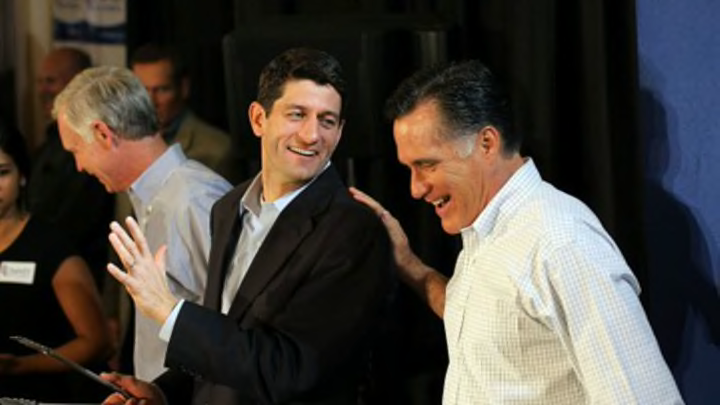

This morning Mitt Romney tapped Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan as his running mate. John Nance Garner, FDR's first vice president, either said the VP position wasn't worth "a warm pitcher of piss" or "a warm bucket of spit." Whatever body fluid and receptacle he really used, you get the idea. But that doesn't mean there haven't been some wild scandals along the way.

1. Chester Arthur Was Canadian!

Even with the kickback scandal and claims that he'd been born in Canada (which should've disqualified him for the vice presidency), Arthur still managed to get elected on James Garfield's 1880 ticket. After Garfield passed away 199 days into his presidency, Arthur didn't hesitate to sign the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. Much to the chagrin of Conkling, the Act revamped civil service by effectively killing the same patronage system that made Arthur very, very rich. In cleaning up civil service, Arthur also cleaned up his reputation, and he exited the White House a hero.

2. William Rufus de Vane King was (Pretty Definitely) Gay

Pierce's VP

William R. King was sworn into office in Cuba, becoming the only executive officer to take the oath on foreign soil. King had gone to Cuba to recuperate from tuberculosis and severe alcoholism, but it didn't work. He died in 1853 after being vice president for just 25 days.

That might not be the most memorable thing about King, though. It's widely rumored that the former VP was homosexual. Further still, he's suspected of being James Buchanan's lover. Neither King nor Buchanan ever married, and they lived together in Washington for 15 years before Buchanan became president. Of course, King's predilection for wearing scarves and wigs only fanned the rumors. President Andrew Jackson used to call him "Miss Nancy," and Aaron Brown, a fellow Southern Democrat, dubbed him "Aunt Fancy."

3. Henry Wallace: Soviet Apologist

As vice president, Wallace made many international goodwill trips. Most famously, he traveled to the Soviet Union, where he experienced a political transformation that resulted in him becoming an avowed Soviet apologist. His communist leanings did nothing for his image, especially once he became secretary of commerce under President Truman. In 1948, Wallace unsuccessfully ran for president on the Progressive Party ticket, espousing views that sounded shockingly Marxist. He even described corporations as "midget Hitlers" attempting to crush the labor class.

But nobody can say Wallace didn't know how to own up to his mistakes. In 1952, he recanted his support of the Soviet Union in a magazine article called "Where I was Wrong." By then, however, his political career was over. Wallace spent the rest of his life conducting agricultural experiments on his farm in New York. [Image courtesy of Ron Wade Buttons.]

4. Richard M. Johnson's 3 Black Mistresses

Van Buren's VP

Despite his credentials as a war hero and a Kentucky senator, Vice President Richard M. Johnson was never accepted in Washington. Perhaps that's because he dressed like a farmhand, cursed like a sailor, and made no secret of his three black mistresses, who were also his slaves. The first mistress bore him two daughters before she passed away; the second tried to run off with a Native American chief, but Johnson captured and resold her; and the third was the second one's sister.

Johnson attempted to introduce this third mistress into polite society, but the couple wasn't well-received. With the support of Andrew Jackson, Johnson landed the vice presidency under Martin Van Buren in 1836. After four years of public relations disasters, Jackson withdrew his support. Nonetheless, Van Buren kept Johnson on his ticket, and the two lost their re-election bid in 1840.

5. Aaron Burr Was a Cassanova

The plan could have worked, but one of Burr's co-conspirators ratted him out. He was tried in 1807 before the Supreme Court, which found him not guilty, mainly because he hadn't actually committed the treason yet. A free man, Burr turned his sights on Florida. He went to France and tried to convince Napoleon Bonaparte to help him conquer the swampland, but that plan foundered, too.

Although his political high jinks often failed, Burr consistently found success with the ladies. After his wife died in 1794, Burr remained a bachelor for 40 years, making the acquaintance of several eligible socialites. He enjoyed flirtations with Philadelphia debutantes, as well as a widow named Dolley Payne Todd—later known as Dolley Madison, wife of James Madison. At age 76, Burr married a wealthy widow of ill-repute and plundered her fortune. Citing numerous infidelities on his part, she filed for divorce and was actually granted it. Unfortunately for her, it came through on the day Burr died.

6. John Tyler Borrowed Cash to Get to His Inauguration

William Henry Harrison's VP

When President Harrison succumbed to pneumonia in 1841 after only a month in office, John Tyler became the first vice president to take the Oval Office as the result of a president's death. Understandably, he was totally unprepared for the job. Like previous VPs, Tyler had expected to carry the title without responsibilities. He'd actually taken such a lax approach to the position that he was enjoying life on his Virginia farm when a messenger brought news of Harrison's demise. Tyler had to borrow money from a neighbor to catch the riverboat back to Washington.

As president, Tyler's administration was largely unremarkable, except that he annexed the Republic of Texas and became the first president to have Congress override his veto. Tyler was also the first president to receive no official state recognition of his death. Why? By the time of his passing in 1862, he was an official in the Confederacy.

7. Andrew Johnson Took the Oath Sloshed

Needless to say, his address was poorly received. The New York World opined, "To think that one frail life stands between this insolent, clownish creature and the presidency! May God bless and spare Abraham Lincoln!" Unfortunately, God didn't. The South surrendered six days before Lincoln's assassination, leaving Johnson to handle Reconstruction—a job he bungled so completely that Congress moved to impeach him. Johnson avoided being booted out of office by just one vote.

8. John Breckinridge Hid Out in Cuba

Buchanan's VP

By all accounts, John C. Breckinridge was a Kentucky gentleman in the grandest sense. He had an impressive career as a lawyer and a representative in the Kentucky House. More notably, at age 36, he became the youngest vice president in history. But, like Aaron Burr, things took a turn for Breckinridge when he was charged with treason. In September 1861, only a few months after his vice presidential term had ended, Union and Confederate forces invaded his home state of Kentucky. Breckinridge cast his lot with the Confederates, and the federal government promptly indicted him.

Breckinridge headed south and became Jefferson Davis' secretary of war. But when the Confederacy surrendered in 1865, Breckinridge was forced to go on the lam. He hid for the next two months in Georgia and Florida before escaping to Cuba. Breckinridge, his wife, and their children spent the next four years in exile, wandering through Canada, England, Europe, and the Middle East, until President Andrew Johnson issued a General Amnesty Proclamation on Christmas in 1868. The following March, Breckinridge returned to the country with his family, but his name wasn't officially cleared until 1958, when a Kentucky circuit court judge dismissed his indictment.

9. Nelson Rockefeller Tore Down That Wall

Rockefeller quickly gained a reputation as a rather strong-willed person. In 1933, he commissioned Mexican artist Diego Rivera to paint a large-scale mural in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. The mural featured a likeness of Vladimir Lenin, and the overt reference to communism offended Rockefeller. He asked Rivera to change it to a face of an unknown man, and the artist refused. In response, Rockefeller had the whole mural torn down and carted out in pieces.

Rockefeller was equally dissatisfied with his gig as vice president. He refused to run with Ford on the Republican ticket in 1976.

10. Spiro Agnew, the Archie Bunker of the White House

Nixon's VP

Spiro Agnew, who preferred to be called Ted, was a seemingly safe choice for Richard Nixon's running mate in 1968—mainly because he faded easily into the background. But once in office, Agnew thrust himself into the limelight. By delivering a series of divisive speeches defending the Vietnam War and attacking peaceniks, Agnew became the crotchety Archie Bunker of the White House. He lambasted his enemies, peppering his rants with phrases such as "supercilious sophisticates," "vicars of vacillation," and "pusillanimous pussyfooting."

Still, much of the country loved him, especially as he remained unsullied by the Watergate scandal. When word got out that the Justice Department was investigating him for extortion and bribery, Agnew vehemently denied the charges. In September of 1973, Agnew spoke at the National Federation of Republican Women in front of thousands of screaming fans, many bearing "Spiro is our Hero" signs. He swore to them, "I will not resign if indicted!"

Two weeks later, however, he did just that. Agnew agreed to a plea bargain that involved leaving his post as vice president and paying $150,000 in back taxes. A former lawyer, Agnew was disbarred and took up writing to pay off his debts. In 1976, he penned The Canfield Decision, a tale of a vice president who becomes involved with militant Zionists and is consumed by his own ambition. In 1980, he covered some of the same ground in his autobiography, Go Quietly ... Or Else.

This article originally appeared in mental_floss magazine.