Photograph by Flickr user Adam Greig.

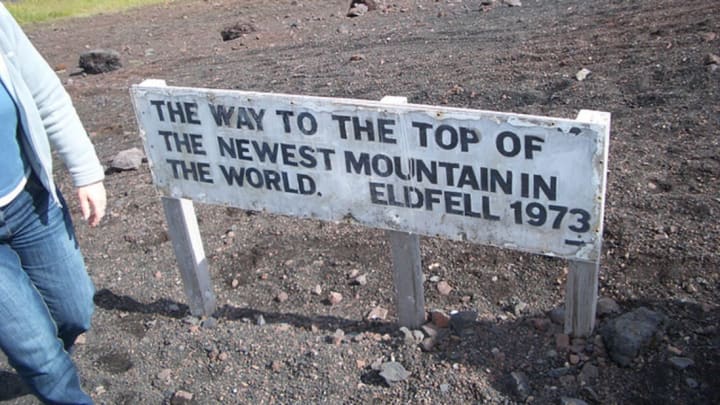

Eldfell is Icelandic for “mountain of fire.” The volcano named Eldfell came into being suddenly on January 23, 1973. It was a sight to see, but dangerous to be around. The people of Heimaey didn’t abandon their island home to the volcano, however. They made it work for them.

Photograph by Bruce McAdam.

Heimaey is a 13.4 square kilometer island just off the southern coast of Iceland. The name means “home island.” It is the largest and only populated island of the volcanic archipelago named Vestmannaeyjar, or “Westman Islands.” The newest island, Surtsey, is the product of a volcanic eruption in 1963. At the beginning of 1973, Heimaey was home to around 5,300 people, mostly clustered in the town of Vestmannaeyjar near Heimaey Harbor, at the north end of the island.

Seismographs on the Icelandic mainland picked up small tremors underneath Heimaey on January 21 and 22, but they were small and unnoticed by the residents. Then at 1:55 AM on the 23rd, the island opened up. A fissure opened up barely east of town and grew to two kilometers long, cracking the island from coast to coast. Lava spewed upward as far as three kilometers.

Photograph by Svienn Eirikksen, Vestmannaeyjar fire chief, via the U.S. Geological Survey.

Due to recent bad weather, almost the entire fishing fleet of Heimaey was in port and able to help with evacuating the island’s citizens. They were summoned by fire engine sirens to the port. The Icelandic State Civil Defence Organisation swung into action, sending boats over the four nautical miles from the mainland to evacuate people. By daybreak, most of the people were off the island. Hospital patients and the elderly were taken off by plane, and the evacuation was complete by the end of the day.

But the eruption continued. The line of lava fountains settled down to just two in a couple of days, and by February 6 only one remained, which built itself up into Eldfall volcano. In addition to lava, the volcano spewed huge amounts of tephra, which is ash, cinders, and rocks. Millions of tons of tephra rained down on Heimaey, setting some buildings on fire and burying others. About 400 buildings and homes were destroyed, a third of the island’s structures.

The lava flowed for five months, until July 3. Pretty soon after the evacuation, townspeople noticed that the huge lava flow was headed in the direction of the harbor. Heimaey Harbor was known as the best harbor in Iceland, a hub for fisherman and the backbone of commerce on the island. Iceland took on a huge and risky project to stop the lava and save the harbor. Vestmannaeyjar firemen sprayed water on the advancing lava with firehoses. The Fire Chief of the Keflavík International Airport, the University of Iceland, and various groups came together to devise a plan to bring more water to the lava. Pumps were brought in from Iceland and other nations, The dredging boat Sandey was brought in on March first, and not only sprayed the lava, but brought pipes to lay across the crust of the lava to take water where it was needed.

Where the lava stopped. Photograph by Richard S. Williams, Jr., U.S. Geological Survey.

By March 26, additional pumping equipment was shipped in from the United States. Three months of pumping huge amounts of seawater onto the lava finally stopped its progress toward the harbor. By the time pumping stopped in the middle of May, the pumps had begun to wear out. It is estimated that 6.2 million metric tonnes of seawater had been sprayed on the lava of Eldfell, which left 220 thousand metric tonnes of salt. The lava cooling project was wound down in June of 1973. The harbor was saved.

Graphic by Islander.

By the time the river of lava stopped, it had added another 20% to the area of Heimaey Island. The extra basalt around the edges of the harbor actually improved it, by providing a wall of shelter against the rough sea. Around 4,000 of the island’s inhabitants returned to rebuild and resume their lives on Heimaey.

Photograph by Flickr user globetrotter_rodrigo.

The lava-cooling project led directly to another project that perfectly illustrates making lemonade out of lemons. In 1983, a new 5 megawatt heat-exchanger plant was opened on Heimaey to heat the homes of Vestmannaeyjar. It had been planned since 1974, with the design approved in 1979. The plant takes heat from the still-warm lava by spraying water on it and collecting the steam that rises as a result. The steam heats a water-circulating system that is connected to the town. It was the world’s first geothermal system to take advantage of the heat from lava.

Eldfell is the brown hill on the right. Helgafell, an older volcano, is the hill on the left. The original fissure is in black, and the town of Vestmannaeyjar is in the background. Photograph by Wirthi.

In 2006, excavations began to unearth the homes of Heimaey that had been buried in ash for 30 years. At least one of the excavated homes is the centerpiece of Eldheimar, a museum dedicated to the 1973 eruption, set up in Vestmannaeyjar near Eldfell.

In case you have heard of Heimaey, but didn’t know about the volcano, it may have been because it was the home of Keiko the killer whale, the star of the movie Free Willy, who was taken there in 1998 after living in Oregon for two years.

This article was inspired by a post at Metafilter.