In the early part of the 20th century, visitors to W.P. Penniman’s combination mortuary and furniture store in Enid, Oklahoma, could spend time with some unusual company. Sitting in one of the rooms was a man dressed in a business shirt, vest, and slacks. Tufts of hair sprouted from his head; a wispy mustache covered his upper lip, which one observer wrote “resembled a scrub brush used many times too often.” His skin was the color and consistency of wax paper. An open newspaper rested on his lap.

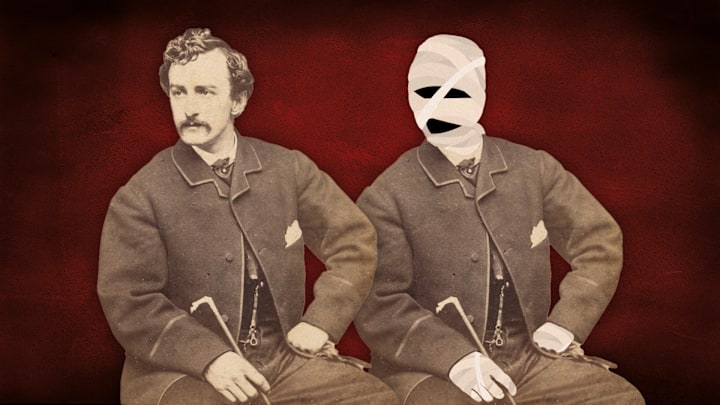

This person was dead and embalmed, though that wasn’t the most remarkable thing about him. If some people were to be believed, the ossified corpse was that of actor and assassin John Wilkes Booth.

Never mind that Booth had died nearly 40 years previously, or that he had been buried in a family plot in Baltimore. In 1903 Oklahoma, Penniman’s strange curio was said to be evidence that Booth had eluded authorities after assassinating Abraham Lincoln, had gone on the lam for decades, and had confessed his true identity on several occasions, culminating in his death by suicide and subsequent preservation. Soon, the mummy known as “John” or “Old John” would become a national touring attraction for carnivals and sideshows, inviting great debate over whether his improbable backstory could possibly be true.

One man in particular had become obsessed with the possibility and would soon claim “John” for himself. He was Finis Bates, a respected lawyer, ardent Booth conspiracy theorist, and the grandfather of Matlock and Misery star Kathy Bates.

The Faux Booth

The circumstances of Lincoln’s assassination have been well-documented. On April 14, 1865, a radicalized theater performer named John Wilkes Booth shot the president in the back of the head while he was attending a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Lincoln died 10 hours later; Booth spent 12 days evading capture before being cornered by Union soldiers in a barn located near Bowling Green, Virginia. The barn went up in flames; in the chaos, Booth was shot and killed by Thomas “Boston” Corbett. Authorities promptly had him buried; they wouldn’t turn the remains over to the Booth family until 1869. At the government’s insistence, the Booths placed their infamous member in an unmarked grave to avoid any future commotion or desecration.

These seemingly undisputed facts would become relevant some three years later, when a young lawyer named Finis Bates was settling down in Texas. While representing a client in a dispute over a liquor license, he visited a local saloon owner named John St. Helen. The man might have been able to help his client’s case, but he told Bates he was reluctant to ever testify in court. St. Helen, he said, was not his real name.

You Might Also Like ...

- 9 Popular Quotes Commonly Misattributed to Abe Lincoln

- When Abraham Lincoln Tried His Hand at Being a True-Crime Writer

- 17 Facts About Conspiracy Theories

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Despite this red flag, Bates struck up a friendship with St. Helen and became his legal representative. Then, in 1877, St. Helen fell ill. Speaking to his friend Bates with what he thought were his dying words, he made a startling admission.

“My name is John Wilkes Booth, and I am the assassin of President Lincoln,” St. Helen said.

St. Helen wanted Bates to inform Edwin Booth, his purported brother, of his demise. But soon St. Helen was on the mend, leaving both men in the awkward position of having to grapple with a deathbed confession without the death. St. Helen went on to explain that he had actually avoided the showdown with Union soldiers in Virginia and that they had shot the wrong man—an accomplice of Booth’s named Ruddy who had aided in his escape. Because Ruddy was carrying some of Booth's personal effects, including a check and letters, it led the lawmen to assume they had gotten the right person.

St. Helen said he had subsequently moved around from place to place, adopting different names and somewhat safe in the knowledge that the government likely would never admit they had allowed America’s most wanted man slip through their fingers.

Bates was incredulous. At this stage, he considered St. Helen to be a purveyor of tall tales. Even so, the two maintained their friendship through 1878, at which point both men left Texas and lost touch with one another. Bates understood St. Helen was moving to Colorado, while he was headed for Memphis, Tennessee.

In the years that followed, Bates couldn’t shake St. Helen’s confession from his mind. Though he later became busy as the assistant district attorney for Shelby County, he spent his free time researching Booth’s shooting and began to note discrepancies. No one in Booth’s family was called upon to identify Booth’s corpse in the days following his death, for example. Others reported that the man shot at the Virginia barn had red hair—but Booth had black hair. Most notably, Dr. Frederick May, a surgeon who had once operated on Booth’s neck to remove a tumor and who examined the body, noticed that the corpse had an injured right leg, though it was presumed that Booth’s left had been fractured in his leap from the balcony after shooting Lincoln. (Dr. May did note the surgical site on the neck matched, and he was ultimately confident he was looking at the body of Booth.)

Whether Bates was objective in his assessment or whether he was prioritizing facts favoring the theory Booth was alive is open to interpretation. But in January 1903, some 25 years after last seeing St. Helen, Bates received a telegram. Someone in Enid, Oklahoma, had just made another deathbed confession about being John Wilkes Booth. And he had a letter addressed to Bates in his possession.

When Bates arrived in Enid, he was escorted to the store of W.P. Penniman, the town’s mortician and furniture dealer. (Such macabre hybrid businesses weren’t unusual for the era.) Bates was shown the body of a man known to people in Enid as David E. George, a house painter said to be overly fond of alcohol and morphine.

Bates was shocked. There was no doubt in his mind the man known as David George was John St. Helen. Therefore, David George was John Wilkes Booth.

The Mummy

Bates soon learned that David George had made a similar confession to the proprietors of a hotel where he had been staying—twice, actually. He insisted he was Booth shortly after making an attempt on his own life and again when he deliberately ingested arsenic, the latter killing him.

Unlike the confession to Bates, which the lawyer had mostly kept to himself, the Enid confessions were leaked to press and caused a minor stir. Bates went so far as to inquire with Booth’s nephew Junius Booth III, who believed George could have been his uncle, though he had actually never met him; so, too, did two of Booth’s onetime theater colleagues. It was decided that it would be best to embalm George in the event authorities wanted to take a closer look at these claims or potentially try to scrutinize his corpse for physical evidence.

The media didn’t wait for any such confirmation. “If press dispatches from Enid … are to be relied upon, it has been established beyond a doubt that John Wilkes Booth, the murderer of President Lincoln, escaped death at the time the crime was committed,” wrote The Logan Republican.

Bates returned to Memphis, newly motivated to continue his pursuit of the truth; George remained in Enid, where his embalmed remains were kept as a curiosity for Penniman’s business. Though local laws didn’t permit the public exhibition of a decedent, Penniman was amenable to showing him to visitors who expressed an interest. The body also attracted kids who dared one another to sprint into the shop to get a look at Lincoln's alleged killer. He was dressed in a suit, his two glass eyes vacantly perusing a newspaper. Other reports of the time describe George propped upright or in a coffin-type wooden box. He remained a presence at Penniman’s for years.

“After embalming, the body has been exposed to the air and has turned a dark brown, almost black and resembles the Egyptian mummies except that it is not wrapped in cloths as all these of the East,” one reporter wrote in 1905. “It stands erect on a cross piece beside a chimney in a corner of the work room ghastly and grinning and is not at all pleasant to look upon.”

Bates, meanwhile, worked feverishly to finish a book on the subject, which he published in 1907 with the sensational title The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth. It was an exhaustive chronicle of what could have happened had Booth escaped, including St. Helen’s explanation of why he had killed Lincoln. (It was, according to Bates, a plot concocted by Vice President Andrew Johnson to assume the presidency.) The entire tome, Bates wrote, was “for the correction of history.”

But Bates was not content to leave it at that. At some point after 1915, he actually acquired George’s mummy from Penniman, who was getting out of the mortuary-and-furniture-store business. (Automaker Henry Ford was reputed to be interested in the body, too, but his own hired investigators couldn’t corroborate the story.) Some reported Bates was able to exercise a legal maneuver in which he, as St. Helen’s onetime lawyer, could conceivably be executor of his estate, including his mummified remains; it’s also possible Bates simply bought it, or that Penniman just wanted to be relieved of the macabre prop. In any event, George was shipped to Bates in Memphis.

Initially, Bates seemed content to keep George on his property, possibly in anticipation of one day conclusively proving he was Booth and therefore being entitled to the $100,000 government reward for Booth’s “capture.” But in 1921, a newspaper story reported that the mummy was being displayed for the public in Los Angeles, complete with his Booth backstory. While it doesn’t explicitly state Bates loaned or rented George out, it’s likely that’s what happened.

It would be a case of foreshadowing. After decades at Penniman’s and with Bates, the purported mummy of Booth was about to go on tour.

The Evidence

When Bates died in 1923, his widow had little use for the brittle corpse that had taken up residence in their parlor (and later their garage). By 1928, she found a willing buyer in William Evans, a sideshow and carnival promoter who figured there was money to be made in the salacious exhibition of the mummy, who came to be known in sideshow circles as “John.” Evans paid $1000 for him, then proceeded to charge 25 cents for the privilege of being in the same room as Lincoln’s killer.

Evans, already trampling on the boundaries of good taste, was not exactly respectful of the dead: He sometimes dragged “John” to social dances, where he would be propped up in the middle of the dance floor as a conversation piece.

Evans eventually got out of the mummy business, selling “John” at a profit to another sideshow promoter, Joseph Harkin, around 1930. One report had Harkin paying as much as $12,000, or the equivalent of $232,000 today. He, too, proceeded to take “John” around the country, hoping to draw the morbid gawking of customers. (Already, other promoters had boasted of various random human skulls, all of them fraudulently claiming to have once belonged to Booth.)

By this point, “John” was displayed rather ignominiously in a wooden box, naked save for a pair of khaki shorts. Someone had cut a flap in his back, permitting people to peer into his embalmed innards. Caretakers applied liberal amounts of petroleum jelly to try and keep him moisturized.

The mummy’s appeal was largely based on Bates’s work and perhaps some willful suspension of disbelief. Then, in 1931, a Chicago physician named Orlando Scott was recruited by the Chicago Press Club with a proposal. He and a group of colleagues would be permitted to examine “John” to see if they could comment on the validity of the claim that he was indeed Booth.

Their findings were good news for the sideshow. Scott announced that some of the physical abnormalities of the mummy were consistent with what was known about Booth. The assassin had injured his left leg while fleeing the theater after shooting Lincoln, a fact consistent with the slightly shortened left leg of the corpse—a sign it might have once fractured. (Though it’s worth noting that Bates wrote St. Helen had demonstrated to him an injured right leg while he was still alive.) “John” also sported a deformed right thumb, the type of injury Booth sustained as a child. He had a neck scar consistent with Booth’s neck operation to remove a tumor. A scar over his right eyebrow matched one suffered by Booth.

“We have four coincidences,” Scott wrote. “Taken separately, none would be unusual. Taken two at a time, they would be possible. But taken all together, it taxes credulity to believe this mummy is not that of John Wilkes Booth.”

Scott’s most peculiar finding came when he took x-rays of the mummy. Inside his stomach was a piece of jewelry—a ring—that had a faint trace of the letter B on it. Scott theorized the B was for “Booth.” But no sufficient explanation for why Booth would swallow it or why it would remain in his stomach without being excreted was forthcoming.

But Scott did have an idea of why the whole thing had happened in the first place. “I am convinced the primary reason why purported identification was made of a body as Booth was to allay the terrific public clamor which undoubtedly would have resulted in the renewal of hostilities between the North and the South,” Scott wrote. In other words, the faux Booth shot in the barn needed to remain Booth, lest another Civil War break out.

Despite Scott’s endorsement, both Evans and Harkin were dispirited by a simple truth: The George mummy was not the sensational attraction it was expected to be. No massive crowds turned out. Some, in fact, reportedly stayed away from sideshows featuring the corpse, finding its presence unsettling. (Harkin had no such reservations: At night, he and his wife slept in the same railroad car that toted the mummy around.) At least once, he was fined for transporting a corpse without the proper paperwork.

Harkin eventually sold “John” to Jay Gould, owner of Jay Gould’s Million Dollar Spectacle, in 1937. Gould continued touring it, though as public interest waned, so did close attention to its whereabouts. Media mentions grew faint through the 1950s and 1960s, all but drying up by the 1970s.

In 1977, Gould’s son, Dr. George Gould, told the Akron Beacon Journal that he might have a partial share of ownership in the mummy. In Dr. Gould’s telling, Harkin, who was touring with Gould’s show, had up and disappeared with it one night. The senior Gould told his son he knew the mummy’s whereabouts and could likely lay claim to it, but wasn’t interested in pursuing the matter. If he was the legal owner, then it would belong to his heirs: the elder Gould died in 1967. But Dr. Gould had no idea of the mummy's location.

If “John” persists in corporeal form, no one seems to know where he is.

An Enduring Enigma

As mentioned, Bates is the grandfather of Kathy Bates, the Oscar-winning actress perhaps best known for her role as Annie Wilkes in 1990’s Stephen King adaptation Misery. Her family’s history with the George mummy (whom she knew as “Uncle John”) has made for interesting talk show fodder, though Bates never met Finis. (She was born in 1948, 25 years after his death.)

Could “John” really be Booth? When Booth was moved to the Baltimore's Green Mount Cemetery in 1869, family members, including Booth’s mother, positively identified the body as that of their infamous relative. In 1913, following the minor furor surrounding Bates’s book, Baltimore mayor William Pegram offered a sworn statement that Booth’s body had been delivered there and that he had personally seen it. When the mummy grew popular, a caretaker apprentice, Henry Mears, said the body was definitely Booth’s, whom he had known personally. Any other explanation was, in his estimation, “all nonsense.”

The truly compelling aspect of the mummy’s story, if Dr. Scott is to be believed, is that it shares similar physical characteristics to Booth. But that 1931 exam seemed to miss the fact that Booth had his initials tattooed on his hand; George did not. (Whether any sworn affidavit exists of Dr. Scott’s findings is also a contentious topic.) It’s certainly possible Booth would want to scrub the incriminating “JWB” off his skin if he wished to continue living as a free man. Still, the mummy’s distinguishing features don’t appear to be convincing enough to contradict the word of Booth’s family, caretakers, and others who saw his body with their own eyes in Baltimore.

One certain way to tell would be to exhume the remains in the Booth family plot and test it for DNA or look for those trademark characteristics, though attempts by the Booth family descendants to do so in the past have been rejected by the cemetery and the courts. It’s also unlikely time has been kind to what’s left of the remains, with acidic soil potentially rendering them unworkable for study. Yet it's hardly any more prudent to rely on the word of carnival barkers and even Bates himself, all of whom had a financial interest in promoting the George-as-Booth theory. (Bates’s book reportedly sold a robust 70,000 copies.)

“John” is not likely a presidential assassin. But if he were, it would be somewhat fitting that his corpse was trotted around as a public spectacle. Following his fatal encounter with Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s own embalmed body went on a three-week railroad tour across the country.