The modern spiritualist movement, which flourished in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, centered around a belief in the existence of an afterlife where the dearly departed could communicate with the living. Its popularity led to a surge in people working as psychics and mediums who claimed they could make contact with the dead and catered to high public interest in attending events like séances. That interest, however, was met with equally strong pushback from skeptics and non-believers, sometimes with heavy consequences for spiritualists who were eventually exposed as fakes. Here are 10 facts about the history of this controversial cultural phenomenon.

1. March 31, 1848 is widely considered the start of the modern spiritualist movement.

Also known as “Hydesville Day,” March 31, 1848 was the date that sisters Kate and Margaretta (or Margaret) Fox of Hydesville, New York, claimed to have contacted spirits for the first time through a “rapping” noise heard in their house. For many years, the sisters achieved fame and financial success demonstrating their “skills.” Then, in 1888, Margaret confessed that they had actually faked their act. She recanted a year later, but it was too late to salvage her reputation among other spiritualists, who despised and shunned her.

2. The movement was partly a response to the large numbers of fatalities in wars and the 1918 flu pandemic.

The period in which interest in spiritualism was at its highest also saw a number of wars that had a strong impact on America and Britain, in particular the American Civil War and, later, the First World War. The large number of men killed in battle was obviously traumatic, and people began seeking evidence of life after death as a way to comfort themselves. In the aftermath of WWI, there was further devastation when the 1918 flu pandemic began to sweep the globe, leading to an estimated 50 million deaths over the next two years. The combined effects of the First World War and the pandemic have sometimes been suggested as one of the major reasons for the revival of spiritualism during the 1920s.

3. The Society for Psychical Research was formed in London to investigate supernatural claims.

In response to the large numbers of reported cases of alleged spirit activity, as well as the rise in working mediums, the Society for Psychical Research was formed in 1882 to investigate supernatural claims with scientific rigor. Its members included major scientists and philosophers of the period, including William James (brother of novelist Henry James), John Strutt, William Crookes, Henri Bergson, and Oliver Lodge. The society conducted research via committee into phenomena like telepathy, clairvoyance, and apparitions and hauntings (there was even a Committee on Haunted Houses); investigated the credibility of reports; and exposed fraudulent behavior—although there were also occasions when the investigators concluded that they believed some cases to be legitimate.

4. The movement gave birth to the concept of ectoplasm.

Spiritualists didn’t just want to communicate with the dead—they were also eager to demonstrate physical manifestations of the supernatural. This led to the rise in interest in what became known as “ectoplasm,” a term created in the 1890s by Charles Richet.

Ectoplasm referred to physical substances supposedly produced by a medium’s body following what they claimed was a spiritual communication or other supernatural experience. Ectoplasm has never been scientifically proven to be real, however, and many examples produced by spiritualists were actually made of everyday substances like fabric or, in some cases, animal offal.

5. Thomas Edison wanted to make a spirit phone to communicate with the dead.

The great inventor Thomas Edison was one of many famous individuals who became interested in spiritualism (others included Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle and suffragist Victoria Woodhull, who was also the first woman to run for president of the United States). Edison sought to analyze spiritualism from a scientific perspective, and eventually developed a plan to create a “spirit phone” that could reach those on the other side.

“I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us,” the scientist said in an interview with Forbes. “If this is ever accomplished it will be accomplished not by any occult, mystifying, mysterious, or weird means, such as are employed by so-called mediums, but by scientific methods.”

Edison believed that the energy that went into living things existed in “swarms” that could move on to new vessels after the death of a person’s body; he also thought it was possible that these swarms could retain the memories and personalities of the deceased, and that there was the potential to make contact with them in their new realm. He even summoned friends to a gathering in 1920 to attempt such a contact with a device he had created. Edison’s spirit phone didn’t work, but he is said to have remained open to the possibility that there might be some kind of spiritual afterlife.

6. A number of famous writers joined a “Ghost Club” devoted to exploring the supernatural.

The interest in spiritualism saw the forming of social groups bringing together people who shared a fascination with the subject. One of these was the Ghost Club, which had a number of famous members, including the writers Charles Dickens, W.B. Yeats, and Siegfried Sassoon. The club still exists today.

7. It saw the rise of a new form of photography known as spirit photography.

One of the most popular aspects of the spiritualist movement was the rise of spirit photography, in which photographers claimed to have captured ghosts on film. One famous example is a photograph taken by William Mumler of Mary Todd Lincoln, widow of assassinated president Abraham Lincoln, in which Lincoln’s spirit seemed to appear in the background looking over Mary’s shoulder.

Mumler had made his name—and a lot of money—through his ability to produce photographs that seemed to show people with their deceased loved ones; his fame became so great that many, including Mrs. Lincoln, sought him out. In fact, Mumler created the ghostly effect by taking photographs on plates that had already been exposed to an earlier image. (He had originally discovered the effect by accident after taking a self-portrait on a plate that—unbeknownst to him—had already been exposed to someone else’s photograph.)

8. Some mediums who made false claims were prosecuted and imprisoned.

The level of public interest in seeing evidence of the supernatural was so high that the spiritualist movement attracted a number of con artists who saw it as an opportunity to make money—and when some were shown to be faking their claims, they were taken to court. One notable example was self-proclaimed psychic Helen Duncan, the last person in Britain to be convicted under the 1735 Witchcraft Act, which made it a crime to falsely claim to have raised spirits. She was sentenced to nine months in jail.

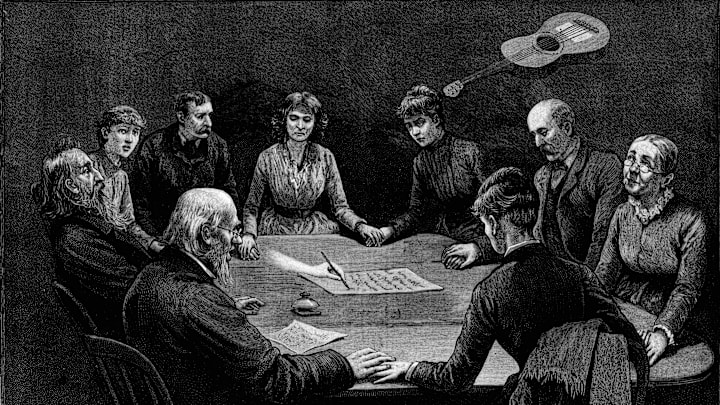

9. Stage magicians were frequent opponents of spiritualists and sought to debunk their claims.

Like spiritualism, stage magic was also popular in the Victorian era and early 20th century, but some stage magicians were very critical of the movement and sought to distinguish between their conscious illusions and spiritualist claims of authenticity. The magician Harry Houdini, who had shown an early interest in spiritualism, later turned against it—and against mediums in general, even lobbying Congress to ban fortune tellers who tried to make money from their supposed abilities. He also attended séances in order to work out how they were pulling off their stunts; one of the most famous examples came when he exposed the tricks used by medium Mina Crandon.

When Crandon applied to Scientific American to win a $2500 prize offered to a medium who could prove contact with spirits under strict observation by scientists and experts, Houdini sat in on some of her séances and even supplied a box in which she was required to demonstrate her claims. Houdini was able to identify the real sources of Crandon’s seeming psychic powers, and, after delivering his findings to the judging committee, they ultimately declined to give Crandon the award.

10. A spiritualist published a book claiming the spirit of Mark Twain had dictated it to her through a Ouija board.

Some spiritualists also claimed to have channeled the spirits of famous people through talking boards. One notorious case involved the medium Emily Grant Hutchings, who published a book in 1917 under the title Jap Herron: A Novel written from the Ouija Board, claiming Mark Twain had dictated it to her from the afterlife. Twain had actually met Hutchings and corresponded with her while he was still alive, but he was not a believer in spiritualism (which he called a “wildcat” religion) himself, and once wrote a scathingly negative account of his experience at a séance. Twain’s estate unsurprisingly sued Hutchings, and eventually she agreed to stop publishing the book.

A version of this story ran in 2022; it has been updated for 2023.