Ithaca, New York is home to perhaps the world’s spookiest library repository. The Cornell Witchcraft Collection contains more than 3000 books, manuscripts, and artifacts, providing a historic overview of European magic, superstition, and persecution. These items are typically accessible to the public only by appointment—but starting this Halloween, a new exhibition will allow visitors to get up close and personal with an assortment of witchy relics.

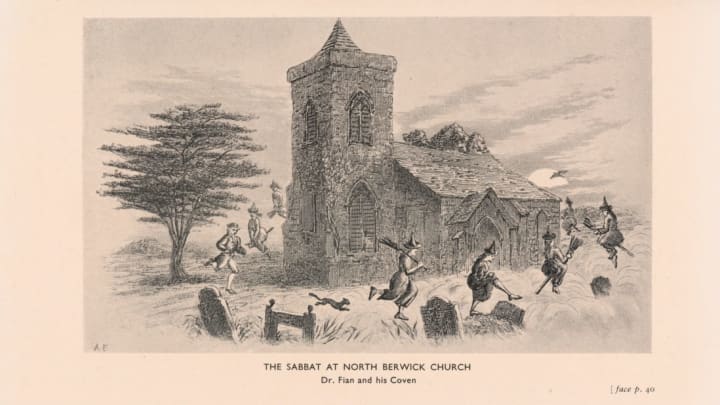

“The World Bewitch’d” will be the university’s first full-fledged exhibition dedicated to the Cornell Witchcraft Collection. Containing around 200 items—including rare books, handwritten trial transcriptions, early images of witches in flight, and more—it will trace how societal views of witchcraft have spread and evolved over the past few centuries, in addition to telling the stories of real-life trial victims. It will also include popular culture depictions of the witch, including 20th and 21st century movie posters.

Cornell’s Witchcraft Collection was originally compiled in the 1880s by university co-founder Andrew Dickson White and his librarian, George Lincoln Burr. White “was interested in things at the margin,” Anne Kenney, a now-retired Cornell University librarian who co-curated “The World Bewitch’d,” tells Mental Floss.

In addition to witchcraft materials, White also collected anti-slavery and Civil War pamphlets, and had a particular fascination “with those who were oppressed and subject to discrimination,” Kenney says. White ended up amassing North America's largest collection of witchcraft artifacts, and one of the world's largest collections of slavery and abolitionist materials.

“The World Bewitch’d” will include a mix of contemporary and archival items, says Kenney, who co-organized the exhibit along with Kornelia Tancheva, another former Cornell librarian. It also contains plenty of “firsts”: the first-known book on witchcraft ever printed, the first printed image of witches in flight, and the first-known illustration of the devil claiming an evil spirit, to name a few.

The first book on witchcraft was printed in 1471, and was authored by Alphonso de Spina, a Spanish Franciscan bishop, preacher, and writer. Called Fortalitium Fidei (Fortress of Faith), it “describes the various threats to the Catholic faith, and the last of those threats dealt with the war of demons, which also included witchcraft,” Kenney says.

Also on display will be the Nuremberg Chronicle, the 1493 Biblical world history text by Hartmann Schedel. It contains a woodblock print of the Devil carrying off the Witch of Berkeley, a figure from English folklore. This image “helped popularize the link between the practice of witchcraft and the devil,” Kenney says. “It was reproduced around the 16th century, and lots of people mimicked it in their representation of witches.”

Meanwhile, the first printed image of witches in flight comes from legal scholar Ulrich Molitor’s 1489 treatise on witchcraft, De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus. It was the first witchcraft book to contain woodcut illustrations, although his witches in flight straddle wooden forks instead of brooms. (Brooms were a “later conceit,” Kenney says.) The witches are presented as animals, to demonstrate their purported shape-shifting abilities.

While largely concerned with popular representations of witches, other parts of the exhibition will shift visitors’ focus back to real-life victims of persecution. One exhibition case will focus on two sensational trials that involved men, including the story of Dietrich Flade, a high-ranking judge in the city of Trier, Germany, whose opposition to witch trials led to his own accusation, torture, and execution in 1589. Another will tell the tales of seven individual women who were accused of witchcraft.

The gendering of witchcraft is yet another key theme in the exhibition—around 80 percent of accused witches were women, Kenney says. Most of the accused women included in “The World Bewitch’d” "had reputations of being difficult and ill-tempered—one of the signs of being a witch was if you swore or cursed,” Kenney says. “Women who were highly independent, and not subservient, might have been more subject to being targeted. All of these women suffered torture. Only two of them—two sisters—were declared innocent, because one of them withstood torture for quite a bit of time and did not confess to any crimes.”

In short, "The World Bewitch'd" "isn't an exhibition to take trick-or-treaters to," Kenney laughs. But it's still a must-see for anyone interested in the history of witchcraft—or those who prefer to get their thrills from libraries instead of haunted houses.

"The World Bewitch'd" will go on display in Cornell's Carl A. Kroch Library in the Hirshland Exhibiton Gallery on October 31 and run through August 31, 2018.