More than 200 years have passed since physician James Parkinson first identified the degenerative neurological disorder that bears his name. Over five million people worldwide suffer from Parkinson’s disease, a neurological condition characterized by muscle tremors and other symptoms. Diagnosis is based on those symptoms rather than blood tests, brain imaging, or any other laboratory evidence.

Now, science may be close to a simple and non-invasive method for diagnosing the disease based on a waxy substance called sebum, which people secrete through their skin. And it’s thanks to a woman with the unique ability to sniff out differences in the sebum of those with Parkinson's—years before a diagnosis can be made.

The Guardian describes how researchers at the University of Manchester partnered with a nurse named Joy Milne, a "super smeller" who can detect a unique odor emanating from Parkinson's patients that is unnoticeable to most people. Working with Tilo Kunath, a neurobiologist at Edinburgh University, Milne and the researchers pinpointed the strongest odor coming from the patients' upper backs, where sebum-emitting pores are concentrated.

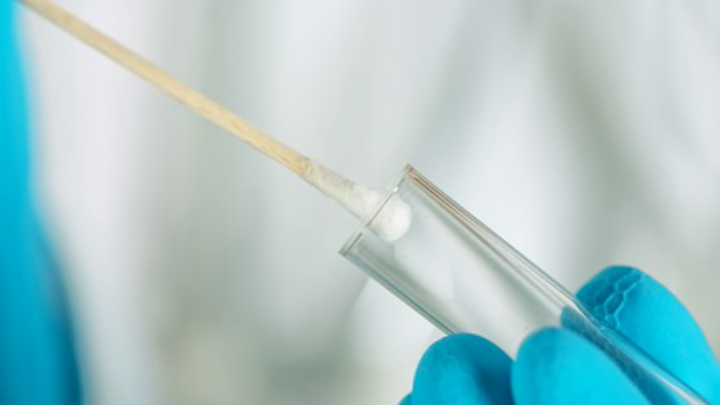

For a new study in the journal ACS Central Science, the researchers analyzed skin swabs from 64 Parkinson's and non-Parkinson's subjects and found that three substances—eicosane, hippuric acid, and octadecanal—were present in higher concentrations in the Parkinson’s patients. One substance, perillic aldehyde, was lower. Milne confirmed that these swabs bore the distinct, musky odor associated with Parkinson’s patients.

Researchers also found no difference between patients who took drugs to control symptoms and those who did not, meaning that drug metabolites had no influence on the odor or compounds.

The next step will be to swab a a much larger cohort of Parkinson’s patients and healthy volunteers to see if the results are consistent and reliable. If these compounds are able to accurately identify Parkinson’s, researchers are optimistic that it could lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective interventions.

[h/t The Guardian]