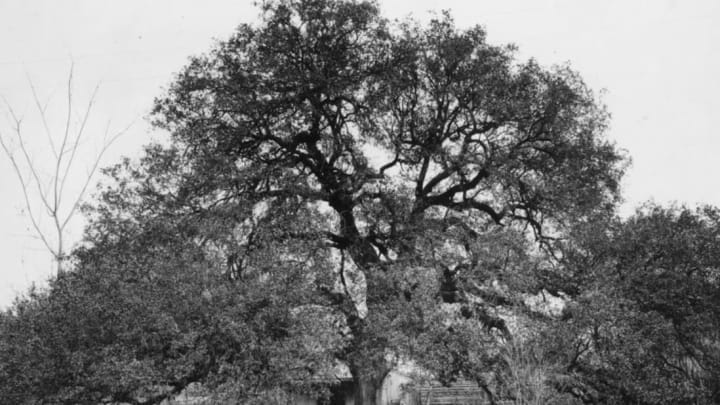

A Southern live oak that presides over Baylor Street in Austin, Texas predates the city itself. For centuries, the Treaty Oak awed onlookers with its mighty trunk and sweeping branches that covered an area nearly 130 feet across. Its elegance was celebrated far beyond Austin: In 1927, the American Forestry Association named it the most perfect specimen of a North American tree.

Then, in 1989, residents noticed something peculiar about the 600-year-old landmark: A patch of dead grass had popped up beneath it, and soon after the tree began showing signs of disease. But it wasn’t the victim of a virus or an unfortunate mistake; someone had saturated the roots with large quantities of plant poison with the intention of taking the tree’s life.

Former Austin forester John Giedraitis was one of the first people to learn of the crime. Hoping to get to the bottom of the oak’s symptoms, he sent soil samples to the Department of Agriculture for analysis. Tests revealed that the dirt contained Velpar, an aggressive liquid herbicide used by pine foresters to kill any non-pine plants that invade their plantations. A few ounces of the compound is enough to kill a full-grown tree; the Treaty Oak had been poisoned with up to a gallon of the stuff. “We knew there was no accident,” Giedraitis told the Criminal podcast years later. “There was absolutely no reason to put this stuff at the bottom of this tree unless you wanted to kill the tree.”

When news of the poisoning spread throughout Austin, residents were outraged. The tree was a treasured part of the region’s history: Before European-Americans settled the land around it, the tree was revered in Tejas, Apache, and Comanche culture. A plaque beneath the site tells the (unsubstantiated) story of Texas settler Stephen F. Austin negotiating a border treaty with Native Americans on that very spot in the 1830s.

In an attempt to save the dying tree’s life, the city launched a full-blown recovery campaign. The contaminated soil was replaced with fresh dirt and the damaged roots were treated with sugar. A sprinkler system was installed in Treaty Oak Park to provide the tree a steady supply of revitalizing spring water. Other efforts were less practical: a Dallas-based psychic named Sharon Capehart tried healing the tree by transferring energy into it. (In the process, she allegedly discovered that its spirit had once belonged to an ancient Egyptian woman named Alexandria.) Without any supposed psychic gifts or tree expertise to offer, some Austin citizens responded with good vibes. Visitors made small gifts and “get well” cards that quickly piled up beneath the tree’s canopy.

As the public processed the shock and grief, the Austin police worked to nab the perpetrator. On June 29, 1989—a few months after the crime had been committed—they arrested their primary suspect: a 45-year-old local named Paul Stedman Cullen. He was convicted on a second-degree criminal mischief charge nearly a year later. His motive? Cullen poisoned the tree as part of a mystic ritual. “Prosecutors said he used the herbicide in an occult ritual to kill his love for his counselor at a methadone clinic, protect her from another man, and pay back the state for outdoor work he was forced to do while he was in prison,” The New York Times reported in 1990.

Before pouring the Velpar on the oak’s roots, Cullen had placed objects that belonged to his counselor in a circle around the trunk. He told an acquaintance that every time he passed the tree and saw it dying he would “see his love for the counselor dying.” The jury had the option to sentence him to life in prison, but in the end they settled on a sentence of nine years (which he served a third of) and a $1000 fine.

Cullen only lived to age 57 after he was released from prison. The Treaty Oak, however, endured: Though it’s only a third of the size it was in its prime, the tree remains a thriving and beloved part of the community. Acorns gathered from the tree’s first post-poisoning germination in 1997 were planted around Texas and the greater U.S., creating opportunities for the Treaty Oak’s legacy to live on for centuries to come.