When the Civil War began, the Confederacy quickly found itself facing a pressing issue: fighting a protracted war is really, really expensive. Unlike their Union counterparts, the Confederate states didn’t boast vast reserves of money and precious metals, either. With a Union naval blockade diminishing the lucrative international cotton trade, the Confederacy needed a way to raise some quick cash.

The Confederacy could have gone on a taxation rampage to drum up some funds, but the Southern states weren’t exactly keen on having a national government, even a Confederate one, collecting big taxes. Plus, there wasn’t any infrastructure in place to support mass taxation. Instead, the Confederacy started printing its own money.

As short term solutions go, printing your own cash is a fairly elegant one. You don’t have to levy any unpopular taxes, and as long as people will accept and use the money as a medium for trade, you’re in good shape.

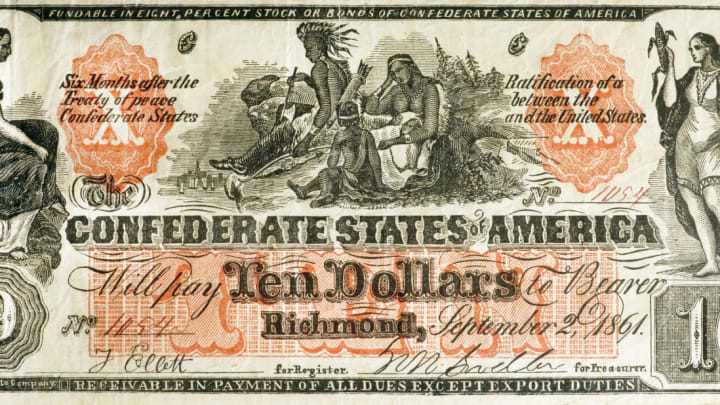

Of course, in the long term, simply setting up a printing press and cranking out money without a comprehensive monetary policy and financial system in place can be a truly terrible idea. The Confederate notes didn’t have any gold, silver, or anything else backing them; instead, they promised to be redeemable for their face value after a certain period of time, say six months or two years, “after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the Confederate States and the United States of America.”

While currencies don’t necessarily have to be backed by anything tangible to be successful – just ask the euro or the dollar - astute readers have already noticed the rub in this system: the bills would only be redeemable if there were still a Confederacy around to cash them after the ratification of a peace treaty. If the Union came out on top, the Confederate money would be worthless. In addition to this gamble about the war’s outcome, the Confederacy kickstarted inflation in its states by continuing to print more and more of the currency. In a lesson straight out of freshman economics, as the supply of Confederate bills shot up, their value crashed.

By the time the Confederacy dissolved on May 5, 1865, the currency was already effectively worthless. The combination of the inflation that had kicked in as the Confederacy kept printing more money and Southerners’ growing skepticism about the continued existence of their breakaway government cratered the currency. At the war’s end, the value of 100 Confederate dollars had plummeted to $1.76, which equates to a rate of inflation of around 9,000 percent.

When the South failed to rise again (at least in Confederate form), many Southerners were left sitting on giant piles of worthless currency from a defunct country. Tough luck, to be sure, but what they may not have known was that they could just have taken a voyage to Germany to recover some of their lost value. On May 30, 1909, The New York Times ran a story under the headline “CONFEDERATE MONEY TAKEN: German Shopkeepers Apparently Ignorant That Civil War Is Over.”

According to the story, many merchants, hoteliers, and café proprietors in Berlin were still accepting Confederate cash that hadn’t been worth its face value in over four decades. The American consulate in Berlin had been fending off German businessmen who were trying to exchange their notes from, say, the Bank of Richmond for German currency. Whoops. The article closed with the line “[S]ome of [the merchants] have left the consulate convinced that the United States Treasury has really ceased payment and is ashamed to admit it.”

The Germans eventually wised up, but apparently this question still comes up from time to time. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing feels compelled to explicitly state on its website that “Confederate States Notes were not produced by the BEP and are not obligations of the United States Government.”

Just because you can’t take your Confederate money to the bank or use it to pay off a parking ticket doesn’t mean it’s worthless, though. There’s a collector’s market for the bills that can be quite lucrative. While most bills probably aren’t valuable enough to pay Stonewall Jackson’s salary, a quick scan of eBay auctions shows that even the rattiest examples of small-denomination bills regularly sell for over $10. Mint, uncirculated bills in higher denominations can fetch hundreds of dollars at auction.