In The Royal Art of Poison: Filthy Palaces, Fatal Cosmetics, Deadly Medicine, and Murder Most Foul, author Eleanor Herman delves into the deadly—and often disgusting—world that lay beneath Western Europe's most glittering palaces. From the gut-roiling poisons used to dispatch enemies and inconvenient heirs to the methods the highest-born unknowingly used to poison themselves (think mercury enemas and lead cosmetics), it's a book that will make you think twice the next time you admire a royal portrait. Along the way, Herman analyzes the suspicious deaths of some of the most famous people in European history—deaths in which poison may have played a part. Read on for an excerpt about Tycho Brahe, possibly one of the most eccentric astronomers in history.

When the world’s greatest astronomer, the colorful Tycho Brahe, sat down to a hearty banquet at a neighboring nobleman’s house in Prague on October 13, 1601, he must have looked forward to a convivial night of wine, food, charming women, and witty conversation, all of which this fun-loving Dane enjoyed in great measure. Brahe was a jolly soul with an eccentric, extroverted personality. Known to his contemporaries as a “man of easy fellowship,” he “did not hold anger and offense, but was ever ready to forgive.”

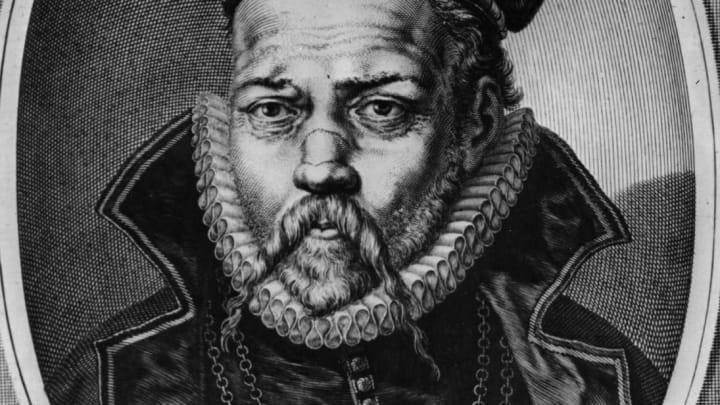

Red-haired, blue-eyed, and sporting a trim pointed beard and handlebar mustache, the astronomer wore a metal nose reported to be either gold or silver, as he had lost the bridge of his nose at the age of twenty in a duel over a mathematical formula. When the glue holding his nose in place came loose, he would remove the prosthesis, take a bottle of glue out of his pocket, and glue it back on.

Brahe’s eccentricities were widely known. He had a dwarf jester named Jepp with supposed psychic abilities, who sat under his dining room table during meals. For years, Brahe kept a beer-swigging pet elk in his castle. One night the elk drank too much beer, fell down a staircase and died. It is not known if Jepp predicted this.

Noble banquets offered delicious food, fine wine, beautiful music, a glittering table, and fascinating conversation. But there was one down side. They went on for hours, during which time guests were expected to eat and drink until they nearly popped. It was bad etiquette to excuse yourself to use a chamber pot.

As candlelight flickered on golden cups and silver plates, and laughter wafted around him, Brahe felt increasing abdominal discomfort. He must have thought he would be fine once he got home, which was just across the street. After all, the robust 54-year-old Dane had never known any serious illness in his life. By the time he arrived home, the need to relieve his bladder was agonizing. Grunting with relief, he dropped his britches and … nothing. Not a drop. And so began a 400-year-old mystery of jealousy, theft, and possible poison.

Brahe’s fascination with the heavens began in 1560, when, at 14, he witnessed a solar eclipse. He began staying up all night to record astronomical observations. In 1563, he observed a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn and realized that the revered astronomical tables used to predict the event were incorrect. By the time he was in his twenties, his observations had shattered two thousand years of astronomical theory.

In 1599, Brahe became the Imperial Court Astronomer to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Soon after, he hired a new assistant, a 28-year-old German named Johannes Kepler. Though he was an excellent mathematician, Kepler suffered severe hypochondria and violent mood swings. He took the position with Brahe to obtain access to his employer’s 40 years of observations to prove his own astronomical theories—that the universe itself was an image of God, with the Sun corresponding to the Father, the stellar sphere to the Son, and the intervening space to the Holy Ghost. But Brahe, whose work had been plagiarized years earlier by a visitor to his home, refused to give Kepler more than a few observations at a time. Kepler began throwing temper tantrums so epic that Brahe described him as “a rabid dog.” But he didn’t fire him. Perhaps he needed his mathematical abilities.

When Brahe came home from his last banquet, he was in agony, unable to urinate, his belly distended, and feverish. For the next 10 days, pain radiated throughout his body. At times, he was delirious. He died on October 24, 1601.

The strange death of this renowned astronomer caused many to suspect poison. And if Brahe had been poisoned, it must have been the jealous, vicious Kepler, who had carted the 40 years of observations out of Brahe’s house while the grieving family was making funeral arrangements.

Indeed, freed from Brahe’s shadow and armed with his records, Kepler finally achieved the fame he had always desired. He theorized that the planets’ orbits were elliptical, not circular, as had always been believed. He also developed the notion that the sun pulled the planets around by something like magnetic tendrils, a force growing stronger as the planets got closer and weaker as they moved away—breathtakingly close to the theory of gravitational attraction, which Isaac Newton would formulate in 1687 using Kepler’s work.

In 1901, researchers in Prague opened up Tycho’s tomb as part of their celebrations commemorating the 300th anniversary of his death. They found a 5-foot-6-inch skeleton in a fine silk shirt, wool stockings, silk shoes, and a hat, and a crescent-shaped injury on the bridge of the nose, the exact same place where Brahe had been maimed in his youthful duel. Researchers removed hairs from the mustache. In 1991, tests conducted on the hair by the University of Copenhagen’s Institute of Forensic Medicine indicated he had, indeed, been poisoned by mercury, which can shut down the kidneys.

But even science is fallible. Given the sensational stories of Tycho Brahe’s poisoning, a team of Danish and Czech scientists exhumed him again in 2010 and took hair directly from his remains. In a stunning reversal of the 1990s findings, the new results showed that Tycho had not consumed excessive amounts of mercury.

So what did kill him? Most likely benign prostatic hyperplasia, known as BPH, an enlarged prostate gland. This gland surrounds the urethra, the tube through which urine flows. As the prostate grows, it can squeeze the urethra, making it difficult and even impossible to urinate. Left untreated, it can prove fatal.

Johannes Kepler is off the hook. He was a thief, to be sure, but no murderer. Though he had succeeded in attaining the fame he always wanted, happiness and health eluded him. At the age of 58, he developed a fever and, speechless in his final delirium, kept pointing from his forehead to the heavens. The night he died, meteors streaked across the sky.

From The Royal Art of Poison by Eleanor Herman. Copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.