Scientists have developed a new way to cut off the blood flow to cancerous tumors, causing them to eventually shrivel up and die. As Business Insider reports, the new treatment uses a design inspired by origami to infiltrate crucial blood vessels while leaving the rest of the body unharmed.

A team of molecular chemists from Arizona State University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences describe their method in the journal Nature Biotechnology. First, they constructed robots that are 1000 times smaller than a human hair from strands of DNA. These tiny devices contain enzymes called thrombin that encourage blood clotting, and they're rolled up tightly enough to keep the substance contained.

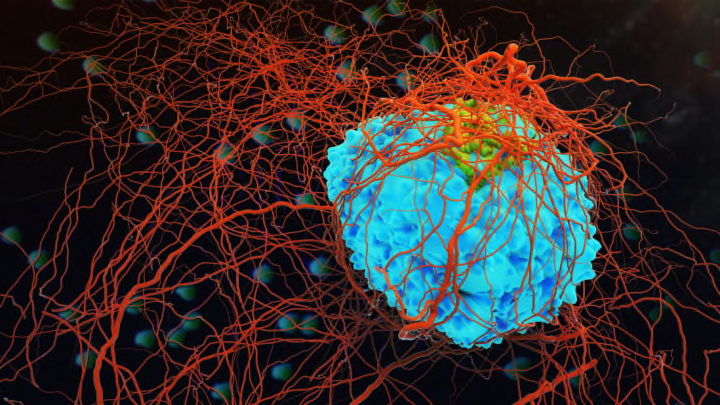

Next, researchers injected the robots into the bloodstreams of mice and small pigs sick with different types of cancer. The DNA sought the tumor in the body while leaving healthy cells alone. The robot knew when it reached the tumor and responded by unfurling and releasing the thrombin into the blood vessel that fed it. A clot started to form, eventually blocking off the tumor's blood supply and causing the cancerous tissues to die.

The treatment has been tested on dozen of animals with breast, lung, skin, and ovarian cancers. In mice, the average life expectancy doubled, and in three of the skin cancer cases tumors regressed completely.

Researchers are optimistic about the therapy's effectiveness on cancers throughout the body. There's not much variation between the blood vessels that supply tumors, whether they're in an ovary in or a prostate. So if triggering a blood clot causes one type of tumor to waste away, the same method holds promise for other cancers.

But before the scientists think too far ahead, they'll need to test the treatments on human patients. Nanobots have been an appealing cancer-fighting option to researchers for years. If effective, the machines can target cancer at the microscopic level without causing harm to healthy cells. But if something goes wrong, the bots could end up attacking the wrong tissue and leave the patient worse off. Study co-author Hao Yan believes this latest method may be the one that gets it right. He said in a statement, "I think we are much closer to real, practical medical applications of the technology."

[h/t Business Insider]