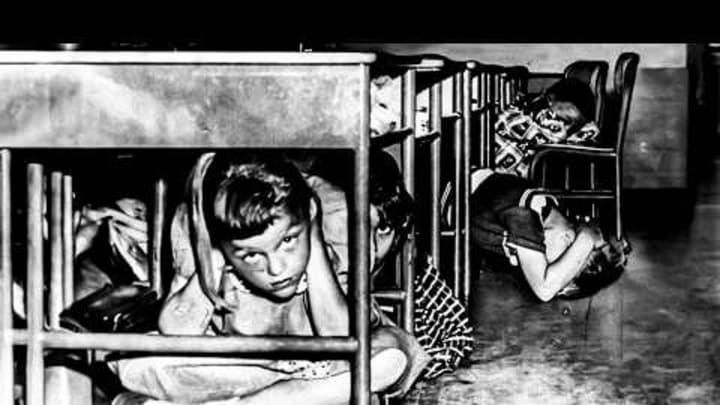

Just 1.8 seconds. That’s how long it took for students of teacher Lillian McDonald’s second and third grade classes to obey McDonald’s single command (“cover”) during a drill at Phelps School in Springfield, Missouri, in October 1962. In less than 2 seconds, the children had crawled under their wooden desks and clasped their hands around their heads. It happened so quickly that a news photographer present for the drill was afraid he had missed his shot.

In the 1950s and into the 1960s, grade school students across the country practiced some form of “duck and cover,” a civil defense strategy intended to shield children from being mortally wounded from the immediate effects of a nuclear attack. Kids got a very grown-up lesson—often instructed by an animated turtle named Bert—in seeking shelter in the event foreign conflicts went atomic for a second time.

The morbidity of the drill has been debated ever since. So has its usefulness. “Every kid in America knew this was ridiculous,” Rick Ginsberg, dean of the University of Kansas School of Education and Human Sciences, once observed. “There was no way a desk was going to save you from the bomb. It was arguably the stupidest thing ever done in American education.”

But safety wasn’t necessarily the point.

The Class Project

For a brief period of time, the United States had been the only atomic superpower in the world: The U.S. bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in Japan might have been the greatest show of military force in modern history. But by 1949, the Soviet Union was on the map, detonating an atomic weapon that could level both the playing field and, if the Soviets so chose, American soil.

In response to the Soviet tension and the outbreak of the Korean War, President Harry Truman created the Federal Civil Defense Administration program, or FCDA, a government organization that subsidized community efforts to try and mitigate the casualties of a nuclear attack on domestic cities.

“The Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950, which I have signed today, is designed to protect life and property in the United States in case of enemy assault,” Truman said in a statement accompanying his signing of the act into law. “It affords the basic framework for preparations to minimize the effects of an attack on our civilian population, and to deal with the immediate emergency conditions which such an attack would create.”

With their vulnerable adolescent populations, schools were of particular concern. Little could be done about a direct hit to a populous area, but the FCDA figured there could at least be merit to minimizing injuries in cities that were some distance away. The point was not to avoid radiation exposure, but to prevent children from being mangled from the physical effects of such a blast.

You Might Also Like ...

• 21 Ways School Was Different a Century Ago

• The Disturbing Reason Schools Tattooed Their Students in the 1950s

• When Mr. Rogers Taught Kids About Mutually Assured Nuclear Destruction

This was especially important in schools, which in postwar America had a design that favored floor-to-ceiling windows that let in plenty of sunlight. In peacetime, it was a pleasant aesthetic choice; during the Cold War and the possibility of a strike, such windows became known as “walls of death” due to the potential for shards of glass to blow into the classroom.

The duck and cover drill was simple. At the behest of a teacher or upon hearing a formidable rumble or siren in the distance, or in the event they might see a flash, children were to dive under their desks and turtle up, putting their arms over their heads and their hands over their necks. The desks would theoretically shield them from glass or rubble blasting through classrooms.

Duck and Cover

The FCDA had a drill; now it needed a teaching tool. The agency reached out to Archer Productions, an ad agency based in New York, to produce a film reel explaining the duck and cover protocol. The “star” of the reel was Bert the Turtle, an affable animal who explained the need for the training. More importantly, he was friendly, not ominous. The objective was to warn children but not frighten them—a heady task when the topic was mutually assured destruction.

The program implored children to “duck to avoid the things flying through the air” and to “cover to keep from getting cut or even badly burned.” Duck and cover, Bert instructed, was the answer to avoiding these calamities, which the literature equated to everyday dangers like road traffic.

“You have learned to take care of yourself in many ways—to cross streets safely” one pamphlet stated. “And you know what to do in case of fire. But—the atomic bomb is a new danger. It explodes with a flash brighter than any you’ve ever seen. Things will be knocked down all over town, and, as in a big wind, they are blown through the air. You must be ready to protect yourself.”

Bert went on to appear in comic strips, newspaper ads, and other material. He was somewhat analogous to Smokey Bear, who gently but seriously warned of forest fires. But while he may have been a soothing presence for younger children, not everyone could tolerate the contrast between the Disney-esque character and Armageddon. One high schooler in White Plains, New York, reported that his class “laughed hysterically” during the cartoon.

Schools around the country practiced duck and cover, though it’s hard to ascertain their frequency. In Montgomery, Alabama, students were due to have two drills for each school in the district. Some kept students in the classroom; others practiced heading to more fortified areas, like basements. (As Bert reminded them, he had a built-in shelter thanks to his shell—kids had to go find one for themselves.)

Soon, newspapers were describing kids who were no longer playing cops and robbers but duck and cover. One child would be the air raid siren, wailing; the others would quickly look for a sturdy wall to crouch against. Teachers would sometimes decorate safe harbor areas as reading areas. Bert even had song lyrics:

“There was a turtle by the name of Bert

And Bert the Turtle was very alert!

When danger threatened, he never got hurt

He knew just what to do!

He’d duck and cover, duck and cover

He did what we must learn to do, you, and you, and you, and you!

Duck and cover!”

But not all parents were pleased.

Taking Shelter

For some adults, the idea of their children going to school and being reminded of the practical realities of nuclear war was too much. Some complained to school boards, others to newspapers. Like sex education, it was a divisive topic. (So were adult duck and cover drills, in which citizens of all ages were expected to seek shelter upon hearing a siren. One drill in Lindon, Utah, was deemed a failure when some locals ran out of their houses to figure out why the siren was blaring, a decision that would have likely meant death in a real nuclear attack.)

For complainants, Bert was trotted out. “I think seeing an excellent film like this would reassure those parents who are still afraid that we are frightening their children,” Queens superintendent Max Gewirtz told The New York Times in 1952. The reel, the Times added, showed “no explosion scenes or shots of death or destruction.”

The other emerging problem was that nuclear warfare was growing increasingly intense. In 1954, the U.S. successfully tested Castle Bravo, a thermonuclear bomb far more powerful than the atomic weapons dropped in Japan nearly a decade earlier. The radiation fallout was immense. Duck and cover, while possibly protective of blunt force trauma, offered no degree of protection against a weapon of such magnitude.

The FCDA was having another problem. Despite a call for other civil measures, the agency and the Eisenhower-led government was reluctant to fund the construction of public fallout shelters. Instead, the U.S. distributed literature on how families could build their own to try and guard against the nuclear fallout, which could stretch for hundreds of miles from the blast site.

Government advice also turned to dispersal, or evacuating struck areas. This, too, was seen as impractical. Orange County, California, dismissed that official tact in 1954, instead promoting duck and cover as the only viable alternative. Having tens of thousands trying to flee an area, county officials argued, could only make things worse. Some would likely be driving toward the blast.

Officials in Pennsylvania agreed. “We must follow the procedure of duck and cover,” state civil defense head Dr. Richard Gerstell said in 1954. “There are 10.5 million people in Pennsylvania and we might as well get used to the fact that we can’t run from this thing. We could in some cases move people out, but let’s not have any loose talk about taking to the hills. I don’t pretend for one minute that under hydrogen bomb attacks, the duck and cover procedure would cut losses in half—but it would result in the saving of some lives.”

Though the Cold War persisted—the Soviets showed off a 58-megaton bomb in 1961—duck and cover did not. By the time Mrs. McDonald was directing her students to cover in 1962, it was as much for tornado preparedness as a Soviet strike or a development in the Cuban Missile Crisis. By the 1980s, only some schools were still participating. Nuclear war was still very much on the table, but there was much less optimism that huddling under a desk or near a wall would improve one’s chances.

The FCDA’s mandate of emergency preparedness would later be replaced by FEMA, which assists in community efforts for natural disasters. Duck and cover is still taught in schools, though typically for severe weather events. Rather than desks, students are taught to assemble in hallways and away from windows.

Ultimately, duck and cover drills might have been less about physical safety than emotional reassurance. For millions of Americans, particularly children, a sense of powerlessness permeated culture during the Cold War. Having some strategy, however ineffectual it might have actually been, was better than doing nothing at all.

“When we grew up with bomb shelters and drills, we were being told that adults would take care of us,” one baby boomer said of her duck-and-cover upbringing in 1984. “Even though I was scared and worried, I also knew that somebody was doing something that might save me.”

It was certainly preferable to another atomic era program: giving children metal dog tags in the event their bodies needed to be identified. Some even bore their religious orientation for burial purposes.

Read More About the Atomic Age: