Fortune-telling automata—think Zoltar—were a fixture of penny arcades and amusement parks for generations of schoolchildren. But these creations owe their origin in part to the literary legend of the brazen head, an imaginary all-knowing mechanical device supposedly endowed with the ability to answer any question and predict the future. Called brazen because they were made of brass, their popularity peaked in the Renaissance, when plays and romances featured them and thinkers pondered the supposed mysteries of their making.

"A NATURAL MAN'S HEAD"

The most frequently referenced brazen head is the one allegedly made by 13th century Franciscan friar and philosopher Roger Bacon, although stories of its creation don't appear until centuries after his death. The anonymous 16th century prose romance The famous historie of Fryer Bacon describes the magical object as a precise brass replica of a “natural man’s head,” including “the inward parts,” and tells how Bacon, struggling to give it speech, summoned the Devil to ask him for advice. Satan announced that the head would speak after a few weeks, as long as it was powered by “the continuall fume of the six hottest simples,” a selection of plants used in alchemical medicine.

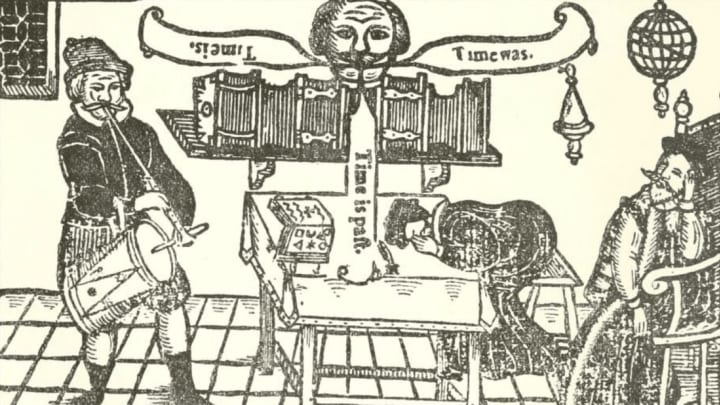

The tale formed part of the plot of the popular play Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, written by English dramatist and pamphleteer Robert Greene and first performed around 1589. In both accounts, Bacon’s ultimate purpose was to build a magical wall of brass around Britain to protect it against any invasions; the all-knowing head would have assisted him in the task. There is, however, a crucial difference: In the play, the “monstrous head” isn’t built by alchemy nor by natural magic, but by “necromantic charms." In both sources, when the magical creation finally speaks, Bacon is fast asleep and misses its words—“Time is,” “Time was,” and “Time is past.” The opportunity to question his creation about the secrets of the universe is gone, and the head explodes, destroying itself.

Never mind that Bacon was an expert in geometry and mathematics and one of the pioneers of the scientific method; rumors that he had built a brazen head “by the hand of the Devil” persisted well into 17th century. The extent of Bacon's magical doings during his lifetime is a subject of much debate, but his association with the demonic may come in part from his experiments in optics, which resulted in impressive tricks of perspective judged to have been done “by power of evyll spirites,” in the words of the 16th century mathematician Robert Recorde. And while there is no record of Bacon ever creating an actual brazen head, he was fascinated by early astronomical clocks—also made of brass, and also offering information about the cosmos.

Bacon was a disciple of bishop Robert Grosseteste, another polymath alleged by literary legend to have made a brazen head, in his case by using “astral science” with the purpose of predicting the future. There are many similarities between the stories—particularly the fact that Grosseteste was also asleep when the brazen head delivered its cryptic words—so it’s likely that the two tales may have influenced one another over the years. And like Bacon, Grosseteste wasn’t exactly a sorcerer: Centuries after his death, he remains an influential figure in mathematical physics, still remembered as a crucial name in the development of Oxford University, where he lectured.

Even a saint was said to have made a brazen head. Renaissance sources tell us that 13th century Saint Albertus Magnus spent 30 years building a man of brass able to correctly answer any question, but according to one version of the story, the automaton was so loquacious that a disciple of Saint Albertus—the famed Thomas Aquinas—knocked it to pieces to stop its constant chattering.

Yet the earliest known written reference to something like a brazen head predates the Renaissance, and appears in the 12th century Chronicle of the Kings of England by William of Malmesbury. The historian attributes the creation of this head to Gerbert of Aurillac, who would become Pope Sylvester II in 999. We’re told that Gerbert traveled to Spain to “learn astrology and other sciences of that description from the Saracens,” and that he stole a book of spells from a Saracen philosopher before making a pact with the devil, who was responsible for his rise to the papal throne. “By a certain inspection of stars,” Gerbert built a head that accurately answered “yes” or “no” to any question—including one about its creator’s death. (Gerbert may have been clever enough to create an omniscient figure, but he failed to ask it the right questions: Told that he would only die after singing mass in Jerusalem, death nevertheless caught him by surprise days after having sung mass not in the city of Jerusalem, but in Jerusalem Church in Rome.)

William’s account is key to how the legend of the brazen head was received and interpreted. As a Christian monk, he regarded Islam as unholy. When Gerbert meddled with Saracens (a term medieval Europeans commonly used for Arabs and later Muslims) he was understood to have opened a door to the occult, introducing a “demonic” object to the Western world. William also perhaps strengthened the connection to paganism in the text by mentioning Daedalus, the cunning craftsman of Greek mythology, who fathered Icarus—and an impressive number of ancient automata.

INGENIOUS DEVICES

There was, indeed, some truth behind these stories. Ancient automata were not a mere mythical creation, but a real product of the inventiveness of some very early engineers. In the 4th century BCE, Archytas of Tarentum created a steam or compressed-air-powered dove; 3rd century BCE Philon of Byzantium designed a wine-pouring maid; and 1st century CE Hero of Alexandria produced a series of mechanical devices that included coin-operated machines, puppets, singing birds, and even a miniature theater able to stage a tragedy. This Greco-Alexandrian tradition was carried forward by Arab-Islamic engineers, such as the Banū Mūsā brothers in 9th century Baghdad, whose Book of Ingenious Devices contains designs for several different automata.

If many Christians regarded these inventions as devilry, it wasn’t just for their seemingly unnatural qualities, but also for their pagan origins.

Back in early modern England, Protestants used the brazen head motif for their own political purposes. In Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, Bacon—who like Gerbert, Grosseteste, and Albertus Magnus was an intellectual working on advanced ideas of philosophy and nature—is presented as a necromancer. The influential play is an example of Reformation propaganda: The Middle Ages are depicted as a breeding ground for magic and the occult, and Catholics are portrayed as credulous and superstitious, as opposed to Protestants, who are praised as advocates of progress.

MAGICAL RELICS

The fascination with fortune-telling heads didn’t end with the Renaissance, however. Centuries later, the legend of Bacon’s brazen head still breathed in the works of Daniel Defoe, Lord Byron, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. In A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), Defoe describes how brazen heads were “the usual sign” that marked the dwellings of fortune-tellers and astrologers in 1665 London. What may have been false advertising in the 17th century became reasonably accurate in the penny arcades of the 20th century, where the fortune-telling business was actually performed by machines.

Many of these more recent fortune-telling creations still trade on tropes of the exotic—elderly gypsy women, Central European magicians, or Eastern mystics. While such automata are increasingly rare, several now live in museums, such as the Musée Mécanique in San Francisco or the Tibidabo Automata Museum in Barcelona. Although not the brazen heads of legend, they’re still functioning, ready to tell us our future—as long as we don't fall asleep.