In 1931, P. D. Gwaltney Jr. entered a hotel in Washington, D.C. with a suitcase in his hand and a question on his mind: Could he stow a piece of luggage in the hotel’s vault? The clerk looked at the suitcase and asked what was inside that was so important. Gwaltney’s answer was, in effect, “Oh, just my pet ham.”

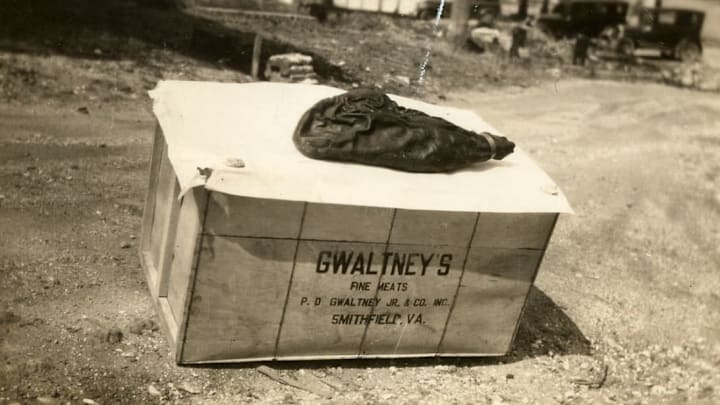

Gwaltney wasn’t joking. He was a ham man, the owner of one of the most successful pork-processing companies in Virginia, and he promoted his business by lugging around a 30-year-old smoked “pet ham,” which he showed off at county fairs, food shows, and even military ships. Much like a dog, it had its own personalized brass collar.

Nor was Gwaltney joking about having the hotel safeguard it. An insurance company valued it at $5000—or $77,000 in today’s money. “Whenever he went to a food show, [Gwaltney] brought a special chain, and he’d bolt the chain to the floor so no one would steal the ham,” Tracey L. Neikirk, curator of the Isle of Wight County Museum in Smithfield, Virginia, told Mental Floss.

It was all part of a clever marketing ploy that had helped cement Gwaltney’s hometown of Smithfield as the Ham Capital of the World.

Virginia Is For (Ham) Lovers

Virginia and hams have gone together since the state was first settled. According to the inimitable The Country Ham Book by Jeanne Voltz and Elaine J. Harvell, when English colonists arrived in Jamestown in 1607, they came with a ship full of pigs. The vessels that followed in their wake also brought swine. Eventually, so many pigs were clogging the footpaths of nearby Williamsburg that locals banished the pigs to an island on the west bank of James River, now called Hog Island.

The pig population flourished around Smithfield and Isle of Wight County. When peanuts became the region’s go-to crop after the Civil War, the pigs were allowed to wander onto the peanut fields and fatten themselves on the leftovers of the year’s harvest. These peanut-stuffed pigs would launch Smithfield and its hams to culinary stardom.

The peanut diet—along with a lengthy curing process—produced a uniquely flavored ham that wowed taste buds across the globe. By the middle of the 19th century, Queen Victoria was ordering six Smithfield hams a week for her palace kitchen. Prices for Smithfield hams soared. When counterfeiters began hawking inferior meat under the same name, the Virginia state legislature created strict rules for what qualified as a Smithfield ham: The pigs had to be fed on a partial diet of peanuts, and the ham had to be cured within the boundaries of Smithfield proper.

In other words, Smithfield had become the Champagne of hams. Enter P. D. Gwaltney Jr.

A Nutty Idea

In 1891, P. D. Gwaltney Jr. joined his father’s Smithfield peanut business and helped expand the company into a ham-making superpower. By this point, Junior had learned a few lessons in marketing from his old man: A year earlier, his father had picked a peanut from a local field, scribbled the year on it, and began showing the well-preserved specimen to anybody curious about the quality of his crop. As years passed, Gwaltney Sr. realized that the peanut’s age was an attraction in itself—today, it’s the oldest peanut in the world.

In 1902, Gwaltney Jr. pulled off a similar stunt when a single cured shank was accidentally forgotten in his warehouse. When he discovered the abandoned ham, Gwaltney smelled a smoking business opportunity. He decided to keep the ham to see how long it could last.

Years passed. In August 1921, one of the Gwaltney family peanut warehouses caught on fire, sending tons of peanuts and a nearby ham-house up in flames. According to the Isle of Wight County Museum, “The smell of burnt peanuts and melting fat hung in the air for weeks.” (Tragedy never smelled so delicious.) The pet ham, safely stowed offsite, was spared.

The fire permanently crippled Smithfield’s peanut business and left ham as the town’s top export. Gwaltney Jr. responded by aggressively promoting his ham products—and that meant trotting out the pet ham. He insured it for $1000, then he upped the protection to $5000. In 1932, the ham appeared in Robert Ripley’s Believe it Or Not (which claimed the ham “remains tender and sweet and fit to eat after 30 years”).

Now, the 123-year-old hunk of meat—officially the world’s oldest ham—is burnt maroon in color, marbled with splotches of yellow and white, and covered with deep wrinkles. It resembles old dried leather. It shares a special glass case with two fellow hams at the Isle of Wight County Museum.

According to Neikirk, the ham smells “smoky” and “woody.” (Its neighbor—the world’s largest ham, which weighs 65 pounds—is more complex: “It still has a thick layer of fat on it, and the fat still has peanut oil in it. So if it gets warm, you can actually smell peanuts.”) And while both hams remain edible, the century-old specimen is not as appetizing as it used to be. “It’s more like ham jerky now,” Neikirk said.

Today, the museum continues the ham’s tasteful history of playful gimmickry. Each year, it holds a “Pan-Ham” competition, asking world travelers to bring a photo of Gwaltney and his ham on their vacations. (Winners are awarded a basket of peanuts.) The ham has an account on X (formerly Twitter). And a webcam allows ham fans around the world the opportunity to check in 24/7.

Discover More Strange Stories:

A version of this story originally ran in 2018; it has been updated for 2025.