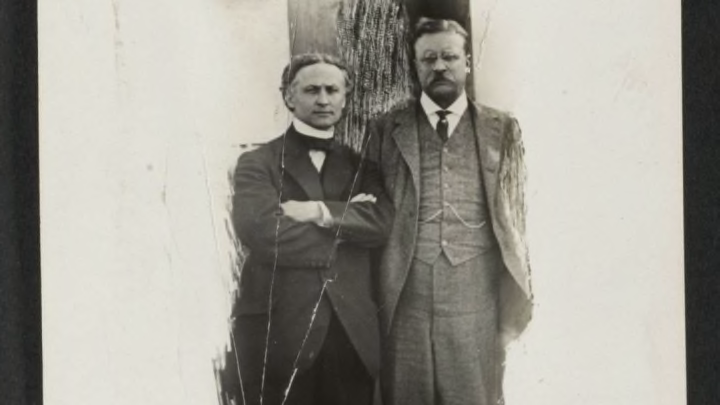

When the SS Imperator set sail for New York City in June 1914, it had on board bigwigs of both politics and entertainment—namely, former president Theodore Roosevelt and acclaimed illusionist Harry Houdini. Houdini was returning from a performance tour across the UK, and Roosevelt had been busy with a tour of his own: visiting European museums, meeting ambassadors, and then attending the wedding of his son, Kermit, in Madrid. Though the two men hadn’t crossed paths before, they soon became fast friends, often exercising together in the morning (at least, whenever Houdini wasn’t seasick).

The ocean liner hadn’t booked Houdini to perform, but when an officer asked Houdini if he’d give an impromptu performance at a benefit concert on the ship, he agreed, partially at the insistence of his new companion.

Little did Roosevelt know, Houdini had spent weeks plotting an elaborate ruse especially for him.

Houdini Hatches a Plan

Earlier in June, when Houdini was picking up his tickets for the trip, the teller divulged that he wouldn’t be the only celebrity on the SS Imperator.

“Teddy Roosevelt is on the boat,” the teller whispered, “but don’t tell anyone.”

Houdini, knowing there was a good chance he’d end up hosting a spur-of-the-moment show, started scheming immediately. The story was recounted in full in a 1929 newspaper article by Harold Kellock, which allegedly used Houdini’s own words from unreleased autobiographical excerpts.

Having heard that The Telegraph would soon publish details about Roosevelt’s recent rip-roaring expedition through South America, Houdini paid his editorial friends a surprise visit.

"I jumped into a taxi and went to The Telegraph office to see what I could pick up," he said. They readily obliged his request for information, and even handed over a map of Roosevelt’s journey along the Amazon.

What followed was a combination of spectacular cunning and good old-fashioned luck.

Houdini hatched a plan to hold a séance, during which he would employ a particular slate trick common among mediums at the time. In it, a participant jots down a question on a piece of paper and slips it between two blank slates, where spirits then “write” the answer and the performer reveals it.

He prepared the slates so that one bore the map of Roosevelt’s entire trail down Brazil’s River of Doubt, along with an arrow and the words “Near the Andes.” In London, Houdini had also acquired old letters from W.T. Stead, a British editor (and spiritualist) who had perished on the RMS Titanic in 1912. Houdini forged Stead’s signature on the slate to suggest that the spirit of Stead knew all about Roosevelt’s unpublicized escapades.

Upon boarding the ship, Houdini faced only two obstacles. First, he had to finagle his way into performing a public séance with Roosevelt in attendance. Second, he would have to ensure that the question his “spirit” answered was “Where was I last Christmas?” or something very similar.

Houdini cleared the first hurdle with flying colors, saying he “found it easy to work the Colonel into a state of mind so that the suggestion of séance would come from him.” Though the master manipulator doesn’t elaborate on what exactly he said about spiritualism during their conversation—later in his career, Houdini would actually make a name for himself as an anti-spiritualist by debunking popular mediums—it sufficiently piqued Roosevelt’s interest. When the ship’s officer requested that Houdini perform, Roosevelt apparently goaded, “Go ahead, Houdini, give us a little séance.”

Just like that, Houdini had scheduled a séance that Roosevelt wouldn’t likely miss—and the illusionist wasn’t going to leave a single detail up to chance.

A Back-Up Plan (Or Two)

Rather than bank on the shaky possibility that Roosevelt himself would pen the perfect question, Houdini prepared to stuff the ballot, so to speak. He had copied the question "Where was I last Christmas?" onto several sheets of paper, sealed them in envelopes, and planned to make sure that only his own envelopes ended up in the hat from which he’d choose a question. (It seems like a problematic plan, considering the possibility that Roosevelt would speak up to say something like "Wait, that wasn't my question," but Houdini doesn't clarify how he hoped this would play out.)

The morning of the séance, Houdini devised yet another back-up plan. With a razor blade, he sliced open the binding of two books, slipped a sheet of carbon paper and white paper beneath each cover, and resealed them.

As long as Roosevelt used one of the books as a flat surface to write on, the carbon paper would transfer his question to the white sheet below it—meaning that even after Roosevelt had sealed his question in an envelope, Houdini could sneak a glance and alter his performance accordingly.

A Little Hocus Pocus

That night, Houdini kicked off the show with a series of card tricks, where he let Roosevelt choose the cards. “I was amazed at the way he watched every one of the misdirection moves as I manipulated the cards,” he said, according to Kellock’s article. “It was difficult to baffle him.”

Then, it was time for the séance.

"La-dies and gen-tle-men," Houdini proclaimed. "I am sure that many among you have had experiences with mediums who have been able to facilitate the answering of your personal questions by departed spirits, these answers being mysteriously produced on slates. As we all know, mediums do their work in the darkened séance room, but tonight, for the first time anywhere, I propose to conduct a spiritualistic slate test in the full glare of the light."

Houdini distributed the slips of paper, gave instructions, and then solicitously passed Roosevelt one of the books when he saw him start to use his hand as a surface. As Roosevelt began to write, composer Victor Herbert, also in attendance, offered a few shrewd words of caution.

"Turn around. Don't let him see it," Houdini heard him warn Roosevelt. "He will read the question by the movements of the top of the pencil."

"The Colonel then faced abruptly away from me and scribbled his question in such a position that I could not see him do it," Houdini said, adding, "Of course that made no difference to me."

After Roosevelt finished, Houdini took the book and slyly extracted the paper from the inside cover while returning it to the table.

In an almost unbelievable stroke of luck, Roosevelt’s question read “Where was I last Christmas?” Houdini wouldn’t need to slip one of his own envelopes between the slates after all.

"Knowing what was in the Colonel's envelope, I did not have to resort to sleight of hand, but boldly asked him to place his question between the slates himself," Houdini said. "While I pretended to show all four faces of the two slates, by manipulation I showed only three."

Then, after Roosevelt stated his question aloud to the audience, Houdini revealed the marked-up map, bearing the answer to Roosevelt’s question signed by the ghost of W.T. Stead.

In a 1926 article from The New York Times, Houdini describes Roosevelt as “dumbfounded” by the act.

“Is it really spirit writing?” he asked.

“Yes,” Houdini responded with a wink.

In Kellock’s account, however, Houdini confessed that “it was just hocus-pocus.”

Either way, it seems that Houdini never explained to Roosevelt exactly how he had duped him, and Roosevelt died in 1919, a decade before Kellock’s detailed exposition hit newsstands.

To fully appreciate the success of Houdini’s charade, you have to understand just how difficult it would’ve been to pull one over on a sharp-witted guy like Theodore Roosevelt. Dive into his life and legacy in the first season of our new podcast, History Vs. podcast, hosted by Mental Floss editor-in-chief Erin McCarthy.