Orville and Wilbur Wright are generally credited with being the first in flight. Whether that's true depends on your definition of "flight." If you mean controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, then that's what they are known for, but even that may not be quite true, since controlled and sustained are not black-or-white terms. There were plenty of aviation pioneers working on flying in the nineteenth century; after all, we had automobiles and balloons and gliders already, many figured it shouldn't be too difficult to combine them. And there were some substantial cash rewards up for grabs around the turn of the century.

Félix du Temple de la Croix was a French Naval officer who received a patent for a flying machine in 1857. This version never flew, but the steam engine design was successfully used to power boats in later years. By 1874, he had developed a lightweight steam-powered monoplane which flew short distances under its own power after takeoff from a ski-jump.

Alexander Fyodorovich Mozhayskiy was a Russian Naval officer who tackled the problem of heavier-than-air flight twenty years before the Wright Brothers. His 60-100 foot hop of 1884 is now considered a power-assisted takeoff, utilizing a ramp for lift. Since his flatwing monoplane was 75 feet long itself, the event must've been underwhelming. Although not considered a real powered flight, Mozhayskiy made some significant breakthroughs in propulsion and steering. The details of Mozhayskiy's research have been somewhat obscured due to the Soviet's use of his story for propaganda purposes.

French inventor Clément Ader distinguished himself as the first to develop stereo sound, among his many engineering innovations. He was the first to achieve self-propelled flight, with a batwing aircraft powered by a steam engine. His first flight was around 50 meters, on October 9, 1890, a full 13 years before the Wright Brothers! He then designed a better flying machine that reportedly flew 200 yards in 1892. A public demonstration in 1897 apparently ended badly, and Ader lost his Department of War funding. More pictures here.

American-turned-English citizen Sir Hiram Maxim invented the automatic machine gun and the mousetrap. He also fought Thomas Edison over the patent for the light bulb. His airplane, the Maxim Flyer, was enormous. It had a 104-foot wingspan, including a 40-foot center "kite" section. A steam engine powered two 18-foot propellers. The plane was tethered to a railroad track, so the altitude of flight would not exceed nine inches during tests. However, on July 31, 1894, the plane broke free of the restraint and achieved an altitude of almost five feet!

American Augustus Moore Herring applied for a patent for a man-supporting, heavier-than-air, motorized, controllable flying machine in 1896. On October 11, 1899, he flew 50 feet in a glider with a compressed air engine in St. Joseph, Michigan, and flew 73 feet on October 22nd, a flight that was witnessed and reported in the local newspaper. Modern aviation engineers consider Herring's flights as glider flights (resembling a hang glider), and not a significant advance in aviation.

Gustave Whitehead, a German immigrant to the United States, built several airplanes before the Wrights took their first flight. A 1935 account in Popular Avation magazine said Whitehead had flown a steam-powered plane as early as 1899! He was also reported to have flown a gasoline-powered plane on August 14, 1901 in Fairfield, Connecticut. A 1901 newspaper account told the story, but it is the only source from that time period. A reproduction of the airplane Whitehead used in the 1901 flight (known as Number 21) was built and successfully flight tested in 1997, pointing to the possibility that he could have flown earlier than the Wright Brothers.

Karl Jatho of Hanover, Germany tested his flat-winged airplane several times between August and November 1903. His longest flight was less than 200 feet at an altitude of about 10 feet, but it was still motorized flight, months before the Wright Brothers. He later improved the plane design and successfully flew longer and higher in 1909.

The Rev. Burrell Cannon was inspired by the book of Ezekiel when he built the Ezekiel Airship around 1900, with $20,000 from investors. The first model was destroyed during shipping. There is no concrete evidence that the second model ever flew, but four witnesses said they saw it fly at an altitude of about 12 feet in 1902. The Rev. Cannon was not one of the witnesses, as he was preaching that day when his employee, Gus Stamps, reportedly decided to take a spin in the airship. There were no photographs, and no repeat performances. A replica of the Ezekiel Airship is on display at the Depot Museum in Pittsburg. Texas.

Possibly the best claim to successful powered and controlled flight before the Wright Brothers comes from New Zealand. Richard Pearse of Waitohi worked on the problem of powered flight beginning in 1899, and developed an aircraft that quite resembled a modern ultralight. Pearse would have beaten the Wrights by eight months if he hadn't crashed at the end of his 140 meter flight on March 31st, 1903. Or maybe it was the lack of photographs, logs, or written records of the flight. The few eyewitnesses couldn't agree on the length of the flight, or even the exact date. Some accounts place the flight as early as 1902; some as late as 1904. Since the landing wasn't really any rougher than the Wright's landing during that first flight at Kill Devil Hills, the lack of documentation probably kept Pearse out of most history books.

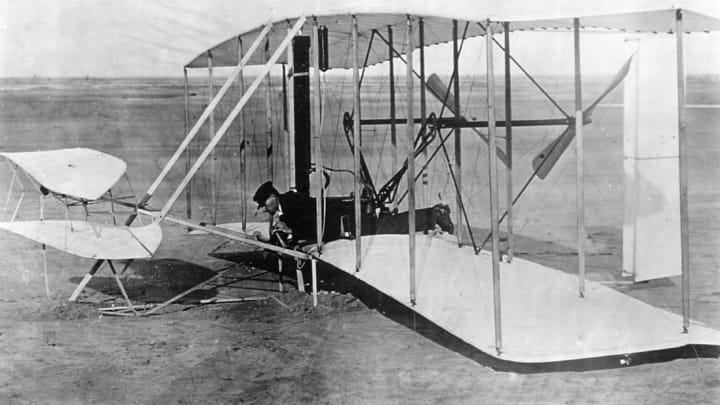

Orville and Wilbur Wright will always be known as the first fliers for several reasons. The design of their successful plane was a breakthrough for the curvature of the wings, which provided lift. They had carefully documented records, photographs, and credible witnesses. They were masters of publicity and promotion; for example, taking President Theodore Roosevelt for an airplane ride (on film) didn't hurt their reputation a bit. And there was that feud with the Smithsonian Institution. The Wright Brothers plane was finally consigned to the Institution in 1948 when the conservators agreed to this stipulation from Orville's estate:

Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.

The science of aviation also owes a lot to the research of those who built planes but never successfully flew. The history of aviation is full of colorful characters, many of whom developed pieces of what eventually became our modern airplanes. Such breakthroughs, of course, continued after the Wright Brother's flight of 1903 and still continue today, but those earliest flights were the most exciting.

Special thanks to Bill for research on this article.