For years, every time we so much as touch a toe out of state, I’ve put cemeteries on our travel itinerary. From garden-like expanses to overgrown boot hills, whether they’re the final resting places of the well-known but not that important or the important but not that well-known, I love them all. After realizing that there are a lot of taphophiles (cemetery and/or tombstone enthusiasts) out there, I’m finally putting my archive of interesting tombstones to good use.

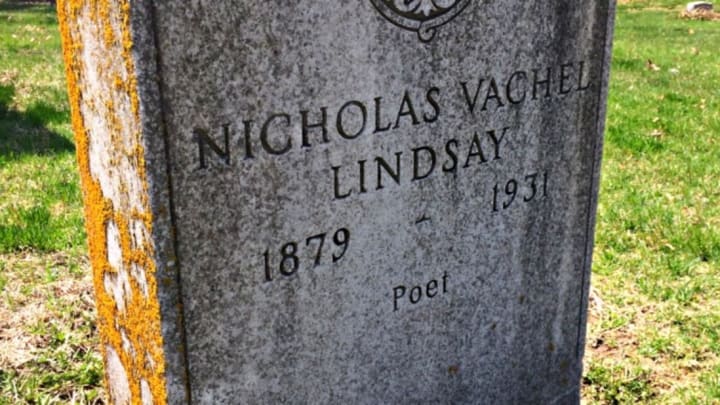

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay was one of the most celebrated poets of the early 20th century. Known as the "Prairie Troubadour" for his sing-songy rhythms with midwestern themes, Lindsay is considered the father of singing poetry. But he didn’t start his career that way.

Though he originally went to school to be a doctor, Lindsay quickly realized that career “choice” was more for his mother and physician father than for himself. After three years of medical studies at Hiram College in Ohio, Lindsay told his parents his heart wasn’t in it. He enrolled at the Chicago Art Institute for two years, then headed to the New York School of Art. It was there that instructor Robert Henri suggested that Lindsay’s artistry would be better expressed in words than in paint.

Taking this advice to heart, young Vachel began selling his poetry on street corners in NYC, then expanded to the whole countryside, wandering on foot and sometimes by steamer or train. He gave lectures and performances, found time to (unsuccessfully) court fellow poet Sara Teasdale, and, oh yeah—wrote a lot of poetry. Traveling seemed to agree with Lindsay, as he wrote some of his best-known pieces while on the road, including "The Congo" and "General William Booth Enters Into Heaven." Born in Springfield, Illinois, Lindsay also found inspiration in the town's most famous son, Abraham Lincoln. Tributes include “Lincoln” and “Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight.”

Despite his success, things began to go downhill for Lindsay sometime around 1922, when his mother died. The following year, he had to endure two sinus surgeries, so he accepted a teaching position that would help him recover and pay for his medical costs. By the time he married in 1925 and had two children shortly thereafter, the popularity and sales of his poetry had declined greatly, and he was having trouble supporting his family. In 1929, he moved them to his old Springfield homestead.

On December 5, 1931, struggling mentally, physically, and financially, Lindsay decided to end it all. After an argument with his wife, he grabbed a bottle of Lysol, locked himself in the bathroom, and poured himself teacup after teacup of the solution until the bottle was emptied. He was crawling upstairs on his hands and knees when his wife found him. “I took Lysol,” he admitted. “They tried to get me; I got them first.” Those cryptic words were his last. Though Mrs. Lindsay called for the doctor, the Prairie Troubadour was dead before help could arrive. Rather than alert the world to Lindsay’s troubling suicide, his doctor decided the death should be reported as heart failure.

Lindsay was buried with his parents at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, the same final resting place as Abraham Lincoln.