Dan Lewis runs the popular daily newsletter Now I Know ("Learn Something New Every Day, By Email"). We've invited him to share some of his stories on mental_floss this week. To subscribe to his daily email, click here.

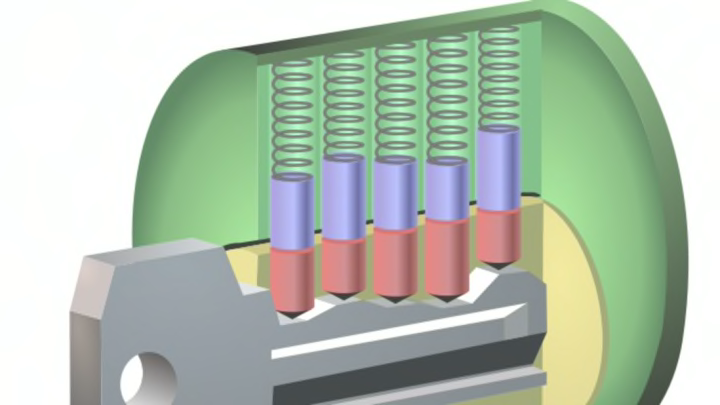

If your house has a standard door knob lock (a “pin tumbler lock”), the way it works is described graphically above (image via Wikipedia). The red and blue parts, combined, are called a “pin stack.” The blue pins, called “driver pins,” are spring-loaded, pushing the entire pin stack down. When there is not a key inserted into the lock, this prevents the lock from turning. But when a key is inserted, it pushes the red pins, called key pins, upward. If the key is the right one, the tops of the key pins (and therefore the bottom of the driver pins) form a straight line, called a shear line. With the pins now separated along this line, the key can turn, unlocking the door. It’s a neat, clean way to keep things safe.

Unless a thief or other miscreant knows about “lock bumping.”

Most pin tumbler locks are vulnerable to this crude, inexpensive-to-exploit flaw, which requires nothing more than a hammer and something called a “bump key.” The bump key is a special type of key with shallow, uniform teeth, allowing it to be inserted into the lock without risk of being thwarted by the presence of a deep pin stack. The bump key is inserted almost entirely into the lock, with one slot left exposed outside the mechanism. (The key will be pushed fully into place by the hammer rap to follow.) Once the bump key is properly inserted, the key pins rest on it while the driver pins, in turn, rest on the key pins with springs extended.

The villian then, ever so slightly, tries (at this point, in vain) to turn the key, but again, only slightly. The goal here is not to push the driver pins against their chambers, locking them in place, but to get the key going in the right direction when the magic happens in the next, and final, step. Our bogeyman takes the hammer and bangs it firmly against the key. The force exerted by the hammer is transferred to the key pins, and, like the desk top toy Newton’s Cradle, causes the key pins and driver pins to separate for a fraction of a second. And because the key is already being slightly turned, this momentary separation is more than enough time for the locking mechanism to be disabled. The key turns and the lock is unlocked.

Is your lock vulnerable? Most likely, yes, although many newer pin tumbler locks come with countermeasures, such as foam inserts which absorb the force from bumps.

To subscribe to Dan's daily email Now I Know, click here. You can also follow him on Twitter.