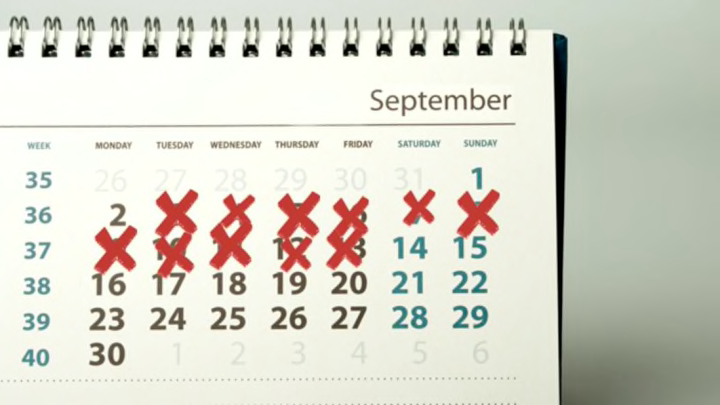

Six and a half million Britons went to bed on September 2, 1752, and woke up on September 14. The reason? The Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750, of course.

Now, your average Brit had as much knowledge of Parliament then as we do of day-to-day life in the 1750s, so this might need a little unpacking. You see, it’s all to do with calendars—the way we tabulate time—and how Britain fell out of sync with the world, and felt the need to catch back up. And what’s more, it goes back 170 years prior to 1752.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII was 10 years into his reign as leader of the Catholic church. He had a problem with Easter. The Julian calendar that the church (and large swaths of the world) used at the time measured a year as 365 days and 6 hours long.

That’s close, but not quite right. The average length of a year is 365 days, 5 hours and 49 minutes. The 11 minutes difference might not seem like all that much, but compounded over 1300 years, it begins to add up. So on February 24, 1582, Pope Gregory XIII released a papal bull—a declaration from the leader of the Catholic church—decreeing that those under the dominionship of his church would have to skip some days. Spain, large parts of Italy (which was not yet unified), the Netherlands, France, Portugal, Luxembourg, and Poland and Lithuania (who were at the time tied under a commonwealth) all adopted Gregory’s bull that year.

Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Hungary, and Prussia all followed in the next 50 years, so that large parts of Europe were now ticking off days on their shiny new Gregorian calendars.

Land of Hope and Glory

Britain (England until 1707) was a holdout. It had a large empire, and enough power to feel like it didn’t immediately need to cop to the Catholic calendar (bear in mind, too, that when Gregory made his switch, England’s church was only 50 years out from a nasty split with the Catholic church). But it all got rather confusing: People often headed up letters they wrote with two dates—one using the new Gregorian calendar in fashion in mainland Europe, and the other using the old-fashioned Julian calendar.

Eventually, Britain capitulated and instigated its Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750. Within the legislation, the government admitted that the old-style calendar had caused “divers inconveniences, not only as it differs from the usage of neighbouring nations, but also from the legal method of computation in Scotland, and from the common usage throughout the whole kingdom, and thereby frequent mistakes are occasioned in the dates of deeds and other writings, and disputes arise therefrom.

“In and throughout all his Majesty’s dominions and countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, belonging or subject to the crown of Great Britain,” the act continued, “the second day of September in the said year one thousand seven hundred and fifty-two inclusive; and that the natural day next immediately following the said second day of September shall be called, reckoned, and accounted to be the fourteenth day of September, omitting for that time only the eleven intermediate nominal days of the common calendar.”

The Final Holdouts

And so, with that act of Parliament, Britain (and its colonies) joined most of the rest of Europe in using the Gregorian calendar. September 3 through September 13 were skipped altogether for 1752, and life went on. Despite what some people say, there was little backlash from the public.

Britain wasn’t the last holdout for the new form of calendar, either—not by a long shot. Russia didn’t change over until 1918. Greece refused to switch until 1923. By then the synchronisation had become so bad that the two countries needed to skip 13 days, rather than 11. It’s one of the only ways that people can skip forward in time until we invent the time machine.