On May 15, 1941, the Hollywood Citizen-News confronted readers with the latest World War II headlines. Vichy France leader Philippe Pétain had just pledged his support to Hitler, German forces had entered Iraq, and Britain had spurned deputy Führer Rudolf Hess’s surprise (and still puzzling) attempt to broker peace.

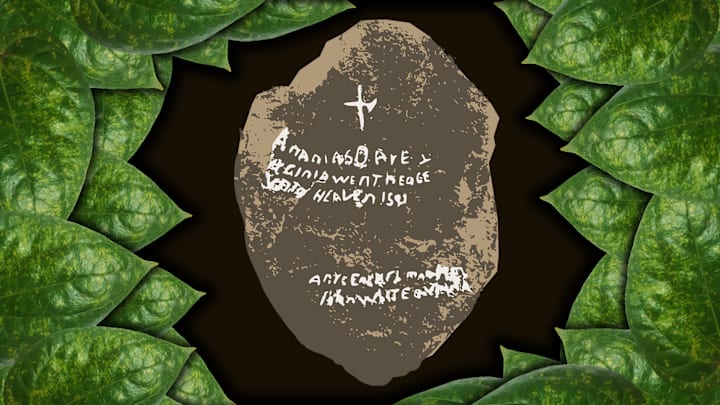

But the single image to make the front page had nothing to do with the war: It was a rock slab bearing the message that Ananias and Virginia Dare had died in 1591. Below the photo were four words that surely sent a chill through the spine of any U.S. history scholar who saw them: “‘Dare Stones’ Found Fakes.”

The Dare stones were four dozen engraved rocks unearthed in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia between 1937 and 1940. Together, they purported to answer a question that had haunted historians for centuries: What happened to the Lost Colony of Roanoke? But authenticating the artifacts was proving difficult, and now the man who’d discovered many of them had confessed that the whole thing was a hoax.

Still, the article in the Hollywood Citizen-News, written by United Press and syndicated in newspapers across the country, ended on a hopeful note: The leading researcher “said he ‘did not believe’ that all the stones were fakes.”

More than 80 years later, that hope hasn’t died.

The Gift of Slab

In November 1937, Louis Hammond of California showed up at Atlanta’s Emory University with a 21-pound rock in tow. He said he’d come across it that summer, while he and his wife were collecting hickory nuts in the woods along the Chowan River near Edenton, North Carolina. The slab—roughly 14 inches long, 10 inches wide, and 2.5 inches thick—was covered in faded etchings, which Hammond wanted Emory’s experts to decipher.

Geology professor James Lester, physics professor J. Harris Purks, history professor Haywood Jefferson Pearce Jr., and a few other faculty members succeeded in transcribing the full message. “Ananias Dare & Virginia went hence Unto Heaven 1591,” the front side read, along with a directive for any Englishman who found the rock to show it to John White.

To anyone familiar with the story of the Lost Colony of Roanoke, these names were famous. In 1587, John White and about 115 passengers had sailed from England and settled on Roanoke Island, off the coast of present-day North Carolina. White returned to England to procure some much-needed supplies mere months after their arrival, and by the time he made it back to Roanoke in 1590, all the colonists—including his daughter, Eleanor Dare; her husband, Ananias Dare; and their daughter, Virginia, the first English baby born in the New World—had disappeared, never to be heard from again.

And now, nearly 350 years later, here was an artifact signed by “EWD”—surely Eleanor White Dare—that seemingly revealed what had become of them. The flip side of the rock explained that soon after White’s departure, the party had relocated inland, where “onlie misarie & warre” befell them for two years. More than half the settlers died from disease, and Native Americans killed “al save seaven” survivors. The victims, Ananias and Virginia among them, were buried four miles east of the river, the gravesite marked with a rock bearing every name.

Huge, if true.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

So the professors strove to verify the rock’s provenance. They determined it to be quartz, which was native to the region where Hammond allegedly chanced upon it—but quartz was also common around the world. They found an Elizabethan precedent for the spelling and usage of every word but five—though, as Pearce Jr. acknowledged in a 1938 paper, “Language in the Elizabethan period was in a transition stage, and usage, from our modern viewpoint, very erratic.” They failed to recreate the inscription using modern stone-cutting techniques, and while some stonecutters thought the colonists may have been able to do it with 16th-century tools, they couldn’t say for certain.

In short, none of the professors’ efforts was conclusive, and Emory’s higher-ups, wary of being associated with a possible hoax, had more or less soured on the endeavor by spring 1938. So Pearce Jr. teamed up with his father, Haywood Pearce Sr., owner of the all-women Brenau College, to buy the stone off Hammond. The following year, after a number of fruitless searches for the aforementioned gravestone in Edenton, the Pearces tried a different tack: $500 to anyone in possession of another Dare stone.

Of all the people who came forward, a Georgia stonemason named Bill Eberhardt proved to be the most convincing—and prolific. He turned the skeptical Pearces into believers by presenting them with four stones he claimed to have found embedded in the foot of a hill near Greenville, South Carolina. Into the fourth, dated 1591, were carved 17 names, Ananias and Virginia included.

The Pearces purchased the hill and spent the summer of 1939 digging around for the colonists’ remains, which they never found. But Eberhardt continued to bring them more stones, allegedly sourced from various spots across South Carolina and Georgia; and a few other people turned up with seemingly credible stones, too. By late 1940, the collection had grown to 48 (42 of which came from Eberhardt) and painted a pretty comprehensive portrait of the colonists’ fate.

Some were gravestones—“Heyr laeth nolan Ogle & wyfe 1590 mvrthed bye salvage”—while others were messages from Eleanor to her father that detailed their dealings with Native Americans and told him in which direction they would head next. The party had apparently assimilated among Cherokee people, and Eleanor had married a chief and given birth to a daughter, Agnes, before dying in 1599.

In October 1940, Brenau College hosted a conference where historians, archaeologists, and other experts concluded that the stones did appear to be legitimate, and they couldn’t find any evidence that would definitively prove otherwise. The possibility of fraud was still on the table, but it simply seemed implausible that Eberhardt—who had only gone to school for a few years—could pull off a hoax of this magnitude, especially one that required such an intimate familiarity with Elizabethan language.

But then Boyden Sparkes started poking around.

The Snoop’s Scoop

In December 1940, Pearce Jr. sent a full account of his investigation into the Dare stones to The Saturday Evening Post, which tasked journalist Boyden Sparkes with verifying the information. After traveling all over the place and questioning all the major players—plus some scholarly sources of his own—Sparkes published an extensive report on the stones in the April 26, 1941 issue of the Post.

In it, he revealed that Eberhardt had a history of forging Native American and Mesoamerican artifacts, and pointed out that Eberhardt had been friends for years with William Bruce and Isaac Turner, who had each also “discovered” Dare stones. Sparkes also identified a number of other suspicious details in the affair.

“Eberhar[d]t had placed his first ‘find’ in South Carolina, in a line possibly 300 miles from Hammond’s ‘find’ and about 100 miles from where Eberhar[d]t lives. Yet finally he was making all his finds within four miles of his bed!” Sparkes wrote.

Other newspapers, including the Hollywood Citizen-News, picked up the story, which was incendiary, compelling, and successful in spooking Eberhardt. Days after Sparkes’s article came out, he presented Pearce Jr.’s stepmother, Lucile, with a rock engraved as follows: “Pearce and Dare Historical Hoaxes. We Dare Anything.” Not long after that, he told Lucile that he’d confess his fraud to the Post if the family didn’t fork over $200. Instead of surrendering to this pressure, Pearce Jr. took the story straight to the press. Eberhardt categorically denied the accusations, and Pearce Jr. himself doggedly clung to the belief that the trickery didn’t extend to all the stones.

“When Eberhardt brought us the first one two years ago, he had no more knowledge of Elizabethan writing than the man in the moon,” he told the press. “I do not believe that in the interim he has learned to fake them.”

But the news of Eberhardt’s alleged blackmail—coupled with Sparkes’s exposé—essentially discredited the entire operation. The authenticity of Hammond’s first stone, however, is still up for debate.

Mystery, Science, Theater

These days, all the Dare stones reside at Brenau University (which changed its name from Brenau College in 1992), and Hammond’s stone periodically finds itself at the center of a new investigation. Journalist Andrew Lawler chronicled the major attempts to solve the mystery in his 2018 book The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

In 2016, Brenau collaborated with the University of North Carolina at Asheville to slice off a bit of Hammond’s rock, which laid bare a gleaming white interior. “Whenever the original inscription was made, the white letters must have stood out sharply against the dark exterior,” Lawler wrote. A forger, he explained, “would have to age the markings so that they appeared as weathered as the stone’s natural surface. This can be done through chemicals, but that would have required considerable expertise.”

Lawler himself consulted with several scholars on the validity of the Hammond stone’s language. And though all of them pinpointed possible red flags—medieval graffiti expert Matthew Champion, for example, couldn’t locate another instance from the era of Virginia abbreviated as VIA, and Folger Shakespeare Library’s Heather Wolfe said Eleanor’s three-initial signature was non-standard—most of them felt that these details were too weak to be incontrovertible evidence of a forgery.

One notable mark against Hammond is timing. The year he found the stone, 1937, was Virginia Dare’s 350th birthday, and the Lost Colony of Roanoke was experiencing a massive resurgence in popularity. Then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt had issued a commemorative stamp for the occasion and even given a speech before a new play about the colony on Roanoke Island that summer.

“Perhaps even it is not too much to hope that documents in the old country and excavations in the new may throw some further light, however dim, on the fate of the Lost Colony and Roanoke and Virginia Dare,” he said.

According to Lawler, “None of the Emory staff recorded whether Hammond said he went to the play or knew about the president’s visit to celebrate Virginia Dare’s birthday, though it was national news at the time.” Either way, it seems a little strange that Hammond’s remarkable discovery should happen almost concurrently.

But this is yet more circumstantial evidence that does nothing to close the case on the artifact’s veracity. The Dare stone that started it all remains a mystery within a mystery.