Gunpei Yokoi couldn’t stop staring at the stranger.

It was the late 1970s, and Yokoi was commuting to his job at Nintendo, the Japan-based amusements company that was years away from becoming synonymous with electronic games. Riding the train, Yokoi observed a fellow passenger punching buttons on his handheld calculator, deriving some sort of improvised pleasure from doing calculations.

It was a scene that was replayed over and over during Yokoi’s train rides. In those moments, Yokoi later recalled, he was struck by the idea of a portable game system—one that could be operated not just by kids, but by adults. The idea was radical, especially in Japan, where a serious work ethic was the order of the day. The notion of an adult wasting time by playing games was a social taboo.

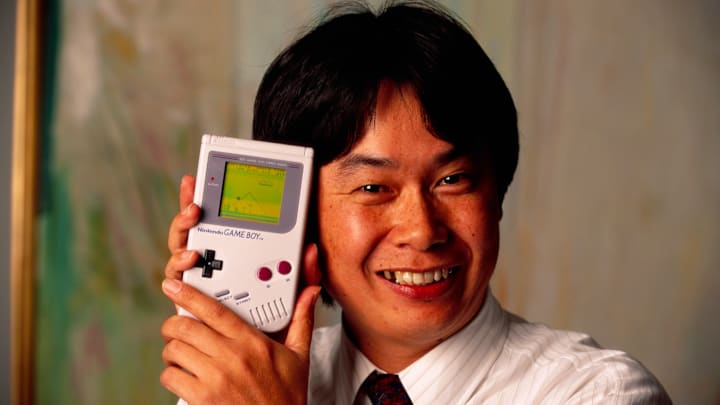

Over a decade later, Yokoi’s seed of an idea would grow into Nintendo’s Game Boy, a deceptively simplistic device that proved Nintendo could stretch beyond its 8-bit console system. The Game Boy also settled a longstanding debate over whether video games were strictly child’s play.

Giving Nintendo a Hand

Yokoi joined Nintendo in 1965, back when the company was still known primarily for playing cards. Starting as an assembly line supervisor, Yokoi climbed the ranks thanks to successful products like the Ultra Hand, a mechanical appendage, and the Love Tester, a novelty machine that attempted to quantify emotional responses in couples who were holding hands.

Yokoi’s biggest hit, and the one that would help chart Nintendo’s course in the future, was the Game & Watch, a portable electronic gaming device introduced in 1980. Each Game & Watch, which came in different colors, played a pre-loaded game on an LCD screen (later versions had two screens) with a clock in the corner. It was not dissimilar to Mattel Football, a 1977 handheld sports game that had proven to be a hit in the U.S. When the Game & Watch was released in the States in 1982, it drew favorable comparisons with handheld electronics like Sony’s Walkman. Lighter, portable devices were the new consumer preference.

But the Game & Watch wasn’t the company’s only video game product. In the early 1980s, both Nintendo and Yokoi were focused on the Family Computer, or Famicom, a video game console that plugged into televisions. The sound and graphics were vastly superior to the Atari 2600, which had dominated the market before excess inventory and a rash of subpar games had sunk home gaming. Released in Japan in 1983 and in the U.S. in 1985, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) helped revive what was perceived to be a dead or dying industry.

But Yokoi was still interested in portable gaming. With Nintendo developer Satoru Okada and his research and development team, Yokoi plowed ahead on a device that would prove to be a vastly improved successor to the Game & Watch: Instead of a single title, the device would be able to accept an endless number of game cartridges. Dubbed the Game Boy, it was roughly the size of a calculator, but chunkier, with a green-gray dot matrix monochrome screen manufactured by Sharp.

The latter feature wasn’t due to any hardware restrictions. “The technology was there to do color,” Yokoi said later in a 1997 interview translated by gaming history website Shmuplations. “But I wanted us to do black and white anyway. If you draw two circles on a blackboard, and say ‘that’s a snowman,’ everyone who sees it will sense the white color of the snow, and everyone will intuitively recognize it’s a snowman. That’s because we live in a world of information, and when you see that drawing of the snowman, the mind knows this color has to be white … Once you start playing the game, the colors aren’t important. You get drawn, mentally, into the world of the game.”

There was another crucial benefit to a monochrome display: It was far less voracious when it came to using batteries. Four AA batteries could last a player 10 to 14 hours, whereas a color display might eat multiple batteries far more quickly. Yokoi sensed that battery conservation would be more important to game-obsessed consumers than color, though not everyone at Nintendo agreed.

“Actually, it was difficult to get Nintendo to understand,” Yokoi said. “Partly, I used my status in the company to push them into it.” (Satoru Okada would later insist he had more to do with the Game Boy’s development than had been reported, and even pushed Yokoi into moving beyond the Game & Watch’s single-game design, though he still credited both himself and Yokoi as having co-created the device.)

As Nintendo well knew, the hardware specifications didn’t matter nearly as much as the software: Super Mario Bros. arguably had as much to do with the success of the NES as anything. And while Mario would appear on the Game Boy, the Italian plumber would be elbowed out of the way by a Russian puzzle masterpiece.

Blocking Out a Strategy

The byzantine history of Tetris is a story unto itself. Developed by Alexey Pajitnov in 1984, the game—which tasks players with moving blocks of various shapes into a uniform line before they become a jumbled mess—spread rapidly via Soviet-era Russian personal computers. But licensing the game to different systems and regions became a confusing morass; illicit cartridges were issued and rights were sold off despite a lack of authority to do so.

Nintendo finally emerged with North American rights to the game for its NES and Game Boy. For the latter, it was a hand-in-glove moment. All that mattered in Tetris was the addictive gameplay and the adrenaline rush of arranging the blocks. The monochrome screen was immaterial.

Nintendo released the Game Boy in Japan during the spring of 1989 with four games available: Super Mario Land, Alleyway, Baseball, and the mahjong game Yakuman. The company sold 200,000 units in just two weeks. That was followed by the North American debut in the fall of that year. For $90, consumers got the Game Boy, four AA batteries, and something Japanese consumers didn’t get right away: Tetris.

The release was bolstered by a tie-in promotion with Pepsi, and Nintendo expected to sell 2 million to 2.5 million Game Boys before the end of 1989. But the company had only allocated 1 million units for the U.S. market, creating shortages at the retail level. Whether the lack of hardware was Intentional or not, it only drove demand further.

But the Game Boy was being positioned as something far more than a kid’s most fervent holiday wish. Part of Nintendo’s long-term strategy was in courting adult consumers, a vastly untapped demographic that the company knew held the long-term viability of the industry in its hands.

The Game Boy, Nintendo believed, was a perfect Trojan horse. “Many adults tell us they want to play,” Nintendo vice president of marketing Peter Main said in 1990. “But they are intimidated. They want to play without being ridiculed by their sons.” The Game Boy was a perfect answer for feeling abashed about gaming, allowing adults to play in relative privacy.

Nintendo even advertised the device during airings of primetime adult series like L.A. Law and Twin Peaks. The device quickly became part of the fabric of culture. In 1991, President George Bush was photographed playing a Game Boy. In 1993, Lorena Bobbitt earned infamy for severing her abusive husband’s penis with a knife. She ran out of the house with his member in one hand—and in the other, his purloined Game Boy.

By November 1990, Nintendo estimated 48 percent of Game Boy players were adults, a market it courted with puzzle games, sports games, and even travel and language cartridges. But it wasn’t just the Game Boy. By June 1991, the company figured 50 percent of NES players were over 18.

Competition for the Game Boy arrived swiftly. Atari had its Lynx system, while Sega marketed the Game Gear. Both had superior graphics on a color screen, but it didn’t matter. Neither had Tetris. And those color screens were, in the minds of Nintendo’s executives, a disadvantage.

“It's like using the Ferrari to get to the corner grocery store,” Nintendo director of advertising Bill White said of the Atari Lynx in 1989. “We think it’s really a bit more than players want and need.” (At $170, the Lynx was also nearly twice as expensive as the Game Boy.)

By 1992, sales of Game Boy and related games and devices topped $2 billion. The success of the handheld led to countless iterations—even one in color—that would all contribute to a staggering number: nearly 120 million devices were sold. It also led to the ill-fated Virtual Boy, a dizzying virtual reality offering that failed to ignite any enthusiasm.

Yokoi departed Nintendo in 1996. Sadly, he would pass away after being struck by a car in 1997. But his contributions to gaming are almost without peer: Despite its name, the Game Boy helped cement gaming as an all-ages activity.

Read More About Nintendo: