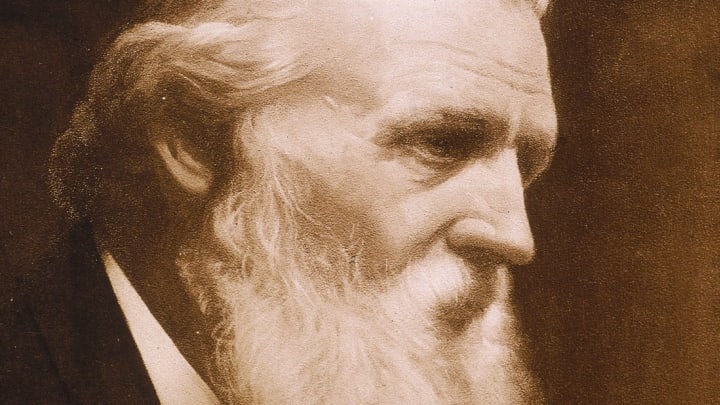

When you think of John Muir, you might envision a bearded naturalist on a hike or standing in front of a magnificent natural vista. But Muir was more than a great explorer and advocate of national parks—he was also an ingenious inventor.

As a young boy in Scotland and later Wisconsin, Muir developed an obsession with clocks. There was just one problem: His authoritarian father, Daniel, filled every waking hour with chores and religious education. By the time he was 11 years old, John could recite three-quarters of the Old Testament and the entire New Testament “by sore flesh,” as he wrote in his memoir, a reference to the brutal beatings his father inflicted on him if he failed to fulfill his duties.

Daniel Muir had little patience for his son’s budding interest in engineering. So John came up with a solution: wake up earlier than the rest of the family and try out ideas he had come up with while plowing during the day. He began to get up at 1 a.m. to read.

“Five hours, almost half a day!” he later wrote. “I can hardly think of any other event in my life, any discovery I ever made that gave birth to joy so transportingly glorious as the possession of these five frosty hours.” Soon he was doing more than reading: In the wee hours of the morning, he made a labor-saving sawmill.

His creativity stoked by his first success, Muir decided to figure out a way to make the most of his precious morning hours. The “early-rising machine,” as he called it, was not just a way to work on his engineering skills, it was a way to make sure he got out of bed. In his memoir of his boyhood, Muir describes the invention as “a timekeeper which would tell the day of the week and the day of the month, as well as strike like a common clock and point out the hours; also … have an attachment whereby it could be connected with a bedstead to set me on my feet at any hour in the morning; also to start fires, light lamps, etc.”

Muir faced several obstacles in creating his ambitious invention, however: Not only were his days crammed full of work, but he lacked both the raw materials and his father’s permission to spend time whittling instead of working. For months, Muir hoarded small scraps of wood, carving them in every spare moment, and hid his invention in a spare bedroom upstairs.

When his father finally discovered the machine, Muir thought he would burn it. But after delivering a lecture about the wickedness of spending spare time on “useless, nonsensical things,” he did nothing—and Muir finished it in full view. Despite his naysaying, Muir’s father even seems to have tried it out. “This he did repeatedly,” wrote Muir, “and evidently seemed a little proud of my ability to invent and whittle such a thing, though careful to give no encouragement for anything more of the kind in the future.”

Not that Muir needed much encouragement. Once his early-rising machine was finished, he made even more wooden clocks, including one shaped like a scythe that included the uplifting message “all flesh is grass.” Another clock was so large it could be read by the neighbors. (Muir’s father put a stop to that, fearing that it would draw too many onlookers.)

Once Muir got to college, he kept on inventing clocks. His dorm room at the University of Wisconsin, Madison doubled as a workshop, and he invented another alarm clock designed to help him excel in school. This desk alarm clock was perhaps his greatest mechanical triumph: Not only did it wake him up in the morning, it lit a lamp to illuminate the room, and after giving him a few minutes to dress, served up the first in a stack of study books—even opening the book up for Muir to read. A clicking device held the book in place for a specified amount of time, before closing it, sweeping it away, and putting the next book in its place. Muir even modified the machine to respond to the morning sun during the summer, using a glass lens on his windowsill to burn through a thread that would snap and trigger the clock’s mechanism.

But Muir’s most impressive invention didn’t involve wheels, cogs, or mechanics. Though he gained a reputation for his engineering, a machine accident that left him partially blind in 1867 pushed him more and more to his other love, the outdoors. In 1889, Muir drew a map that would change the world—a map of the boundaries of land in Yosemite, which he thought should be preserved by the federal government.

This led not just to the creation of Yosemite National Park, but to the Sierra Club—an organization Muir co-founded on May 28, 1892—which has advocated for the conservation of America’s natural glory for 125 years. Today, the inventor-turned-naturalist is considered one of the grandfathers of American preservation, but it all started with a curiosity honed during stolen hours, helped along by some very clever clocks.