There are three fathers of invention when it comes to nearly every car on the road today: Otto, Diesel, and Atkinson. They all had one thing in common—a drive to improve the efficiency of the engines available in the late 1800s. Each man succeeded, though Atkinson’s success with his engine innovation wouldn’t be put into use for many, many, many years (more than a century, in fact).

1. Nikolaus Otto

Wikimedia Commons

Nearly everyone has heard of a diesel engine, but nearly everyone actually has an Otto-cycle engine. Call it a four-banger, a five-point-oh, a V8, or any other gearhead term—they’re all internal combustion Otto engines.

Otto was a high-school dropout who worked in a grocery store, as an office drone, and as a traveling salesman in Germany in the mid-1800s. Lucky for us, he also had a mechanical bent. At the time, engines used external combustion—the fuel source fired up outside the engine itself. That meant the engines were stationary; they could only power machinery in factories, not fit under a hood and go tootling around the German countryside.

Having been a traveling salesman, Otto wanted a way to travel his route more quickly. So he came up with a way to introduce the gasoline into the cylinder itself, and thus was born the first two-stroke internal combustion engine in 1864. He used this first stroke of genius to found Otto & Cie, now the world’s oldest manufacturer of internal combustion engines (it’s changed names a few times over the years; it’s now Klockner-Humboldt-Deutz). He used his second stroke of genius to hire a couple of young engineering upstarts whose names might sound familiar: Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach.

The ensuing four-stroke engine was patented in 1877, though the patent was later disputed and revoked. In any case, the “Silent Otto” engine, as it was known, made 3 hp at 180 rpm. Hold onto your bonnet, Mildred! That is not powerful.

2. Rudolf Diesel

Wikimedia Commons

Diesel was born in France in 1858, but he spent much of his young life in Germany, where the engineering field was hotter than bratwurst. He himself became a thermal engineer, and he held several patents related to refrigeration. But it was the other end of the thermal scale that would make Diesel famous.

He saw what Otto was doing and thought he could make the process of burning fuel to create usable power more efficient. His solution was to put air under such high pressure that it got hot. Really hot. Spontaneous-combustion hot. Then, when fuel of any kind was introduced—even peanut oil—it would ignite without needing a spark.

This went over like gangbusters when he filed the patent in 1894. By 1898, Diesel was a millionaire. But in 1913, Diesel’s body was found floating in the North Sea. He had been on his way to England from Belgium to open a new engine factory and talk to the British Navy about using his engine in their submarines. Conspiracy theories flew: Was he murdered by Big Oil for his engine’s efficiency? Or by Big Coal, whose products powered ships and factories? Or by Germans afraid he was selling out to the Brits? Or did he leap from the deck in a fit of depression, as he was nearly broke at the time?

Your guess is as good as anyone else’s. But in the meantime, we can thank his pioneering use of peanut oil for our ability to dump biodiesel, French fry grease, and any manner of alternative fuels into modern diesel engines without harm.

3. James Atkinson

Let’s clear up a point of inventor-related confusion right now: this is not the same guy who built the mousetrap with the snapping wire. That’s another English inventor named James Atkinson. This is the guy who looked at what Otto and Diesel were doing and thought, “I can make that more efficient.”

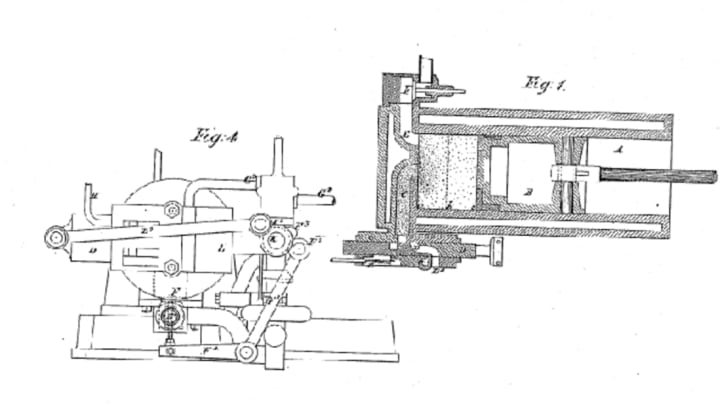

Atkinson’s stroke of genius was singular and irregular. Singular because in the engine he created in 1882, all four strokes (intake, compression, ignition, exhaust) were completed in one turn of the crankshaft. Irregular because he figured out how use uneven strokes to shorten the intake stroke—which means less fuel is used—and lengthen the power stroke to maximize the effect of that fuel. It was a very efficient engine, and also very unwieldy, with its complicated linkages. It didn’t catch on at all in the early days of automotive history. Steam engines made more sense to people than this contraption.

But then, at the turn of the next century, gasoline-electric hybrids hit the scene. They had lots of power up front, thanks to their electric motors, but it petered out pretty quickly. Atkinson engines were exactly the opposite: The shorter intake stroke meant less fuel was being used, but it also meant that no matter how long that power stroke was after ignition, it wasn’t going to be as powerful as the one in an Otto engine.

It turned out that Atkinson-cycle engines and electric motors went together like chocolate and peanut butter in a Reese’s cup. They combined to showcase their best sides and accommodate each other’s flaws. Of course, now the uneven strokes are achieved using variable valve timing and other electronic tricks, but the idea is the same as Atkinson’s original, even after a century of languishing, unloved, on the patent office shelves.