According to several of those sites where you can find a holiday for anything, October 3rd is Virus Appreciation Day. Nobody seems to know why this is Virus Appreciation Day, or whose idea is it, or whether they meant computer viruses or the biological cell-invading kind. But hey, it's a holiday, so we will celebrate, well, not viruses, but the success we've had so far in fighting them.

Smallpox virus.

Most viruses are not much to celebrate, but we can celebrate the fact that medical science is fighting them and making a lot of progress. One of the best virus stories is that of smallpox. Smallpox is caused by the Variola virus, and documented human cases go back 3,000 years. Scientists studying viral DNA estimate the disease invaded humans as far back as 10,000 years ago. Smallpox viruses com in two forms, with the more dangerous resulting death to a third of those who contract it. It wasn't a huge problem until people began to settle into crowded cities during the Middle Ages. It then devastated the natives of the Americas, who had no natural immunity, when Europeans arrived in the 1500s.

The value of inoculation was known for hundreds of years, and methods were developed to induce a mild case of smallpox, so the body would develop immunity. It wasn't perfect, and people still died. Dr. Edward Jenner knew that milkmaids who had suffered cowpox were immune to smallpox, so in 1796 he introduced pus from a cowpox-infected milkmaid to the body of eight-year-old James Phipps. Phipps was not the first to be inoculated with cowpox in hopes of smallpox protection, but Phipps was later exposed to smallpox (by Jenner) several time and his immune system fought it off.

An 1802 cartoon makes a joke of cowpox inoculation.

The World Health Organization announced an initiative in 1967 to eradicate smallpox from the entire world. The vaccine, which had been steadily improved since Jenner's day, was sent everywhere to inoculate children and adults. Ten years later, smallpox could not be found in the natural world. Only two research repositories remain, one in Atlanta, the other in Russia.

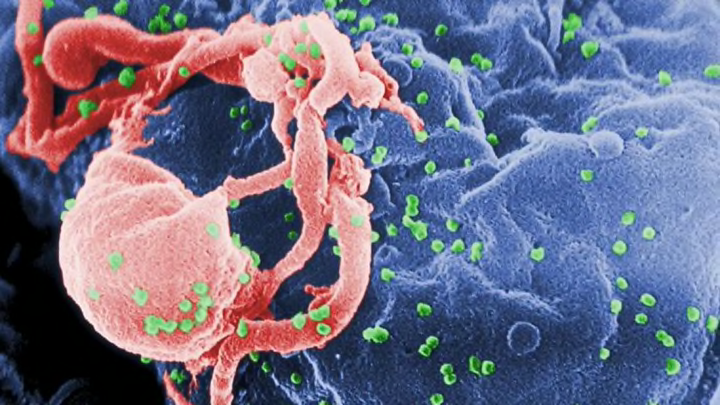

HIV, in green, attacking a lymphocyte. Image by C. Goldsmith.

The world felt pretty good about vaccines against viruses, but in the 1980s, we got a wakeup call. A new and deadly diseases that was eventually called AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) was found to be growing in certain populations in which the virus transferred from person to person. It is caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV. The presence of HIV suppresses the body's immune system (particularly a white cell type known as T-cells), allowing any common infection to become life-threatening.

An HIV infected T-cell. Photograph by Flickr user NIAID.

The virus is transmitted by body fluids in close contact, as in sex, sharing needles among drug addicts, childbirth, and in blood transfusions. In addition, the fact that it was initially most prevalent in the gay community in America stigmatized the disease's victims and politicized the fight against it. The lethality of the disease terrified people, no matter how difficult it is to become infected. In the thirty years since we became aware of AIDS, retroviral therapy has helped those infected with HIV to keep from developing AIDS, and safe sex education has popularized the use of condoms for prevention against contracting the virus. However, there is still no effective vaccine or cure for AIDS.

Common polio virus.

Just last week, I posted a story and said, "And we wondered for so long if viruses served any purpose." It was about the trials of Fritz Anderson, who was diagnosed with a deadly brain tumor that did not respond to surgery or chemotherapy. Then he enrolled in an experiment involving a genetically-engineered polio virus that is deadly to cancer cells and does not invade healthy brain tissue. Anderson's skull was opened and the virus was infused into his exposed brain. Two years later, Anderson's tumor appears as only a shadow in his brain. Perhaps viruses are good for something after all.