The reputation of self-publishing—at least in the pre-internet era—wasn’t that great. There’s a reason that publishing houses catering to non-professional writers were called “vanity presses.” Your stereotypical self-published author was a little old lady with a briefcase full of messy manuscript pages, paying thousands of dollars to produce a poorly proofread doorstop that no one read.

And yet some of the greatest creators of all time have ponied up their own cash to see their works in print. Why? Let’s find out.

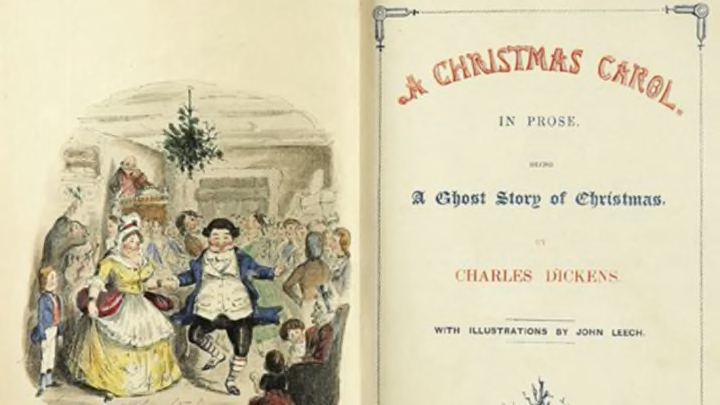

1. A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1843)

Under intense stress (a mortgage payment was due and his wife was expecting), the iconic British author wrote A Christmas Carol in six weeks. But he was frustrated with his publishers, Chapman and Hall, over poor sales of his most recent book, Martin Chuzzlewit, and decided to pay them to print the book—with proceeds going directly to him. Production problems plagued the book, and the whole process cost Dickens more than he expected. Even though the first printing sold out, he only made £137 of an anticipated £1,000.

2. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (1855)

Getty Images

This quintessentially American author didn’t just pay to publish the first edition of Leaves of Grass, his defining poetry collection. He also helped set the type. That first edition was only sold in two stores—one in New York and one in Brooklyn. Several more editions followed, adding many more poems (that first version contained only 12 poems, no titles, and no author’s credit).

3. The Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer (1931)

Newly widowed and staring the Great Depression in the face, Irma Rombauer zigged where others may have zagged. Rather than hunkering down and attempting to survive on some $6000 in savings, she instead put together a collection of recipes. She titled it The Joy of Cooking and had her daughter create a baffling cover illustration (apparently the dragon being slain represents pointless toil in the kitchen). And she spent virtually all of that $6000 to publish the book. Sales of that first edition carried her along until a substantially reworked version was issued by Bobbs-Merrill in 1936 and entered the American mainstream.

4. 114 Songs by Charles Ives (1922)

Ives, a pathbreaking composer (and insurance executive) had no natural place in the sedate world of early 20th-century classical music. But his business success allowed him to compose whatever he wanted, and whenever he saw fit—until the muse deserted him in the early 1920s. As a way to explain himself (and possibly get some performances), he summed up his creative life with this self-published volume. By the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, he was all the rage.

5. Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust (1913)

The Remembrances of Things Past author found no takers for the first volume of his autobiographical masterwork. As a matter of fact, the rejections were stinging: ”My dear fellow, I may be dead from the neck up, but rack my brains as I may I can’t see why a chap should need thirty pages to describe how he turns over in bed before going to sleep,” read one. Proust had money, though, and paid publisher Editions Grasset to print the book. After the first volume was issued, Nobel Prize-winning writer and editor Andre Gide, who had rejected it, saw the error of his ways and published further volumes.