On the evening of March 3, 1993, James Perry drove from his home in Detroit toward Silver Spring, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Paying in cash, he checked into a hotel in nearby Rockville. After settling in, he took his rental car back out on the road before coming to a stop near a two-story Colonial home. Armed with a rifle, he forced his way in and shot the owner, Mildred Horn, while she stood near the foot of the stairs. Heading to the second floor, he stormed into a bedroom occupied by a nurse, Janice Saunders, who was sitting in a rocking chair. She didn’t have time to register Perry’s arrival before being shot three times in the head.

With both women dead, Perry approached a bed occupied by Mildred’s son, 8-year-old Trevor Horn. When he was 13 months old, a hospital error had left Trevor a quadriplegic with brain damage and the need for around-the-clock care. Perry removed the tube from his neck that was connected to a respirator, killing him.

Perry drove back to the hotel. It would be a year before investigators could prove he was a hired killer, and that Mildred’s estranged spouse, Lawrence Horn, had hired him.

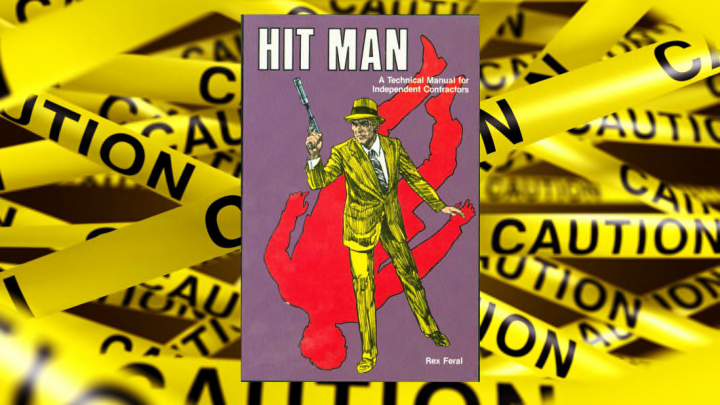

Horn, however, was not Perry’s only accused accomplice. In a case that would test the limits of the First Amendment, the families of the victims claimed Perry received his morbid education in contract killing courtesy of a book from Boulder, Colorado-based publisher Paladin Press: Hit Man: A Technical Manual for Independent Contractors. All 130 pages, lawyers argued, aided and abetted Perry in his crimes.

Paladin was a boutique publisher founded in 1970 by Vietnam veteran Peder Lund. Originally known as Panther Publications, the company changed names to avoid confusion with the Black Panthers activist group. Lund’s imprint specialized in the kind of weekend-warrior reading bookmarked by Soldier of Fortune subscribers: Titles on how to obtain fake identification, make bombs, or mount guerrilla warfare were popular sellers. They were in business less than two years before the FBI began keeping a file on them.

Handling most of their transactions via mail order gave Lund few opportunities to see his customers face-to-face. While most would be what his legal team would later describe as “Walter Mitty types,” fetishizing the clichés of action heroes, some may have absorbed the material—like instructionals on how to make a firearm silencer—without irony.

Paladin originally published Hit Man in 1983. Written by an unknown author under the pseudonym “Rex Feral,” the book purported to be a guide to entering the business of contract killings, covering one’s tracks, and resisting the “ego” that comes with being a gun for hire. Over the next ten years, Paladin sold roughly 13,000 copies. At least one of them was delivered to James Perry.

Perry was known in Detroit as a hustler and ambitious street-level entrepreneur. He had done time in the 1970s for armed robbery. While in prison, he met up with a man named Thomas Turner. It was Turner who referred his cousin, Lawrence Horn, to Perry.

Horn was also from Detroit and had spent several years working as a sound engineer for Berry Gordy Jr.’s Motown recording studios. While in the booth, he had supervised tracks for the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, and other highly influential artists. But by the 1990s, the work had dried up.

His personal life also faltered. Horn had been married to Mildred, a flight attendant he met in 1972. In 1985 they had a son, Trevor, who suffered medical problems due to his underdeveloped lungs. Shortly after his birth, the Horns had drifted apart. Their last joint effort was winning a malpractice settlement worth $2 million—including upfront payments to Horn and Mildred of $120,000 and $250,000, respectively.

By 1992, Horn’s share was spent. He was in Hollywood, broke, with his ex-wife demanding past due child support. Horn, prosecutors later alleged, knew the nearly $2 million trust fund was being held for Trevor’s care. He also knew that if anything happened to both Mildred and his son, he would be in line to receive the full amount.

Through Turner, Horn connected with Perry. The two spoke to each other dozens of times over the course of a year, with Horn wiring between $3500 and $5000 to the budding hit man. In March 1993, with Horn in his California apartment, Perry drove to Silver Spring and murdered all three occupants. Within a few weeks, Horn was filing paperwork to claim the trust fund.

Authorities thought this was suspicious. They were also intrigued by several phone calls made by Perry to Horn where Perry insisted on getting more money. Records showed Horn had also received calls from pay phones near a hotel and a Denny’s the night of the murders. Further inquiry showed traces of a criminal who didn't think too quickly on his feet: While Perry paid cash, he willingly handed over his driver’s license when the hotel clerk asked for identification.

Perry and Horn were tried and convicted separately—Horn in 1995 and Perry in 2001 after an earlier mistrial due to an inadmissible phone recording. Prosecutors related that a search of Perry’s residence had uncovered a Paladin catalog as well as evidence of a check sent to the company for two books: Hit Man and a title on how to make an effective silencer.

Before Horn had made his way through criminal court, the relatives of Mildred and Trevor Horn and Janice Saunders pursued civil action against Paladin. Their reasoning was that the publisher had incriminated itself by providing a manual that Perry hadn’t merely skimmed—he mimicked more than 20 specific instructions for getting away with murder.

The author's advice included soliciting business via a mutual friend and using an AR-7 rifle after drilling out the serial numbers. Victims, the book cautioned, should be attacked no closer than a distance of three feet to avoid stains on clothing and to be shot through their eyes to ensure success. After the act, the killer should disassemble the weapon and scatter the pieces in hopes that the authorities would consider the whole operation a bungled burglary. Perry followed each piece of advice to the letter.

In July 1996, U.S. District Judge Alex Williams heard arguments from the families’ lawyer, Howard Siegel, who attacked Paladin. “These manuals were published with the express intention to encourage and facilitate the commission of murder,” Siegel told the Baltimore Sun.

Though Hit Man was labeled “loathsome” by the judge, he declared that the publisher and the book were insulated from charges of aiding and abetting due to the First Amendment.

The resulting publicity was good for sales. Lund told The New York Times orders for the book and others in his catalog were growing. “I know of hundreds and hundreds of books and films that are just as explicit in their instructions,” he said. “I see this dead on as a free-speech issue." (Lund refused to reveal the author's name, though court records obtained by media eventually disclosed the writer was a mother of two who had no apparent history as an assassin.)

In November 1997, a Federal appeals court remanded Williams' decision. In their written declaration, the court found that Hit Man was offered no such protection because any speech aiding and abetting murder was exempt from First Amendment discussion:

Paladin has stipulated that it provided its assistance to Perry with both the knowledge and the intent that the book would immediately be used by criminals and would-be criminals in the solicitation, planning, and commission of murder and murder for hire, and even absent the stipulations, a jury could reasonably find such specific intent… Were the First Amendment to offer protection even in these circumstances, one could publish, by traditional means or even on the internet, the necessary plans and instructions for assassinating the President, for poisoning a city's water supply, for blowing up a skyscraper or public building, or for similar acts of terror and mass destruction, with the specific, indeed even the admitted, purpose of assisting such crimes--all with impunity.

The ruling took free speech advocates by surprise. Several entities, including Disney, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, had signed a letter of support—not precisely backing Paladin, but cautioning that the First Amendment might undergo “serious and substantial” harm.

Lawyers for Paladin appealed to the Supreme Court, but the court refused to hear any further discussion. With the decision set in stone, the publisher was facing the possibility of a jury trial in 1999. Fearing a decision in the plaintiff’s favor would be costly, Paladin’s insurance company elected to settle for an undisclosed sum in the seven-figure range, along with a promise the book would go out of print. The entire case is believed to be the first time in history a publisher has ever been held liable in America—at least financially—for murder.

Paladin still operates out of Boulder, Colorado, selling a variety of titles on lock-picking, spying, and sniping. Lawrence Horn is, at last account, still alive and serving a life sentence. James Perry died in prison in 2009 at the age of 61.

Additional Sources:

“Rice v. Paladin Enterprises”; “FBI Files on Paladin Press, 1972-1998” [PDF].