When scientists use these words, they typically mean something completely different than what they do when non-scientists use them. Our definitions may be too narrow or too broad, or we use terms interchangeably when they actually shouldn't be. Let’s set the record straight.

- Poisonous and Venomous

- Microbe

- Meteor, Meteorite, and Asteroid

- Theory

- Fossil

- Common Ancestor

- Hominin

- Dinosaur

- Pterosaur

- De-extinction

Poisonous and Venomous

The words poison and venom both describe a toxin that interferes with a physiological process, and they are often used interchangeably—but there is a difference. It’s all about how the substance is delivered: Venom is delivered via an anatomical device like fangs, while poison is usually inhaled, ingested, or absorbed. For example, the rough-skinned newt and the blue-ringed octopus both produce a powerful toxin called tetrodotoxin. But scientists call the octopus “venomous” because it delivers the substance through a bite, and consider the newt “poisonous” because the toxin is in its skin.

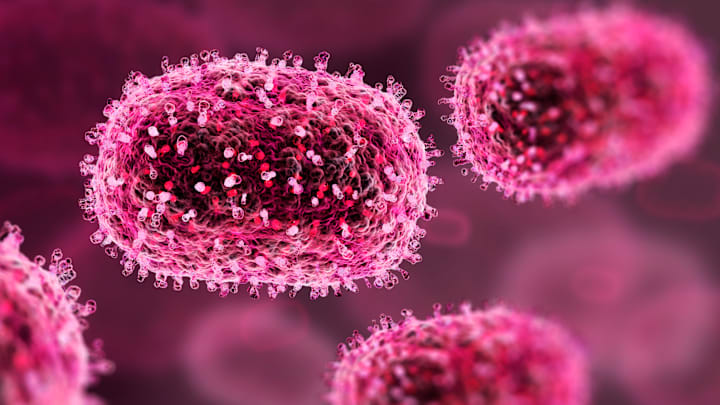

Microbe

When most people hear the word microbe, they think of stuff that they can’t see that’s going to make them sick. But while some microbes do cause disease, not all microbes (a.k.a. microscopic organisms) are bad. In fact, some are essential for life. Microbes include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa, and make up most of the life on our planet. For every human cell in our bodies, there are about 10 resident microbes; only a small percentage are pathogens.

Meteor, Meteorite, and Asteroid

Meteors, meteorites, and asteroids are all different things. Here’s how to use the terms correctly:

- Asteroids are the rocky bodies that orbit the sun and are mostly located between Mars and Jupiter. They’re much smaller than planets, and they’re sometimes pulled out of their orbit by the force of Jupiter’s gravity and travel toward the inner solar system.

- Meteorites are rocks that fall to Earth from space and actually reach Earth’s surface. The vast majority were once parts of asteroids.

- Meteors are also objects that enter Earth’s atmosphere from space, but they’re typically grain-sized pieces of comet dust that burn up before reaching the ground, leaving behind trails (called shooting stars) as they vaporize.

Theory

When most people use the word theory, they’re talking about a hunch or guess. But for scientists, a theory is a well-substantiated, and testable, explanation that incorporates laws, hypotheses, and facts. The theories of gravity and evolution, for example, aren’t mere hunches; they explain why apples fall from trees and how so many very different plants and animals exist, and have existed, on Earth. “A theory not only explains known facts; it also allows scientists to make predictions of what they should observe if a theory is true,” the American Museum of Natural History writes on its website. Scientific theories are also testable; if evidence isn’t compatible with a theory, scientists can either go back to refine the theory, or reject it altogether.

Fossil

Fossils aren’t just the remains of hard parts of animals like bones, teeth, and shells. Under the right conditions, organisms’ soft parts—like skin impressions and outlines—can also fossilize. Other things that qualify as fossils are traces made by organisms, like footprints, burrows, and nests. Fun fact: By most definitions, in order to qualify as a fossil, the specimen must be more than 10,000 years old. If it’s younger than that, the specimen is a subfossil.

Common Ancestor

When you use the term common ancestor, you might mean that one creature evolved from another. But that oversimplifies it: Humans didn’t evolve from monkeys, for example, but share a common ancestor with apes. Genetic analysis of fossils suggests that humans and chimpanzees share a common ancestor who lived millions of years ago, and the evolutionary group containing humans and chimps split from those of the other great apes at least 5 million years ago. Plus, research shows that all species on Earth are descended from a common ancestor, even if the exact identity of the ancestor is not known.

You May Also Like:

- 11 Naughty-Sounding Scientific Names (and What They Really Mean)

- 25 Smart Words You Should Be Using But Aren’t

- The Science Behind Why People Hate the Word ‘Moist’

Hominin

If you’re using the term hominids to refer to humans and their ancestors, your scientific vocabulary needs an update. The definition of that word has expanded to refer to all extant great apes—humans, gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, and bonobos—and their ancestors. To describe the group comprised of modern humans, extinct human species, and our immediate ancestors, you should be using the word hominins.

The first hominin fossil, the skull of a Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) was discovered in 1848 in Gibraltar, and since then, many hominin fossils, comprising many different species, have been discovered. These species emerged in different places over the past six or seven million years, and some of them even lived simultaneously.

Dinosaur

We typically say that all dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, but that’s not actually the case. In fact, if you look out your window, you might see one right now. Birds descended from the common ancestor of all dinosaurs, making them a modern kind of dinosaur. So go ahead: Tell your friends that pigeon is a dinosaur. They'll never look at those birds the same way again.

Pterosaur

Chances are, you probably haven't been using this word much at all. That's because most of us grew up thinking that pterosaurs like the pterodactyl were dinosaurs, and that's what we called them. But these animals weren’t dinosaurs, and they weren’t birds, either. They were actually flying reptiles, cousins to the dinosaurs that evolved on a separate branch of the reptile family tree. Pterosaurs were the first animals after insects to evolve powered flight by flapping their wings to generate lift.

De-extinction

You probably understand what de-extinction is, but you might not understand what kinds of animals we may be able to bring back—and you have Hollywood to thank for that. Despite what you saw in Jurassic Park, scientists will never be able to resurrect non-avian dinosaurs from extinction; any DNA that might be found is just too old to be used. But for other species, science might find a way in the not-too-distant future. In 2003, researchers implanted a goat egg with genes from an extinct Spanish mountain goat and used a goat-ibex as a surrogate; the resulting animal lived for just a few minutes, but the experiment proved it could be done. More recently, geneticists extracted genes from dire wolf fossils and engineered them into a gray wolf genome, resulting in three gray wolf puppies with some dire wolf DNA.

A version of this article was published in 2015; it has been updated for 2025.