Language is ever-evolving, with new words springing up from a variety of places. Some are borrowed from other languages (“karaoke”), others are two words blended together (“doomscrolling”), and some are simply shortened (“decaf”). Given that language is a writer’s trade, it should come as no surprise that a number of new words have been born in books.

Science fiction is a particularly bountiful genre for the introduction of new words, in large part because authors come up with unique and otherworldly terms to describe their sci-fi worlds. Here are 11 common words that began life in sci-fi books, short stories, and plays.

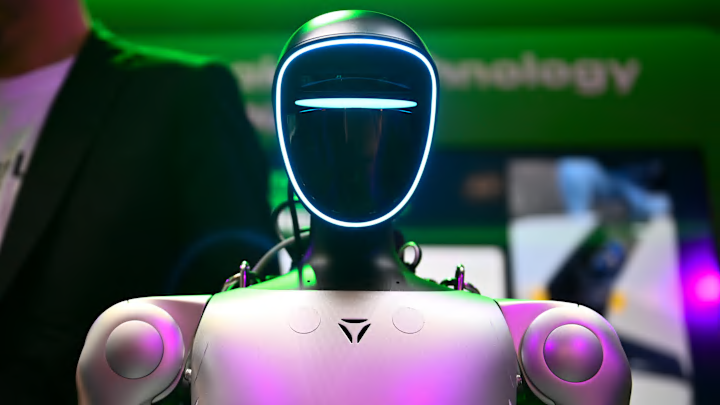

Robot and Robotics

The word “robot” can be traced back to Czech writer Karel Čapek and his sci-fi play R.U.R. (1920). The title stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, or Rossum’s Universal Robots in English. Čapek’s “roboti” is derived from the Czech word robotnik, meaning “forced worker,” and was translated into English by Paul Selver as robot in 1921. But although “robot” now usually refers to mechanical beings, Čapek’s robots were actually made of flesh and blood.

When I, Robot author Isaac Asimov then used the word “robotics” two decades later in his short story “Liar!” (1941), he simply assumed that the word was already being used by scientists, akin to linguistics and mathematics. But Asimov later found out that he had actually coined the word, being the first known person to add the –ics suffix to robot.

Cyberspace

In the early ’80s, William Gibson had an idea for a story set in what was essentially an interconnected online world, but he wasn’t sure what to name the environment. “Dataspace didn’t work, and infospace didn’t work,” he explained in a 2013 interview. He eventually settled on “cyberspace”: “It sounded like it meant something, or it might mean something, but as I stared at it in red Sharpie on a yellow legal pad, my whole delight was that I knew that it meant absolutely nothing.”

Gibson first used cyberspace in the 1982 short story “Burning Chrome” and then expanded the idea in Neuromancer (1984), which became his best-known work. His description of cyberspace in the novel was eerily prescient: “A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding...”

Astronaut

“Astronaut” is a compound of two Greek words: astro, meaning “star,” and nautēs, meaning “sailor.” The first person to put these words together was Percy Greg in his 1880 sci-fi novel Across the Zodiac, with the story’s protagonist using a spaceship called the Astronaut to journey to Mars. The first use of the word to describe a space-exploring person occurred in French in 1925. Joseph Henri Honoré Boëx (writing under the pseudonym J.-H. Rosny aîné) used the word “astronautique” in Les navigateurs de l’infini (The Navigators of Infinity), which also happens to be about a trip to Mars.

Grok

Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) follows Valentine Michael Smith, a human born and raised on Mars, as he experiences Earth for the first time. Having grown up on the Red Planet, Valentine naturally uses a few Martian words, including “grok.” In the story, this word literally translates as “to drink,” but the Martians use it to figuratively mean “understand empathically.” Fans of the novel began using “grok” themselves, and the word eventually became the name of the AI chatbot that is integrated on X.

Terraform

You might think that the idea of terraforming planets, moons, and asteroids comes from science, but the idea first cropped up in science fiction, specifically “Collision Orbit” (1942) by Jack Williamson (writing under the pen name Will Stewart). The word is a combination of Latin and English, with “terra” from the former meaning “land, earth.”

While the modern conception of the word usually involves forcibly changing the natural environment of a planet to be more Earth-like, in Williamson’s short story the process involves sustained artificial support, with the process being achieved “by sinking a shaft to [an asteroid’s] heart for the paragravity installation, generating oxygen and water from mineral oxides, releasing absorptive gases to trap the feeble heat of the far-off Sun.”

Virus

The word “virus”—as in an infection that replicates within a living host—can be traced back to the late 14th century, but the definition in terms of computing comes from Gregory Benford’s short story “The Scarred Man” (1970). In the late 1960s, Benford worked on the ARPANET project—essentially an experimental forerunner to the internet—and he foresaw the hazards of malicious programs spreading from computer to computer. He decided to write a short story about this danger and called the program VIRUS.

However, it wasn’t until 1984 that the term started being more widely used, with computer scientist Fred Cohen being credited with popularizing the definition via his paper “Computer Viruses—Theory and Experiments.”

You May Also Like:

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Metaverse

In 1992, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash introduced the word metaverse to the world. Set in a dystopian future, characters use VR headsets to connect to a universally used virtual world called the “metaverse.” Although VR headsets are now sometimes used to interact with the online world—particularly for games such as Minecraft and World of Warcraft—attempts to create a real-world expansive metaverse haven’t exactly been successful.

“I think it can exist,” Stephenson said in 2022. “Whether it should exist or will exist... those are different questions.”

As well as coining metaverse, Snow Crash also popularized the word and concept of an avatar—a graphical icon that serves as a user’s online representative. Although first used a few years earlier in 1986—in an article by Margaret Morabito about an online role-playing game created by Lucasfilm—Stephenson’s book introduced “avatar” to a wider audience, and he claims that he came up with it on his own. “It was independent ideation,” he explained.

Newspeak

George Orwell’s dystopian sci-fi novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) introduced many new words and phrases to the world. Aside from “Big Brother”—which became the name of a popular reality TV show—one of the most commonly used words from the book is “newspeak,” which is the name of the tightly controlled and deliberately limited language that is enforced in the story. Outside of the novel, “newspeak” has come to mean any speech—though particularly from those in positions of authority—that is propagandistic or deceptive in nature.

Empath

Usage of the word “empath” has shot up in recent years, with the term—which is derived from empathy—denoting a person who experiences the emotions of others to a higher degree than normal. But this word wasn’t coined by a psychologist; rather, it comes from Scottish sci-fi writer J. T. McIntosh (the pen name of James Murdoch MacGregor). In his 1956 short story “Empath,” the titular people with this ability have a supernatural power to perceive the emotions of others.

Atomic Bomb

Although the scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project were the ones to bring the atomic bomb to life in 1945, they weren’t the ones who named the deadly invention. That credit goes to H.G. Wells, who described an “atomic bomb” as a continually exploding weapon that could be dropped from planes in his 1914 novel The World Set Free.

Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, who worked on the Manhattan Project and theorized the nuclear chain reaction that led to the creation of the bomb, had read Wells’s novel. Although The World Set Free didn’t give him the scientific key to creating the bomb, it did warn him of the devastating impacts of such a weapon. “Knowing what it would mean—and I knew because I had read H.G. Wells—I did not want this patent to become public,” Szilard wrote in his memoir.