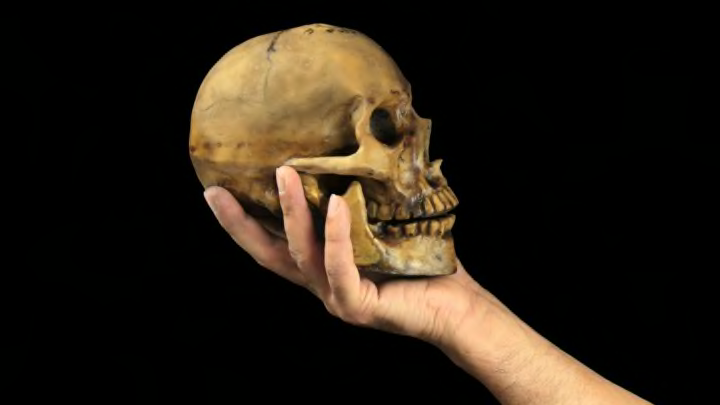

Even if showcasing your grandfather’s skull on your living room mantle is the type of offbeat tribute he absolutely would have loved, your chances of making it happen are basically zilch. Mortician Caitlin Doughty explains exactly why in her new book Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions From Tiny Mortals About Death, excerpted by The Atlantic.

Having written permission from dear old Gramps stating that you are allowed to—and, in fact, should—display his skull after his death simply isn’t enough, for two reasons. First of all, most funeral homes lack the equipment required to decapitate a corpse and thoroughly de-flesh the skull. Doughty admits that she doesn’t even know what that process would entail, though her best guess for a proper cleaning involves dermestid beetles, which museums and forensic labs often use to “delicately eat the dead flesh off a skeleton without destroying the bones.” Unfortunately, the average funeral home doesn’t keep flesh-eating beetles on retainer.

The second hindrance to your macabre mantle statement piece is a legal matter. In order to maintain respect for the dead, abuse-of-corpse laws prevent funeral homes from handing over corpses or bones, but the terms differ widely from state to state. Kentucky’s law, for example, prohibits using a corpse in any way that would “outrage ordinary family sensibilities,” but leaves it entirely open to interpretation how an “ordinary family” would behave.

Sometimes, of course, it’s relatively obvious. Doughty recounts the case of Julia Pastrana, who suffered from hypertrichosis, a condition that caused hair growth all over her face and body. Her husband had her corpse taxidermied and displayed it in freak shows during the 19th century as a money-making scheme—a clear example of corpse abuse. Since the laws are so ambiguous, however, funeral professionals err on the side of caution.

Funeral homes also must submit a burial-and-transit permit for each body so the state has a record of where that body went, and the usual options are burial, cremation, or donation to science. “There is no ‘cut off the head, de-flesh it, preserve the skull, and then cremate the rest of the body’ option,” Doughty says. “Nothing even close.”

If you’re thinking the laws sound vague enough that it’s worth a shot, law professor and human-remains law expert Tanya Marsh might convince you otherwise. As she told Doughty, “I will argue with you all day long that it isn’t legal in any state in the United States to reduce a human head to a skull.”

The laws about buying or selling human remains also vary by state, and are “vague, confusing, and enforced at random,” according to Doughty. Many privately sold bones come from India and China, and, though eBay has banned the sale of human remains, there are other ways of procuring a stranger's skull online “if you are willing to engage in some suspect internet commerce,” Doughty says.

[h/t The Atlantic]