one of those meetings that they received the bear claw necklace, which was probably given to the explorers by a chief. "Bear claw necklaces, which relate to the bravery and stature of warriors, were treasured by Indian people,” Gaylord Torrence, curator of Native American art at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, said in a press release. “They are rare from any time period. The newly discovered bear claw necklace acquired by Lewis and Clark is quite probably the earliest surviving example in the world."

The necklace—which contains 38 bear claws—had a convoluted path to the Peabody. After the expedition, it was donated to the Peale Museum in Philadelphia; when the Peale closed in 1848, the necklace went to the Boston Museum, owned by the Kimball family. When that museum suffered fire damage in 1899, 1400 objects from its collection went to the Peabody Museum at Harvard, including the bear claw necklace. However, the Kimball family apparently changed its mind and decided to keep the necklace, even though the Peabody had already cataloged it. A Kimball descendant donated the necklace to the Peabody in 1941, and a staff member mistakenly cataloged it as an artifact from the South Pacific Islands.

8. Insect Fossils from the Jurassic

In the 1800s, geologist Charles Moore excavated hundreds fossils from sites in the southwest of England, including a quarry called Strawberry Bank near Ilminster. Most of Moore’s collection—which contained as many as 4000 specimens—was bought by the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution (BRLSI) in 1915, 34 years after the geologist’s death. But part of the collection was given away to the Museum of Somerset (then the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society), where it was put in storage and forgotten for almost a century. In 2011, these specimens—which includes insect fossils dating back to the Jurassic—were rediscovered when the BRLSI received a grant to restore Moore’s fossils. "These packages haven't been unwrapped since 1915 and some are in wrappings dating back to 1867, so it's quite exciting to unwrap them for the first time,” Matt Williams, collections manager at the BRLSI, told the BBC. “Amongst them I have been discovering unknown Strawberry Bank specimens.”

9. A Juvenile Human's Mandible

In 2002, scientists in the department of anthropology at the Field Museum of Natural History were reorganizing the European archeological collections when they found a juvenile mandible, which had come from Solutré, an Upper Paleolithic site that was excavated beginning in 1866. This particular specimen, unearthed in 1896, had somehow not been noticed, but in 2003, the pieces were analyzed, and according to a paper published in Paleo, “The specimen is comprised of approximately 60 percent of a juvenile mandible, broken post-mortem into two fragments … The resulting age range for this individual is 6.7-9.4 years, with an average of 8.3 years.” Radiocarbon dating revealed that the mandible was much more recent in origin than the ground in which it was found; it dates to 240 AD and 540 AD. In the paper, the scientists write that it’s safe to assume “the human mandible, no. 215505, represents a much later burial which intruded into bona fide Upper Paleolithic strata. … While this result lessens the significance of the individual specimen, it does begins to offer some insight into the nature and stratigraphy of the archaeological levels of Solutré as is represented in collections at the Field Museum of Natural History.”

10. An Emperor Penguin

Photographs taken of the University of Dundee’s D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum when it first opened in the early 1900s show a beautiful emperor penguin specimen on display. The bird made it through the demolition of the old museum in the 1950s, then disappeared. It turned up in the ‘70s, when it served as the mascot for the Dundee University Biology Society. The penguin got lugged around on nights out and even propped up the bar at one of the students’ regular drinking destinations. Eventually, those late nights and bar-prop duties took their toll: The hard-partying penguin’s condition deteriorated, and in the ‘80s, it was sent off to a natural history museum to be restored. And then it disappeared again.

The bird wasn’t found for another three decades, when it turned up in The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum collection in April 2014. “We have finally been able to have the planned conservation work carried out and our penguin is looking as good as new in its new home in the D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum,” Matthew Jarron, curator of museum services at the university, said in a press release. The bird was promptly put back on display.

11. A Tlingit War Helmet

In 2013, staffers at the Springfield Science Museum in Massachusetts were selecting objects for a new exhibition called “People of the Northwest Coast" when curator of anthropology Ellen Savulis came across a very interesting artifact. Described in records as an "Aleutian hat," it was ornately carved from a single piece of dense wood. None of the information she could find about hats made by Aleutians matched the object she was studying. So she called Steve Henrikson, curator of collections at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, to ask him about it. When he viewed images, Henrikson knew that it was a war helmet made by the Tlingit people of southwest Alaska. Based on its decoration, he deduced that it was likely made in the mid-19th century or earlier.

The helmet entered the museum collection sometime after 1899 and was labeled "Aleutian hat," and was entered into the museum's collection records under that name. Forty years later, it received a permanent collection number, then sat in museum storage until Savulis discovered it. "It’s very rare," Henrikson said in a press release about the discovery. "There are less than 100 Tlingit war helmets in existence that we know of. I’ve been studying them for over 20 years and I’m sure I’ve seen most of them.”