If you’ve studied the writings of John Donne, the 17th-century English poet and priest, you know that many of his verses are filled with sexual innuendo that's masked with religious symbols and imagery. There’s nothing subtle, however, about the socially charged work by Donne recently rediscovered in the archives of Westminster Abbey, according to The Guardian.

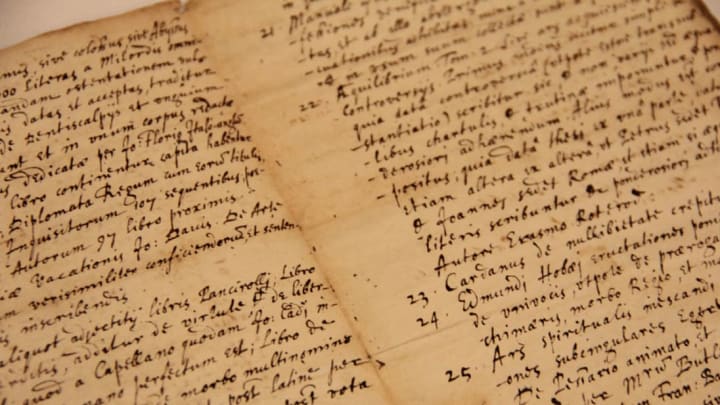

Found buried inside a tin trunk among hundreds of fragments of documents, the handwritten manuscript is the earliest-known copy of Donne’s The Courtier's Library. The mock library catalog satirizes Jacobean England, public figures, and religious corruption, and could have led to the writer’s downfall if it had been seen by anyone aside from his most intimate confidants.

Donne wrote The Courtier’s Library—still a relatively obscure work— in the early 1600s, and this particular copy has been dated back to 1603 to 1604. While not in Donne's own handwriting, the find is important. “It gives us important new clues about the life and writing of one of our most important writers,” said Daniel Starza Smith, a lecturer in early modern English literature at King’s College London, according to a news release.

Matthew Payne, who works as the keeper of documents at Westminster Abbey, found the lost Donne manuscript in fall 2016 while perusing the tin trunk’s unsorted contents. The truck mostly contained fragments of administrative records dating back to the late medieval and early modern period, but amid the mouse-eaten papers Payne found one complete document that had no title or author listed. The work was written in Latin, and with the help of Google, Payne identified it as Donne’s Catalogus Librorum Satiricus, or The Courtier’s Library.

Donne wrote The Courtier’s Library when he was a young, bitter man working as a lawyer to make ends meet and support a growing family. He’d recently lost his title as the secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, England's Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, after he’d secretly marrying Egerton's niece, Anne More. More’s father, a courtier and parliament member, disapproved of the relationship, and when he learned of his daughter's union, Sir George More briefly imprisoned Donne and stripped him of his post.

Donne circulated The Courtier’s Library among his friends and patrons, but didn’t dare to print it during the reign of King James I, when anti-Catholicism was on the rise. (Donne was raised Catholic but eventually converted to Anglicanism.) In addition to poking fun at religion, it made fun of real public officials. One of the scandalous catalog’s imaginary books features "the many confessions of poisoners given to Justice Manwood, and used by him afterwards in wiping his buttocks, and in examining his evacuations.” The manuscript also contains sections called “Ars Spiritualis Inescandi Mulieres" ("The Spiritual Art of Enticing Women"), “On the Nothingness of a Fart,” and “Concerning the method of emptying the dung from Noah’s Ark.”

Nobody quite knows how the early copy of The Courtier’s Library made its way to Westminster Abbey, but experts say its rediscovery is timely, given today’s political climate. “We might think of ‘fake news’ as a modern phenomenon, but Donne saw something similar happening around him,” Smith said. “He was horrified at the corruption of truth by the powerful, greedy, and willfully ignorant, and he responded with this vicious satire, which was too dangerous to print until after his death. This discovery helps us understand how it circulated furtively among his trusted friends.”

An essay describing the find will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Review of English Studies. The manuscript itself will go on display from November 13 to November 18 in St Margaret’s Church, which is next door to Westminster Abbey.

[h/t The Guardian]