In this series, Mental Floss will examine the engineering problems associated with humanity’s most extreme endeavors, from mining asteroids to colonizing the ocean, and explain how engineers plan to solve them.

“Now would I give a thousand furlongs of sea for an / acre of barren ground, long heath, brown furze, any / thing. The wills above be done! but I would fain / die a dry death.” —William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act I Scene I.

If we’re going to colonize Mars, we’re going to have to deal with the Ghoul. See, we idle dreamers love to talk about how humanity could build that colony on the fourth rock, and how we’d handle the water situation and electricity and so on, but we’re glossing over the hardest part of the whole operation—an operation, it should be noted, that’s nothing but hard parts.

Getting something to Mars and landing it there is basically impossible. You might think it’s just a matter of building a rocket and pointing it in the right direction, and you’d be right, technically, but the men and women who have to actually carry the one and do the hard math know that there’s a dark power at work that often trumps our greatest engineering achievements. There’s no sense in dancing around the issue. There is a giant space monster that doesn’t want us on Mars.

Beating the Mars Curse

Well, not literally. But humans have been sending things to (or near) Mars since 1960, and in that time there have been an inordinate number of accidents. Sometimes we’ve lost contact with our probes. Sometimes they just crash into the planet. Sometimes they never even make it out of Earth’s orbit. Scientists sometimes attribute our weird misfortune to the Great Galactic Ghoul—also called the Mars Curse. The Red Planet, it seems, is located in the stellar equivalent of the Bermuda Triangle.

Monster or no, the challenge here is that colonizing Mars isn’t a one-and-done kind of mission. Multiple ships will need to be sent to Mars, each carrying initial colonization supplies and equipment. Then you’ve got ships carrying people. And once we’re on the ground and building New Schiaparelli (or whatever they call it), it’s not like our space invaders can just slash a few Martian forests for timber, or hunt zitidars for food. Everything they eat (but for what is grown in colonial greenhouses) will need to be shipped Planet Express; likewise, every atom of needed gear. As of today, 23 out of 41 Mars missions have ended in failure. It’s not overstating things to say that a Martian colony will need a success rate at least greater than 50 percent. (After that second rocket transporting food or soap crashes in a row, you can imagine that nerves will be thin on the ground.)

The Need for Faster Spacecraft

About those missions. Right now it takes an average of six months to send something to Mars. As we discussed in the last entry, human beings—weak sacks of bones and goo that we are—don’t really thrive in zero gravity, where we suffer a 1 percent loss of bone density per month. If we want colonists capable of strutting around on their wild new real estate venture (as opposed to wobbling on JPL-emblazoned canes), scientists and engineers have to do one of two things: 1. Breed a race of superhumans to colonize Mars (this didn’t work in that most excellent early-'90s cartoon Exosquad, which totally needs to be remade stat, or at least released on Netflix, my God), or 2. Build a faster spacecraft.

Scientists seem to have chosen the latter of the two choices. Using fusion rockets, a round trip could be cut to 30 days. (By way of comparison, the voyage of the Jamestown colonists in 1607 lasted four and a half months.) We’re probably 20 years away from making them happen, but we’re really close—and not in a flying cars kind of way, but in an honest-to-goodness Oculus Rift/Lawnmower Man way.

NASA's Innovative Advanced Concepts Program has been partially funding a joint MSNW-University of Washington project that would use a magnetic field to compress a certain type of plasma into a fusion state. (Remedial physics: Fission = splitting atoms. Fusion = merging atoms.) In short, magnetic fields would crush metal rings around deuterium-tritium plasma, initiating a fusion reaction. The heated, ionized shell would in turn be shot out of rockets, generating thrust and accelerating a craft to somewhere around 200,000 miles per hour.

All that’s left is to actually do it. The UW scientists have tested each of the various stages of their fusion rocket. The next step is to combine them. Impossible? Nah, these days kids are building fusion reactors in their parents’ garages.

Nailing the Landing

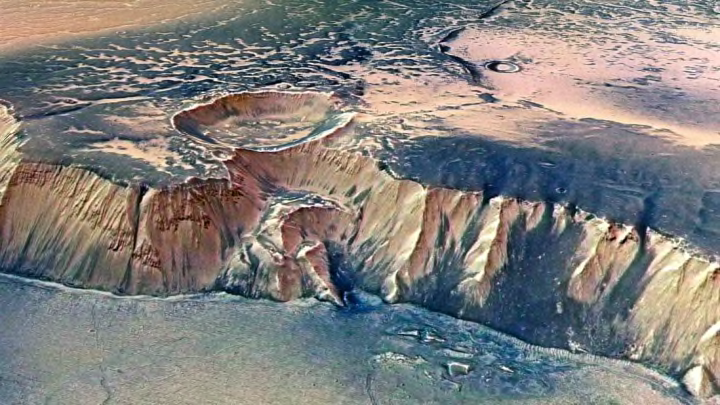

For sake of moving along the discussion, let’s say the ghoul hasn’t managed to swat down our ships on the way to Mars. How do you then land something there, anyway? Let’s use the most recent and audacious example. When NASA landed the rover Curiosity on Mars, they released a video called "7 Minutes of Terror" outlining the difficulties. (The video itself was named for the harrowing length of time it takes to set something on red soil.) The Martian atmosphere is extremely thin—100 times less than that of Earth. There’s enough atmosphere to muddy up the physics of a landing, but not enough that it can sustain the landing of something with parachutes alone.

When the Curiosity craft meteored into the Martian atmosphere, it was traveling at 13,000 miles per hour. (The goal: 0 mph and a soft landing.) Once the craft passed through the atmosphere it was still moving at a speedy 1000 mph, at which point a supersonic parachute deployed with 65,000 lbs. of force. But wait—there’s more.

Temperatures on entry reached 1600 degrees, which is like New Orleans in July. A heat shield protected the craft, but, no longer needed, had to be ejected in order for the radar to see the ground. (“So the computer was flying blind at 13,000 miles per hour?” you ask. Yes!) By now—and remember all of this is happening in seven minutes on another planet—the parachute had slowed the craft to 200 mph. Here’s where things get crazy.

Next, the payload was ejected and sent into a freefall until the rockets could activate. Why? To get the rover away from the vestigial parachute. The rockets then brought everything into a slow vertical descent. The interesting problem here is that the 2000-pound Curiosity is a delicate piece of machinery, and the rockets couldn’t just land the thing, as the boosters would kick up dust and debris, damaging sensors. The solution? A sky crane, which is exactly what it sounds like. Twenty meters from the ground, Curiosity was lowered on a 21-foot tether and then gently set on the surface of another planet tens of millions of miles away.

Final problem: What do you do with those rockets? The landing system cut the tether, and the rockets blasted away from the landing site to keep them from destroying the rover. Adam Steltzner, an Entry/Descent/Landing engineer at JPL, said of the successful plan: “It looks crazy… it is the result of reasoned engineering, but it still looks crazy.”

Sky cranes aren’t expected to be part of the normal rotation because of the high chance of failure, and because a lot of the things we send to Mars aren’t as fragile as a rolling science lab, or as heavy. The svelte rovers Spirit and Opportunity used parachutes, retrorockets, and airbags to land, for example. (The Mars 2020 rover will use a sky crane.) But the Curiosity landing is a good example of how crazy brilliant our engineers are, and how fearless you have to be to put something on a planet that is (averaged) 140 million miles away.

In short, it can be done, but man it’s not easy. Now that we’ve traveled to Mars and have boots on the ground, in the next entry we’ll look at how engineers plan to build sustainable colonies—and why it has to be a one-way mission.