It’s estimated that more than $4 billion in bets (most of them illegal) take place on Super Bowl Sunday, but putting money on the game itself isn’t the only way to make a fortune on football. According to one very unscientific economic theory, the winner of the big game could predict the success of the U.S. stock market that year.

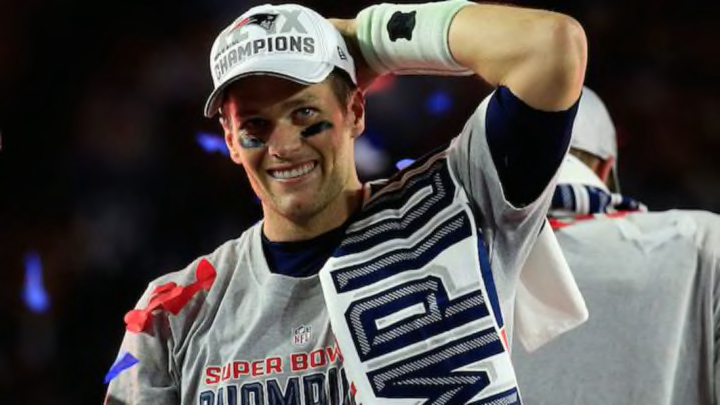

The theory is known as the "Super Bowl Indicator," and it has some simple rules: If an original NFL team (now known as the NFC, or National Football Conference) wins the Super Bowl, that year will be a bull market, meaning the stock market will be up. If a team descended from the AFL (now the AFC, or American Football Conference) wins, it’ll be a bear market, meaning the stock market will fall for the year (as if most of America needs more reason to despise the New England Patriots's '00s and '10s AFC Super Bowl dynasty). The rules get a little more confusing when it comes to post-merger expansion teams like the Tampa Bay Buccaneers—most people leave them in whichever conference they're a part of, while some uniformly lump them in under the AFC/AFL bear market rules.

The AFL and NFL were at one point rival football leagues before merging in 1970. Now just known as the National Football League, the entire league was split into two conferences: the NFC and the AFC. While certain teams have changed conferences over the years—like the Pittsburgh Steelers, who began in the old NFL but are now an AFC staple—the indicator applies to where a team originated (again, with some exception for expansion teams). In fact, the predictor is never wrong for the Steel City: the stock market rose all six years that Pittsburgh won the Super Bowl.

The trend was first noticed in 1989 by the late Leonard Koppett, a sports writer for The New York Times, who thought it up as a joke with fellow writers. At that point, the theory was right 10 of 11 times: "Every year since the Super Bowl was first played in 1967, at least one of the three indices has upheld the formula," Koppett wrote. "Each, individually, has been right 20 of 22 times, or 91 percent of the time. All three have been correct, moving in unison 18 times, or 82 percent of the time."

Its accuracy ever since has been so impressive that even Wall Street has taken notice. Since the inaugural championship game, the indicator has been spot-on in 40 of the past 50 Super Bowls, for an 80 percent success rate.

The offhand observation of Koppett caught the attention of financial advisor Robert H. Stovall, who now acts as the unofficial custodian of the indicator in the world of Wall Street. Stovall knows the whole thing is nothing but superstition, but he reasons: "There is no intellectual backing for this sort of thing except that it works." When Stovall, a veteran in the financial world, would give speeches on investments, he would often be besieged by investors asking questions about the Super Bowl Indicator, saying "that’s what they want to know about."

Investors have a long history with superstitions. Some believe the country that builds the tallest skyscraper is due for a market collapse. Others think the entire month of October is cursed, since that's when markets crashed in 1929, 1987, and 2008. Perhaps most bizarrely, there's also a trend known as the "SI Swimsuit Indicator," which suggests that the U.S. stock market fares better when an American model graces the cover of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, rather than a foreign-born model.

So what does the indicator say about Super Bowl LI? If the theory is right, an Atlanta Falcons win would mean stocks will rise, while a New England Patriots victory should (once again) get investors prepared for a down 2017.