When Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released by Walt Disney in 1937, it was accompanied by a cascade of licensed merchandise. Tea sets, a wind-up Dopey toy, a sand pail, and a board game were among the items on offer. Both the movie and its ancillary products were a tremendous success, though it would be decades before movie studios made a habit of licensing their characters for consumer goods. It wasn't until Fox’s 1977 release of Star Wars that entertainment properties were considered to be highly marketable on store shelves. Today, creative property owners can make as much, if not more, on tie-in products as they do on the movies, television shows, or books that inspired them.

To trace the source of that strategy, you have to go back further than Star Wars and decades prior to Snow White. According to Smithsonian, it was Peter Rabbit creator Beatrix Potter who emerged as the unlikely pioneer of character licensing. She was virtually a one-woman operation, designing prototype products and vetting the quality of licensed goods some 30 years before Dopey ever took his first spring-assisted step.

Born Helen Beatrix Potter on July 28, 1866, the author spent her formative years under the care of a governess and largely left to her own imagination on the third floor of her wealthy family’s home in London’s posh Bolton Gardens area. Potter rarely ventured outdoors until a family vacation took them to a summer getaway, where she soaked up animals, insects, and plant life, even taking several animals home with her for a domestic menagerie. The collection included two rabbits, which she named Peter and Benjamin Bouncer. That fascination with furry things eventually led her to detail the adventures of Peter Rabbit in a letter to her former governess’s son, Noel, in 1893. Noel and his siblings were delighted by Peter, who was presented as a mischievous young rabbit living in a sandbank.

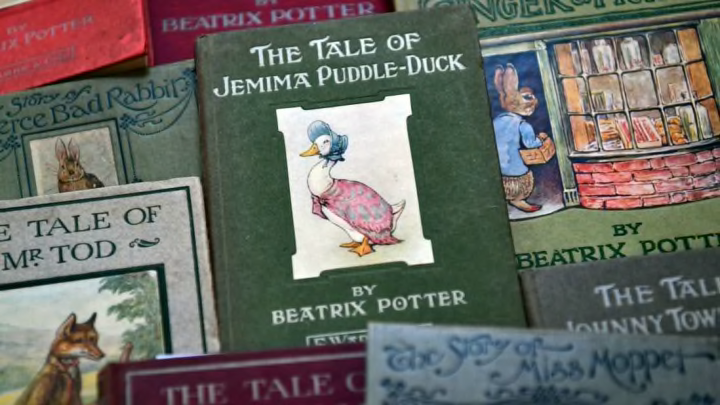

Later, Potter decided to produce a book of Peter Rabbit’s adventures, using the letter as source material and filling it out with illustrations. Though she initially had trouble finding a publisher and had to print off 450 copies to sell at her own expense, The Tale of Peter Rabbit was eventually published by Frederick Warne and Company in 1902 to great acclaim, moving 28,000 copies that first year. Potter would go on to write 22 more books, including 1903’s The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and 1913’s The Tale of Pigling Bland. Her cast of characters grew to include Jemima Puddle-Duck, Samuel Whiskers, and Tom Kitten.

From the beginning, Potter was fascinated with the idea of taking her creations from the pages of her palm-sized books and into other mediums. She wasn't the first (author John Newberry packaged his books with toys in 1744), but Potter would be the most organized. Inspired by London department store Harrods' marketing products based on an advertising character named Sunny Jim, Potter decided to begin sewing a stuffed Peter Rabbit doll herself, hoping to get the character’s proportions and look right before finding a production partner. Patenting the doll in December 1903—a highly unusual and savvy move—Potter wrote to one of her publishers, Norman Warne, with a progress report:

“I am cutting out calico patterns of Peter, I have not got it right yet, but the expression is going to be lovely … I think I could make him stand on his legs if he had some lead bullets in his feet!”

The doll was eventually produced sans ammunition and became a hit. For years, Potter became preoccupied with merchandising, designing a board game, painting figurines, and carefully overseeing licensed Potter paraphernalia from tea sets to puzzles to bookcases made especially for her books. With each licensee, Potter was careful to make sure the contractual language was to her benefit. Though she liked the Warnes, they had erred in failing to copyright The Tale of Peter Rabbit in America, leading to knock-offs. Writing of an agreement to produce a china set with her characters, Potter told Harold Warne:

“I have been thinking about that china agreement, it is rather an awkwardly worded document. I think the words ‘all earthenware’ would prevent me from offering the statuettes to other firms …But if you decide to let them go on making tea-sets—with a promise of improvement—I should think the agreement had better be written out again? In a less wholesale style? The agreement with Hughes seems a much better model.”

Although the Warnes worked with Potter on licensing, it was Potter who often took the lead. Between 1907 and 1917, she was heavily involved in products ranging from slippers to stationery. When World War I broke out and production slowed, Potter took the opportunity to break off from companies she had become dissatisfied with. Among the casualties: Hughes, which made soft rabbit toys, and Levien, which made the tea set that seemed to disappoint her.

When she agreed to let manufacturer J.K. Farnell make a Jemima Puddle-Duck doll in 1910, she personally visited their factory to collect her royalty payments. When another company planned on making fabric characters in 1923, Potter declared them awful and forced them to revise their plans until they were to her satisfaction. The fabric items came out three years later, in 1926.

If someone had a better idea, Potter was willing to listen. After designing the board game in 1904, she set it off to the side. In 1917, Fruing Warne’s wife, Mary, suggested some tweaks that made it more kid-friendly. Potter tested both on her nieces and determined Mary’s version was better. Peter Rabbit’s Race Game was released in 1919. Potter funneled the profits directly to Mary.

Potter did involve Norman Warne in another capacity. She became engaged to him in 1905, though he tragically died of pernicious anemia just weeks following the announcement. Potter eventually married in 1913, at age 47, to William Heelis, a real estate solicitor who had helped her locate to a residence in Cumbria. When Heelis also died early, Potter was without a spouse and without heirs. Upon her death on December 22, 1943, her will left her characters and the rights to their merchandising fortunes to the Warnes, who continued to market them through the 20th century and beyond. By 1981, Beatrix Potter ephemera was taking in $5 million annually, including Peter Rabbit-adorned wallpaper and serving trays.

Today, Peter Rabbit merchandise is marketed through Penguin Random House, a cotton-tailed empire with an estimated value of $500 million. The images and characters remain popular in a climate where licensed characters are commonplace and revenue for official merchandising of all kinds of products from Marvel heroes to Disney icons is a $270 billion annual business. That can be traced back to Potter, who spent several hours stitching her own Peter Rabbit in the knowledge that readers would one day want to fill their shelves with more than just books.