One day at the end of May, 1841, William Trailor hopped into a one-horse buggy and began the long journey to Springfield, Illinois, where he planned to reunite with his brothers Henry and Archibald. Joining him was his friend and housemate, a handyman named Archibald Fisher.

In Springfield, the men decided to go for a walk after lunch. But as the afternoon wore on, the brothers somehow lost sight of Fisher. When they returned to Archibald's Springfield home for supper, Fisher wasn't there. The brothers looked briefly for Fischer, but may have assumed he was still out enjoying himself.

But when Fisher failed to show up the next morning, the brothers began to feel uneasy. They spent the day in a fruitless search for the missing man. The same was true of the following day. William eventually left Springfield without him.

According to the local postmaster, rumors circulated that Fisher had died and left William with a large sum of money. True or not, the local postmaster knew about William's trip to Springfield and alerted the postmaster in that city of a possible crime. News of the missing man (and William’s supposed financial windfall) quickly spread.

Within days, all of the Trailor brothers would be arrested—charged with the disappearance and murder of Archibald Fisher.

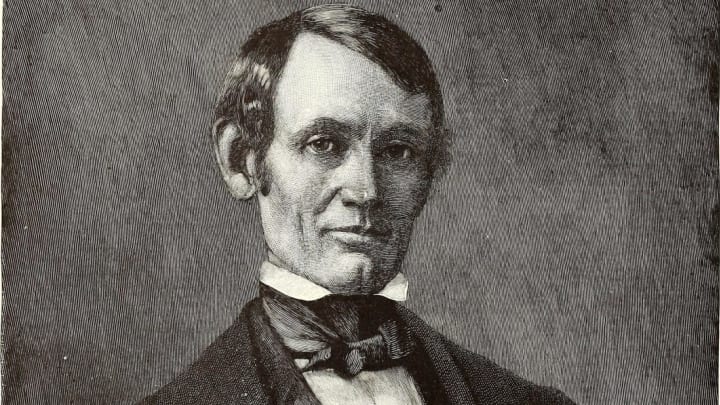

Nobody could find the body. “Examinations were made of cellars, wells, and pits of all descriptions, where it was thought possible the body might be concealed,” wrote Abraham Lincoln, then a young defense lawyer in Springfield. “All the fresh, or tolerably fresh, graves at the grave-yard were pried into, and dead horses and dead dogs were disinterred.”

As locals searched for Fisher’s corpse, both Springfield’s mayor and the Illinois state attorney general ruthlessly interrogated Henry Trailor. For three days, Henry maintained his innocence. But he also began to show signs of cracking. “The prosecutors reminded him that the evidence against him and his two brothers was overwhelming, that they would certainly be hanged,” William H. Townsend wrote in the American Bar Association Journal in 1933, “and that the only chance to save his own life was to become a witness for the State.”

With that bait, Henry confessed: He claimed that his brothers, Archibald and William, had clubbed Fisher to death and had taken all of his money. Henry insisted that he had taken no part in the murder. Rather, he had simply helped his brothers dump the body in the woods.

News of Henry’s confession ignited the public's curiosity, prompting hundreds of people to rush to the forest where Fisher’s body was reportedly hidden. “The story related by Henry Trailor aroused the most intense public indignation, and the murder became almost the sole topic of conversation,” Townsend wrote. “Business was practically suspended as searching parties and amateur detectives scoured the woods and by-ways.”

There, in a dense thicket, investigators found buggy tracks and signs that something large had been dragged through the grass. A nearby pond was partially drained and a dam destroyed, despite protests from the dam's owner. Yet the body continued to elude investigators. The public became antsy.

“It was generally conceded that only a speedy trial and swift punishment could allay the clamor of the populace for the blood of the prisoners and avert the disgrace of a lynching,” Townsend wrote. By June 18, the murder trial had already begun—and a conviction seemed assured.

The courtroom, muggy from the summer humidity, was packed with spectators. Called to the stand, Henry Trailor repeated his confession, claiming that he had helped dispose of Fisher's body. Additional evidence was provided by a local woman who had seen two of the Trailor boys walk into the woods with Fisher—only to see them return alone. Furthermore, investigators claimed they had found human hair in the area near the buggy tracks. The tracks themselves, they noted, had led suspiciously to the pond, as if somebody had tried to dump something.

When the prosecutor rested his case, it seemed like there was no hope for the Trailor brothers.

But the defense had a secret weapon—a 32-year-old lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. The future president calmly stood up and called his one and only witness to the stand.

Dr. Robert Gilmore was a widely respected physician in those parts of Illinois. Sitting in the sauna-like courtroom, the doctor patiently explained that he knew Archibald Fisher well—the man had twice lived in his home. Years ago, Gilmore explained, Fisher had suffered a serious head injury from a gun-related accident and had never fully recovered his wits. The poor man was prone to spells of amnesia, blackouts, and derangement. It was very possible that Fisher had just wandered off.

Dr. Gilmore then calmly told the court that he had proof to back up his theory, and proceeded to drop a bombshell: Archibald Fisher was alive and staying in his home.

The courtroom murmured in shock.

Dr. Gilmore continued. Fisher had suffered from a terrible bout of memory loss and had no recollection of his time in Springfield. In fact, Fisher had wandered all the way to Peoria before regaining his senses. The only reason the man had failed to show up to the courtroom today was because his health prevented it.

Lincoln scanned the crowd with glee. “When the doctor’s story was first made public, it was amusing to scan and contemplate the countenances and hear the remarks of those who had been actively engaged in the search for the dead body,” he would later write in a letter, “some looked quizzical, some melancholy, and some furiously angry.”

At first, many were skeptical of the doctor’s claims, but officials were quick to confirm that Fisher was indeed alive. He’d eventually show up to court, later explaining how, indeed, he had no memory of ever visiting Springfield.

To the prosecution's great embarrassment, much of the evidence was proven bunk: It was soon discovered that the controversial path in the forest was, in fact, created by children who had been building a rope swing; meanwhile, the hairs in the woods belonged to a cow. It also became awfully clear that Henry Trailor had been coerced into making a false confession—when the officers had threatened Henry's life, Henry told them what they wanted to hear instead.

All of the charges would be dropped and the men's lives spared. “We have had the highest state of excitement here for a week past that our community has ever witnessed,” Lincoln would write after the trial.

In fact, the case enchanted Lincoln so much that he tried to immortalize the events in a short story written in the style of the true-crime genre. The future president, of course, was justifiably proud of the outcome: It wasn't every day that a single surprise witness helps solve a mystery and saves two people from the hangman's noose.

To read Lincoln's own account, check out this excerpt at Smithsonian.