Scientists Find Ulcer-Causing Bacteria in Ötzi the Ice Man

In 1991, hikers in the Alps found the body of a Copper Age man preserved in a glacier in the Italian Alps. That body—nicknamed “Ötzi” or “the Ice Man”—has become a rich source of information on Neolithic humans. His latest contribution comes straight from the gut: Scientists have found that Ötzi was infected with the same bacteria that causes ulcers in modern humans.

Ötzi was a survivor; that much is clear. Before he was killed by an arrow to the back about 5300 years ago, he endured parasites, degenerative conditions, and bacterial infections to live to about 45 years of age—an old man, by the standards of his time.

In the two decades since the discovery of Ötzi’s body, scientists have mapped the Ice Man’s plentiful tattoos, sampled his stomach contents to determine his last meal, and sequenced his genome. Now a team of researchers has analyzed his gut bacteria. The results of the study were published online today in the journal Science.

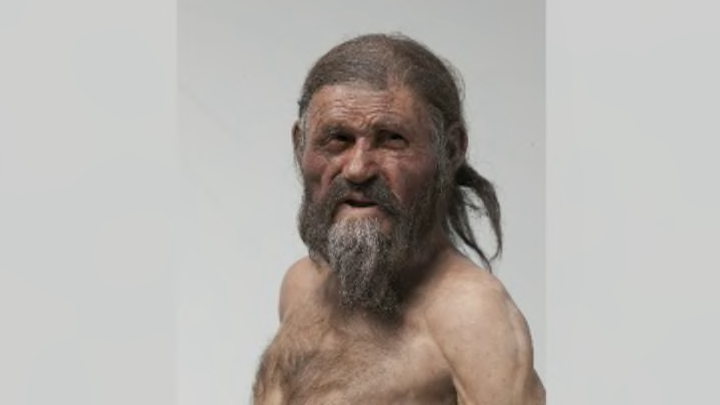

Eduard Egarter-Vigl (left) and Albert Zink (right) taking a sample from the Iceman in November 2010. Image credit: © EURAC/Marion Lafogler

“One of the first challenges was to obtain samples from the stomach without doing any damage to the mummy,” researcher Albert Zink said in a press-only teleconference yesterday. The body was kept frozen to prevent any further deterioration, so the first step was to defrost it. The researchers went in through an incision in Ötzi’s belly made during previous examinations. They took a sample of the Ice Man’s stomach contents and sequenced the DNA of everything they found. From there, they were able to spot and tease out the genomes of specific bacteria—most notably, Helicobacter pylori.

H. pylori is still around today, wreaking havoc in the guts of millions of people around the globe. The bacterium embeds in a person’s stomach lining, causing irritation that can lead to peptic ulcers and stomach cancer. The National Institutes of Health estimate that two-thirds of us are infected with H. pylori, although many people will not have symptoms.

Was Ötzi one of those people? It’s hard to say. His body was well preserved, but some parts had deteriorated over time, including his stomach lining. “He probably had some stomach issues, but we cannot really tell to what extent,” Zink said.

There are several strains of H. pylori, each originating from a different area of the globe. Because Ötzi was discovered on the border of modern-day Italy and Austria, the researchers expected to find the European strain. Instead, they found a strain that’s most commonly found in modern-day Asia, a fact that suggests humans from the two continents were already very familiar with one another.

"This mixing of two bacterial populations can only ever happen if humans actually come together, and by coming together, I mean, intimately," study co-author Yoshan Moodley said in the press conference.

Despite this infection his lactose intolerance, and his hard life, Ötzi was still going strong when he died, the researchers said.

“We think that he could have lived another 10 or 20 years if he wasn't killed by this arrow in his back,” Zink said. “So in the end, it was for sure a tough life in this time period, but with regard to this life circumstance, I think he was still in quite good shape.”