It’s the best-known soliloquy in the world. Hamlet: To be or not to be! The chances are you know it already, and it’s likely that when you’re seated in the stalls of your local theater, after the stage clears and the actor playing the young prince steps into the spotlight, you’re able to mouth along with him:

“To be or not to be. Aye, there’s the point. To die, to sleep—is that all? Aye, all.”

Huh?

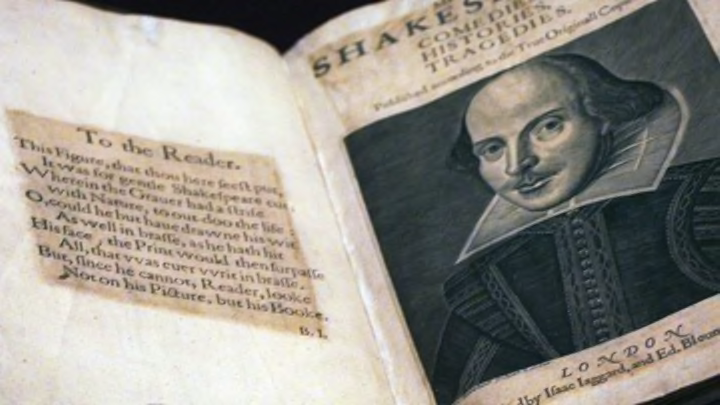

For a full year, from 1603 to 1604, if you went into a bookseller’s shop in London and asked for a copy of The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, to give the play its full name, you’d be given a bound copy of a text that had “Aye, there’s the point” as the totemic speech of the whole play. Today we call that edition a bad quarto, which was eventually replaced by a better good quarto, before the definitive edition of Shakespeare’s plays that we tend to read today—the first folio—was released in 1623 after his death.

What’s gone wrong? Where’s “Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”? What could the world have been like if we hadn’t been gifted Hamlet shuffling off his mortal coil?

It’s quite simple. Just as today pirates walk into cinemas around the world and record movies from the screen to sell as knock-off DVDs before a major release, so back in the 1600s unscrupulous businessmen would walk into the pit at plays and commit an equivalent act of piracy: They’d scribble down what they could remember, go back to their printing presses and put out a version cobbled together from their notes.

If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody

How do we know that plays of the time were reconstructed from memory and issued by booksellers? Well, by a contemporary play, of course. Thomas Heywood was a friend and rival of Shakespeare, writing plays for Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences. One such play was If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody, performed some time around July 1605. In the prologue to the first part, a character in the play utters the following lines:

Your skilless tongue doth make our well-tun’d words Jar in the Prince’s ears; and of our text You make a wrong construction.

The key words there? “And of our text you make a wrong construction.” Heywood’s calling out a character for misconstruing his words, and directly referencing the people turning up to his plays to pirate his text. But as with all things, there are complications.

Of course, scholarship changes, and there’s no way of definitively knowing one way or the other whether a particular text is true to the one Shakespeare intended to be performed. Indeed, nowadays some scholars believe that many texts previously described as bad quartos are in fact just earlier versions of a play, and the so-called good quartos—that is, the ones taken as canon—are composites of one or more earlier versions.

What’s in a phrase?

Romeo and Juliet is one such play where people are no longer so sure about the difference between good and bad. The supposed malignant text was first published in 1597; the good version two years later. For centuries, that was the accepted wisdom. But elements of the bad quarto have made their way into the texts in our classrooms and on our bookshelves: almost all the stage directions we see are from the 1597 quarto, which appears to have been used as an actor’s crib sheet (much abridged and paraphrased, but with the important stage movements a player would need to recall).

Take one of Juliet’s most famous speeches: “What’s in a name?”

The text most of us know goes as follows:

What's Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot, Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part Belonging to a man. O, be some other name! What's in a name? that which we call a rose By any other name would smell as sweet; So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call'd, Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name, And for that name which is no part of thee Take all myself.

But the bad 1597 quarto is slightly shorter:

What’s Montague? It is nor hand nor foote, Nor arme nor face, nor any other part , What’s in a name? That which we call a rose, By any other name would smell as sweet.

Your host and guide

It wasn’t just actors’ versions and audience recall that created our bad quartos: Some actors, likely in Shakespeare’s company, were responsible for some of the texts. We owe the hypothesis of memorial reconstruction being the cause of so-called bad quartos to Sir Walter Wilson Greg. In 1909, aged 34, he sat down with two versions of Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor—one early quarto and the later folio edition (the terms refer to the way in which the texts were printed and bound; a folio page was 12 inches by 15 inches, a quarto 9½ inches by 12 inches). Not only did he find discrepancies between the two versions, but he felt that this version of Shakespeare’s story wasn’t dashed down by groundlings in the audience.

Greg was sure that this quarto edition was pieced together from memory by an actor. In fact, Greg believed that he could pin down which role the actor played. To his eyes, the thespian playing the Host in the play was responsible for the bad quarto—mainly because his scenes were the fullest fleshed out.

Canonical copies

We could well have been performing poor imitations of Shakespeare’s plays were it not for John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s friends and contemporaries. Eighteen bad copies of Shakespeare’s plays were floating around among London’s literati in the seven years after his death in 1616. Heminges and Condell wanted to change that, believing they were bringing down Shakespeare’s reputation as a playwright.

So they mustered together the best and most canonical versions of his plays they could find, often direct from the source, and put them out in a 900-page folio. That folio—with a few changes, thanks to modern scholarship—forms the basis for the texts we know and love today. And we’ve got a lot to thank Heminges and Condell for. Without them we’d be quoting “To be or not to be. Aye, there’s the point.”