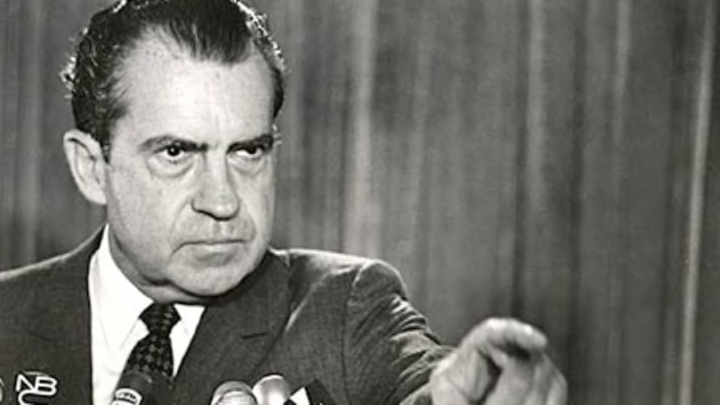

Who knew Tricky Dick was such a wallflower? Believe it or not (and we realize trust might be an issue here), Richard Nixon was a shy child—the kind who played the piano and only followed sports so that people would like him more. Sadly, the awkwardness didn't go away with age. Never a ladies' man, Nixon proposed to his wife, Pat, on their first date, and then obsessively pursued her for two years until she said yes. To spend time with her in the interim, Nixon even drove Pat on dates with other men.

Perhaps all Nixon wanted was a little attention—and in 1948, he finally got it. As a young Congressman, he spearheaded the investigation that exposed former State Department official Alger Hiss as a Soviet spy. The act quickly made Nixon the sweetheart of anti-Communist America. Later, he tried a similar tactic when he ran for Senate in 1950. During the race, he accused his opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, of being a Commie, calling her "pink right down to her underwear." His supporters mailed out thousands of postcards reading, "Vote for our Helen for Senator. We are with you 100%." It was signed "The Communist League of Negro Women Voters." It was neither the first time nor the last time Nixon (or his cronies) would use dirty tricks to advance his career.

Even after making it all the way to the White House, Nixon remained the socially awkward wallflower he'd been in his youth. As president, he did whatever he could to avoid talking to people, especially strangers. He spent hours alone in his office with a yellow legal pad, jotting down lists of enemies and thinking up ways to comport himself better in public. He usually ate lunch by himself at his desk, almost always nibbling on the same meal of rye crackers, skim milk, a canned Dole pineapple ring, and a scoop of cottage cheese.

As part of his insular world, Nixon's phone had direct connections to only three people—Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, and Domestic Policy Advisor John Ehrlichman. (Lyndon Johnson's phone, by contrast, had been wired to 60 people.) The three men formed a protective shield around Nixon, carefully guarding him from face-time with others, including other members of the Cabinet. Collectively, the trio became known as The Berlin Wall.

Is it any surprise, then, that this shrinking violet began to seethe with paranoia? Nixon wanted every room bugged and every conversation recorded. Of course, he never anticipated those recordings being used against him. Practically every moment of Nixon's presidency was caught on tape—tapes that are filled with off-color remarks about Jews, African Americans, and Italians. Of reporters, he once said, "I wouldn't give them the sweat off my balls."

Throughout his career, Nixon employed spies (called "plumbers" because they fixed leaks) to dig up dirt on his political rivals. And if they couldn't find anything through wiretapping or burglary, they often planted evidence. But in June 1972, five of Nixon's plumbers were arrested after breaking into Democratic Party offices in the Watergate Hotel. Nixon used everything in his power to cover up the connection to the White House, but of course, it was all recorded. When the Supreme Court finally subpoenaed the tapes, Nixon was busted. Feeling pretty stupid, he resigned—and the nation hasn't trusted politicians the same way since.

Watergate will always define Richard Nixon's administration. But to be fair, he also accomplished a great deal that benefited the country. Here's a glimpse of the sunnier side of Nixon's presidency.

Special Ops

Nixon wasn't the only president to tape all of his conversations, but he was the only president to do so using a recording device that never stopped. Notoriously bad with electronics, Tricky Dick had trouble remembering how to turn on the tape recorder, so his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, installed a voice-activated system in the Oval Office. It made the president's day-to-day life easier, but it also had one problem: It could never be turned off. Oops!

A Sweet-and-Sour Diplomat

In 1972, a trip to Communist China was a big deal, as America had no formal diplomatic relations with the country. So when Nixon decided to visit Chairman Mao Zedong that February, it shocked the world. But the trip almost ended before it began, when a member of Nixon's advance team—drinking vodka and smoking pot—nearly burned down the hotel where the president was supposed to stay. Nixon was determined, though. It was an election year, and of the 391 people who made up his Chinese entourage, 90 were from the media. Night after night, Americans watched on prime-time television as Nixon and Mao got along famously, and the Cold War began to thaw.

A Patron of the Arts

Champion of Mother Earth

OK, so Nixon didn't really care about the environment. But after the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, public outcry over the destruction of the environment became too great to ignore. How great? The first Earth Day took place on April 22, 1970, and millions of Americans participated. In New York, no cars ran down Fifth Avenue. And in Washington, folksingers Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs sang at the Washington Monument. It was the largest single protest in American history, and Nixon paid attention. During his years in office, he signed the Endangered Species Act, strengthened the Clean Air Act, and created the Environmental Protection Agency.

The Mary Poppins of Smack

Sometimes a spoonful of methadone helps the crime rate go down. In 1968, Nixon campaigned to fight crime by any means necessary. So the following year, after a study found that 44 percent of people entering Washington, D.C., jails were using heroin, Nixon agreed to fund methadone clinics across the city. Within one year, the burglary rate dropped by 41 percent. This should have been a major win for the president, but critics argued that the clinics only substituted one drug for another. The policy never caught on, and to this day, Nixon is still the only president in the war on drugs to have spent more money on treatment than enforcement.