The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 96th installment in the series.

December 23, 1913: France Sends Anti-German Ambassador to Russia, Federal Reserve Created

Aside from the foreign minister, the most important job in the French diplomatic universe was ambassador to Russia. As guardian of the sacred Franco-Russian Alliance, the French minister to St. Petersburg was responsible for shoring up the key pillar of French national security, which meant reassuring the Russians of French commitment while politely extracting more concrete guarantees from the Russians.

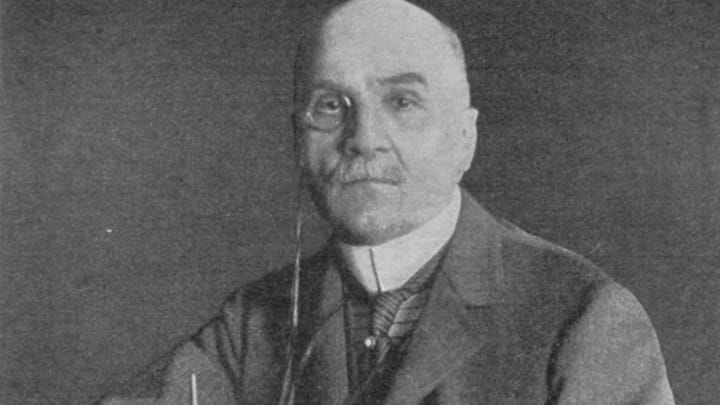

The appointment of Theophile Delcassé as ambassador to the court of the Tsar in February 1913 sent a clear message to friend and foe alike. A former foreign minister and one of the main architects of the Franco-Russian Alliance, Delcassé was convinced that France was on a collision course with Germany, leading Kaiser Wilhelm II to call him “the most dangerous man for Germany in France.” Before leaving for Russia Delcassé told Maurice Paléologue (top), the foreign ministry’s (also ferociously “anti-German”) political director: “We are inevitably headed toward a great European conflict, and it will be France which will bear the first blow… for make no mistake about it, Germany will attack us through Belgium… It is necessary, therefore, that the Russian ally be in such a state to be able to launch a full-scale offensive in the shortest possible time…”

Over the course of 1913, Delcassé (along with French commander-in-chief Joseph Joffre and President Raymond Poincaré) firmed up the Russian alliance, resulting in a new military convention, signed in September 1913, confirming and elaborating their plans for near-simultaneous attacks on Germany; this included a personal promise from Tsar Nicholas II to invade East Prussia within 15 days of mobilization (M+15) in hopes of forcing the Germans to divert forces from their attack on France.

But in the winter of 1913 Delcassé, complaining of ill health (and nursing political ambitions back home) let it be known that he would like to return to France. Opportunistic as always, on December 23, 1913, Poincaré seized the chance to cement his control over French foreign policy by nominating his friend Paléologue to replace Delcassé in St. Petersburg—thus sending someone who was perhaps even more virulently anti-German than Delcassé, if that were possible, to represent the Republic in Russia.

Paléologue’s appointment was especially significant in the context of the continuing Liman von Sanders Affair, which the Russians viewed as a test of French solidarity in the face of German bullying. President Poincaré had previously hinted he might support Russia’s claims to control the Ottoman capital Constantinople and the Turkish straits, and Paléologue—whose family claimed (probably spurious) descent from Byzantine emperors—would support Russian claims to the ancient city in the coming conflict, helping pave the way for the disastrous Gallipoli Expedition.

Paléologue’s appointment further consolidated the Franco-Russian Alliance during the final countdown to war, as both partners signaled their determination not to tolerate German bullying, relying on their mutual defensive agreement for strength. Bidding farewell to Paléologue in January 1914, French Prime Minister Gaston Doumergue left no doubt about the main thrust of his mission to St. Petersburg: “War can break out from one day to the next… Our allies must rush to our aid.” Meanwhile, Tsar Nicholas II echoed Poincaré’s earlier calls for a firm line against Germany, warning the departing Delcassé, “We shall not let ourselves be trampled upon.”

Federal Reserve Created

On December 23, 1913, Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act, creating a new national bank and massively increasing the government’s power to intervene in the economy by setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money.

The United States had had national banks before: In 1791, Congress chartered the First Bank of the United States at the urging of Alexander Hamilton, who wanted the federal government to assume the Revolutionary War debts of the states to stabilize their finances and foster adherence to the new nation. But the national bank faced fierce opposition from Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and other critics who feared official corruption and federal aggrandizement. In 1833, Andrew Jackson shut down the Second Bank of the United States (the successor institution chartered in 1816), which he accused of favoring northeastern industrial interests over small farmers on the frontier. To “democratize” the financial system Jackson transferred the national bank’s funds to state banks (“pet banks”) mostly selected for political loyalty to Jackson and his allies in the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, “wildcat” banks free from federal regulation sprang up around the country and began issuing huge amounts of bank notes with little or no backing, resulting in financial collapse and the Depression of 1837.

During the Civil War, Congress created a new system of “national banks” to finance the war and introduce the first uniform national currency, but stopped short of creating a new central bank, so the new national banks (which mostly operated like state banks) lacked the backing of a “lender of last resort” to supply emergency funds in the event of a financial crisis. That’s what happened in 1907, when a failed attempt to corner the stock of the United Copper Company on Wall Street triggered financial panic and bank runs across the U.S. Total financial collapse was averted by the frantic efforts of J.P. Morgan and bank presidents, essentially acting as an improvised central bank, but the public’s confidence was badly shaken and a steep economic downturn ensued.

The Panic of 1907 laid the groundwork for the formation of the Federal Reserve System, beginning with the creation of a National Monetary Commission in 1908, followed by a top-secret meeting of bankers hosted by Delaware Senator Nelson W. Aldrich and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury A.P. Andrew at Jekyll Island, Georgia, in 1910, where they agreed on an outline for a National Reserve Bank. In January 1911 the National Monetary Commission formally recommended the formation of a National Reserve. After two years of debate over the balance between political and private control, the bill to create the Federal Reserve System – composed of regional Federal Reserve Banks owned by private banks, supervised by an independent Board of Governors, and backed by the “full faith and credit” of the United States—was introduced in the House of Representatives on August 29, 1913, passed by the Senate on December 18, approved by a joint conference committee on December 22 and 23, and immediately signed by President Wilson on the latter date.

During the First World War, the Federal Reserve helped protect the U.S. and world financial system from the initial shocks of the war, then became a key financier of the U.S. and Allied war efforts, with the New York Fed leading the way. To facilitate this process in 1916 and 1917, Congress lowered the amount of “real” money the Fed had to hold as collateral for loans, and also changed the rules so government debt could serve as collateral; this helped increase the money supply to fund the war effort, but also resulted in major inflation, with the purchasing value of the dollar decreasing by roughly half from 1914 and 1920. After the war the Fed’s “easy money” policies helped fuel the economic expansion of the “Roaring 20s,” but also contributed to the credit bubble that finally popped in 1929, triggering the Great Depression.

See the previous installment or all entries.