The 1920s: a period defined in the United States not only by opulence but also by a sense of deep mourning. During World War I, more than 100,000 Americans lost their lives, followed by nearly 700,000 more deaths during the 1918 flu pandemic. It was death on a scale previously unknown in the modern era, allowing for the resurgence of spiritualism. The movement supposed that our dead are still among us, as spirits, and can be communicated with under the right set of circumstances and with the right medium to channel their energy. Grief-stricken people seeking to connect with their lost loved ones helped create a booming industry, and the movement had several prominent followers—Mae West, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and Thomas Edison among them.

But the movement was not without opposition. One such skeptic was Rose Mackenberg. The stenographer-turned-private detective grew up with a healthy belief in the supernatural and even considered herself a believer—but in 1925, things shifted when she was given the case of an investor who’d lost money in stocks based on the advice of a “psychic.” To assist with the case, Mackenberg called on spiritualism's greatest foe, Harry Houdini, and got pulled into a world of intrigue, subterfuge, and chicanery that would take her all the way to Capitol Hill.

Harry Houdini’s Side Hustle

Harry Houdini is known as one of the most accomplished and celebrated escape artists of all time—but he also had another, less-known calling: unmasking frauds within the spiritualist community. While Houdini himself was indifferent (or even curious) about the possibility of the supernatural, he found through his experience that that mediums and their ilk seemed to be charlatans on the whole, preying on desperate people and taking advantage of their grief.

He also resented the way some other magicians presented themselves as possessing magical and/or psychic abilities, even going so far as to do the same tricks himself just to prove he could do it without supernatural help. For example, when Egyptian magician Rahman Bey stayed in a submerged coffin in a swimming pool for 60 minutes, citing a “cataleptic trance” for his success, Houdini stayed under for an hour and 28 minutes—no trance necessary.

By the time Mackenberg reached out to have Houdini consult on her case, he already had a team of investigators at his disposal to help him unmask so-called mediums. He was so impressed with Mackenberg’s work that he asked her to join them.

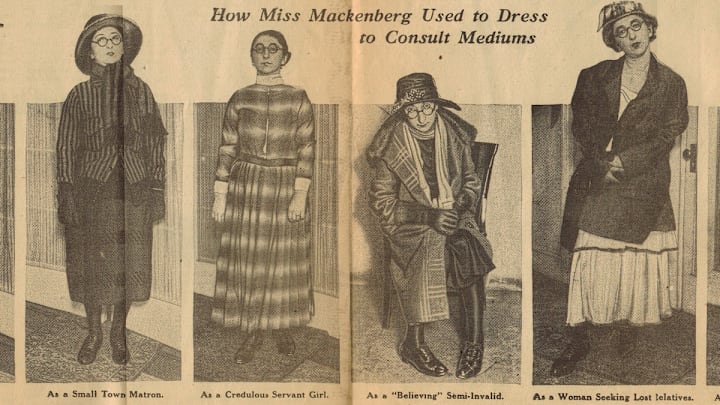

Thus began a decades-long career for Mackenberg, through which she claimed to have investigated over 1000 mediums (all, she said, frauds). She would travel to a given city ahead of Houdini’s tour and seek out spiritualists in the area, often in disguise. She’d attend a seance in costume (which was often modeled after other women she saw attending seances) using one of many aliases (one was Frances Raud, for “fraud”), and then she’d spin a yarn, often about losing a husband or child. She also became ordained by multiple spiritualist churches, earning herself a nickname in Houdini’s circle: “The Rev.”

“I never married,” Mackenberg once told The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “but I have received messages from 1000 husbands and twice as many children in the world to come. Invariably they told me they were happy where they were, which was not entirely flattering to me.”

Houdini had taught her the tricks employed by mediums in the act of deception—double exposed photographs gave the illusion of ghostly apparitions, disembodied voices created with “spirit trumpets,” table tilting, and assistants cloaked in darkness, among other tactics. She collected evidence of anything suspicious she saw or heard and reported back to the magician, who compiled everything into a dramatic debunking when he finally rolled into town. The spiritualists were often in the audience; when Houdini called them out by name and they denied his accusations, Houdini brought Mackenberg on stage to give a first-hand account.

Houdini and his team of investigators was so disliked among the spiritualist community for their unwavering dedication that it was said Houdini carried a gun, and urged Rose to do the same.

You Might Also Like ...

- 14 Fascinating Facts About the History of Magic

- When Marie and Pierre Curie Investigated a Psychic Medium

- 15 Magic Tricks You Didn’t Know You Could Do

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Spiritualism in the Capitol

Mackenberg’s most high profile case came in 1926, when she assisted Houdini in preparing to testify in Congress in support of the Copeland-Bloom bill that would ban the practice of “fortune telling” in Washington, D.C. Anyone convicted of doing so would be fined $250 (around $4500 today) or go to prison for six months.

Ahead of the hearing—and in disguise—Mackenberg visited two of the mediums set to testify against the bill. Mackenberg told the assembled lawmakers that one of the mediums had claimed that various senators had come to her for readings, an obviously scandalous revelation made even more so when Mackenberg named names. The proceedings, which took place over four days, were disorderly; the police were called on more than one occasion, there were scuffles in the hallways during breaks, and Houdini almost got punched in the face by one of the mediums’ husbands. Ultimately, the bill didn’t pass.

It was a bitter defeat for Houdini. One medium Mackenberg had visited was none other than Madame Marcia Champney, one of the magician's regular foes. Champney was a regular fixture in the late Warren G. Harding’s White House—his wife employed her services—and she later claimed that her readings played a huge role in the choices made by his administration. (It wouldn’t be the last time otherworldly forces infiltrated the White House: In 1988, Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff revealed that his boss had a secret in-house astrologer who needed to be consulted before every major decision.)

Carrying the Torch

On Halloween 1926, Houdini unexpectedly died. Mackenberg was among those close friends who received a secret code from Houdini, which he said he would use to attempt to contact them from beyond the grave if there was in fact an afterlife. Despite many mediums claiming to have reached Houdini, Mackenberg reported more than 20 years after his death that “his message has not come through.”

Mackenberg continued to lead investigations and teach others to do the same for decades, living in a “well-lit” apartment on West 24th Street in Manhattan because years of attending seances had taken their toll. “I get tired of dark rooms,” she said. Mackenberg was 75 when she died in 1968, single till the end. She and Houdini paved the way for other skeptical debunkers like James Randi and Penn & Teller, but never quite gave up hope altogether that something unexplainable was out there.