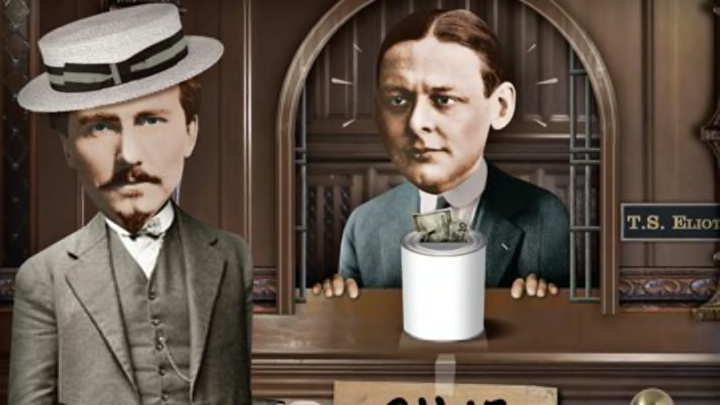

T.S. Eliot was poised to be the top poet of his generation. But first he had to be rescued from his day job.

In 1921, suffering from a “nervous disorder,” T.S. Eliot took a three-month hiatus from his day job. The 33-year-old had been working as a clerk in the London sub-basement of Lloyds Bank for four years. But with the luxury of time, the part-time poet focused his attention on completing his magnum opus, “The Waste Land.”

Released in 1922, Eliot’s haunting and defiantly oblique work is a landmark of modernism; even at its most impenetrable, one reviewer admitted that Eliot’s work possessed “the music of ideas.” Ezra Pound, too, was impressed. Convinced of Eliot’s genius, Pound reckoned that the grunt work was smothering his creativity. “Some of us consider Eliot’s employment in a bank the worst waste in contemporary literature,” Pound bemoaned.

Of course, financing poetry is a problem as old as poetry itself. For Emily Dickinson or Lord Byron, the answer was simple—being born into the right family relieved them of the worry. Others turned to hack writing to stock the till. Walt Whitman penned a temperance tract while guzzling cheap wine. Edgar Allan Poe cranked out newspaper filler like “Why Not Try a Mineralized Pavement?” When William Wordsworth landed a decidedly unromantic job as a tax collector, he could take comfort in the knowledge that Geoffrey Chaucer had been a customs comptroller in the 14th century. “There’s no money in poetry,” Robert Graves once observed, “but then there’s no poetry in money either.”

Pound was out to change that. He wanted to help Eliot write for a living instead of squandering his talents at the bank, but he was skeptical that members of high society would open their purses for such edgy writing. “We can’t expect illiterate, newly rich millionaires to pay for things they have not the taste to enjoy,” he scoffed. Instead, he hatched a revolutionary plan to crowdsource a fund for Eliot.

He dubbed his campaign Bel Esprit and started by drawing up a brochure. In it, he asked “subscribers” to pledge about $50 a year. The goal was to support Eliot for five years at $1,500 a year—the bare minimum he’d need to quit his job and do nothing but write.

Pound proved to be an ideal fundraiser.

An opinionated and fiery poet, the Ph.D. dropout (who sometimes wore a sombrero over his wild red hair) was a tireless advocate for fellow artists. And he was quick to stress that his plan was not charity. “I can’t come back too STRONGLY to the point that I do NOT consider this Eliot subsidy a pension,” he wrote to one donor. “I am puke sick of the idea of pensions, taking care of old crocks. ... I put this money into him, as I wd. put into a shoe factory if I wanted shoes.” To Pound, Bel Esprit was an investment in poetry, and he expected it to yield dividends to all humanity. He wasn’t the only one. Pound managed to convince a number of artist friends—including the poet William Carlos Williams, himself working a day job as a New Jersey pediatrician—to pledge. Ernest Hemingway, too, helped raise funds but then blew the cash at a racetrack.

Things were progressing nicely until Pound’s plan hit a major snag. It turned out that Eliot didn’t want to quit his job! He liked being employed by the bank and actually took pleasure in his work.

Pound should have seen this coming. Aldous Huxley once declared Eliot “the most bank-clerky of all bank clerks.” Virginia Woolf joked that he was so stiff and buttoned up that he’d attend informal lunches “in a four-piece suit.” Not only did Eliot appreciate the steady paycheck, but Lloyds meant a solid pension for him and his ailing wife, Vivienne. She, too, didn’t want him to quit. “If he did take such steps,” Vivienne warned, “I should bear him a considerable grudge.”

Still, Eliot wasn’t averse to support—at least, until the plan leaked to The Liverpool Post, which falsely claimed that he’d already taken the donations and ungratefully kept his job anyway. The Chicago Daily Tribune and The New York Tribune picked up the story, with the latter mocking that “To coddle an author is to reduce him to the level of a Pekingese.”

Eliot was mortified. Fearful for his Lloyds job, he demanded a retraction from The Liverpool Post. The paper complied.

History generally has Bel Esprit dying there—but in fact, Pound hadn’t quite given up. He removed Eliot’s name but still stumped for Bel Esprit to Poetry magazine and The New York Times. When an Ohio high school English teacher inquired about it in August 1923, Pound still sounded hopeful that Eliot would accept the funds. And later that year, he did: two installments amounting to about $550 found their way into his account. Soon thereafter, Pound dropped out of sight, and with him, all plans for Bel Esprit vanished too.

As it turned out, Eliot didn’t need Bel Esprit. In 1925, he left Lloyds—“the prospect of staying there for the rest of my life is abominable to me,” he conceded—to take a job as an editor at a publishing house. Pound’s faith in him would be amply confirmed when the former bank clerk won a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948.

Perhaps the Bel Esprit plan was simply ahead of its time. Today, websites like Kickstarter fund poets' dreams by cold-calling the masses, treating each donation as an investment. One recent appeal for the Line Assembly Poetry Tour and Documentary mustered $18,888 on the slogan “Six poets. One van. No quit.” Ezra Pound would certainly approve.