Abolitionist John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry on October 16, 1859, was meant to start an armed slave revolt, and ultimately end slavery. Though Brown succeeded in taking over the federal armory, the revolt never came to pass—and Brown paid for the escapade with his life.

In the more than 160 years since that raid, John Brown has been called a hero, a madman, a martyr, and a terrorist. Now Showtime is exploring his legacy with an adaption of James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird. Like the novel it’s based on, the miniseries—which stars Ethan Hawke—will cover the exploits of Brown and his allies. Here's what you should know about John Brown before you watch.

1. John Brown was born into an abolitionist family on May 9, 1800.

John Brown was born to Owen and Ruth Mills Brown in Torrington, Connecticut, on May 9, 1800. After his family relocated to Hudson, Ohio (where John was raised), their new home would become an Underground Railroad station. Owen would go on to co-found the Western Reserve Anti-Slavery Society and was a trustee at the Oberlin Collegiate Institute, one of the first American colleges to admit black (and female) students.

2. John Brown declared bankruptcy at age 42.

At 16, Brown went to school with the hope of becoming a minister, but eventually left the school and, like his father, became a tanner. He also dabbled in surveying, canal-building, and the wool trade. In 1835, he bought land in northeastern Ohio. Thanks partly the financial panic of 1837, Brown couldn’t satisfy his creditors and had to declare bankruptcy in 1842. He later tried peddling American wool abroad in Europe, where he was forced to sell it at severely reduced prices. This opened the door for multiple lawsuits when Brown returned to America.

3. John Brown's Pennsylvania home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Sometime around 1825, Brown moved himself and his family to Guys Mills, Pennsylvania, where he set up a tannery and built a house and a barn with a hidden room that was used by slaves on the run. Brown reportedly helped 2500 slaves during his time in Pennsylvania; the building was destroyed in 1907 [PDF], but the site, which is now a museum that is open to the public, is on the National Register of Historic Places. Brown moved his family back to Ohio in 1836.

4. After Elijah Lovejoy's murder, John Brown pledged to end slavery.

Elijah Lovejoy was a journalist and the editor of the St. Louis/Alton Observer, a staunchly anti-slavery newspaper. His editorials enraged those who defended slavery, and in 1837, Lovejoy was killed when a mob attacked the newspaper’s headquarters.

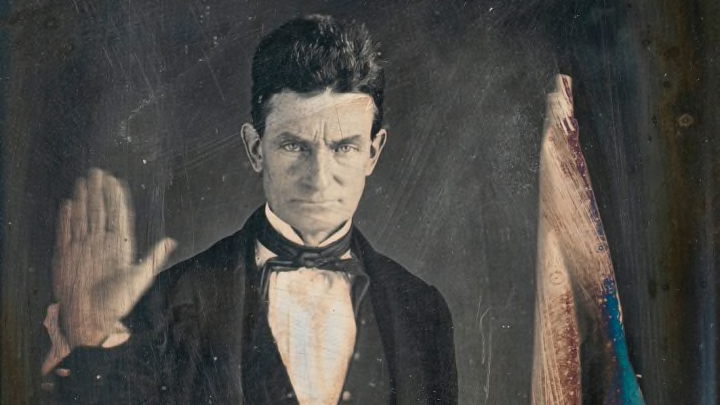

The incident lit a fire under Brown. When he was told about Lovejoy’s murder at an abolitionist prayer meeting in Hudson, Brown—a deeply religious man—stood up and raised his right hand, saying “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery."

5. John Brown moved to the Kansas Territory after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which decreed that it would be the people of Kansas and Nebraska who would decide if their territories would be free states or slave states. New England abolitionists hoping to convert the Kansas Territory into a Free State moved there in droves and founded the city of Lawrence. By the end of 1855, John Brown had also relocated to Kansas, along with six of his sons and his son-in-law. Opposing the newcomers were slavery supporters who had also arrived in large numbers.

6. John Brown’s supporters killed five pro-slavery men at the 1856 Pottawatomie Massacre.

On May 21, 1856, Lawrence was sacked by pro-slavery forces. The next day, Charles Sumner, an anti-slavery Senator from Massachusetts, was beaten with a cane by Representative Preston Brooks on the Senate floor until he lost consciousness. (A few days earlier, Sumner had insulted Democratic senators Stephen Douglas and Andrew Butler in his "Crime Against Kansas" speech; Brooks was a representative from Butler’s state of South Carolina.)

In response to those events, Brown led a group of abolitionists into a pro-slavery settlement by the Pottawatomie Creek on the night of May 24. On Brown’s orders, five slavery sympathizers were forced out of their houses and killed with broadswords.

Newspapers across the country denounced the attack—and John Brown in particular. But that didn't dissuade him: Before his final departure from Kansas in 1859, Brown participated in many other battles across the region. He lost a son, Frederick Brown, in the fighting.

7. John Brown led a party of liberated slaves all the way from Missouri to Michigan.

In December 1858, John Brown crossed the Kansas border and entered the slave state of Missouri. Once there, he and his allies freed 11 slaves and led them all the way to Detroit, Michigan, covering a distance of more than 1000 miles. (One of the liberated women gave birth en route.) Brown’s men had killed a slaveholder during their Missouri raid, so President James Buchanan put a $250 bounty on the famed abolitionist. That didn’t stop Brown, who got to watch the people he’d helped free board a ferry and slip away into Canada.

8. John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry was meant to instigate a nationwide slave uprising.

On October 16, 1859, Brown and 18 men—including five African Americans—seized control of a U.S. armory in the Jefferson County, Virginia (today part of West Virginia) town of Harpers Ferry. The facility had around 100,000 weapons stockpiled there by the late 1850s. Brown hoped his actions would inspire a large-scale slave rebellion, with enslaved peoples rushing to collect free guns, but the insurrection never came.

9. Robert E. Lee played a part in John Brown’s arrest.

Shortly after Brown took Harpers Ferry, the area was surrounded by local militias. On the orders of President Buchanan, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee entered the fray with a detachment of U.S. Marines. The combined might of regional and federal forces proved too much for Brown, who was captured in the Harpers Ferry engine house on October 18, 1859. Ten of Brown's men died, including two more of his sons.

10. John Brown was put on trial a week after his capture.

After his capture, Brown—along with Aaron Stevens, Edwin Coppoc, Shields Green, and John Copeland—was put on trial. When asked if the defendants had counsel, Brown responded:

"Virginians, I did not ask for any quarter at the time I was taken. I did not ask to have my life spared. The Governor of the State of Virginia tendered me his assurance that I should have a fair trial: but, under no circumstances whatever will I be able to have a fair trial. If you seek my blood, you can have it at any moment, without this mockery of a trial. I have had no counsel: I have not been able to advise with anyone ... I am ready for my fate. I do not ask a trial. I beg for no mockery of a trial—no insult—nothing but that which conscience gives, or cowardice would drive you to practice. I ask again to be excused from the mockery of a trial."

Brown would go on to plead not guilty. Just days later, he was found “guilty of treason, and conspiring and advising with slaves and others to rebel, and murder in the first degree” and was sentenced to hang.

11. John Brown made a grim prophecy on the morning of his death.

On the morning of December 2, 1859, Brown passed his jailor a note that read, “I … am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with blood.” He was hanged later that day.

12. Victor Hugo defended John Brown.

Victor Hugo—the author of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, who was also an abolitionist—penned an open letter on John Brown’s behalf in 1859. Desperate to see him pardoned, Hugo wrote, “I fall on my knees, weeping before the great starry banner of the New World … I implore the illustrious American Republic, sister of the French Republic, to see to the safety of the universal moral law, to save John Brown.” Hugo’s appeals were of no use. The letter was dated December 2—the day Brown was hanged.

13. Abraham Lincoln commented on John Brown's death.

Abraham Lincoln, who was then in Kansas, said, “Old John Brown has been executed for treason against a State. We cannot object, even though he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong. That cannot excuse violence, bloodshed and treason. It could avail him nothing that he might think himself right.”

14. John Brown was buried in North Elba, New York.

In 1849, Brown had purchased 244 acres of property from Gerrit Smith, a wealthy abolitionist, in North Elba, New York. The property was near Timbuctoo, a 120,000-acre settlement that Smith had started in 1846 to give African American families the property they needed in order to vote (at that time, state law required black residents to own $250 worth of property to cast a vote). Brown had promised Smith that he would assist his new neighbors in cultivating the mountainous terrain.

When Brown was executed, his family interred the body at their North Elba farm—which is now a New York State Historic Site.

15. The tribute song "John Brown's Body" shares its melody with “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

It didn’t take long for Brown to become a martyr. Early in the 1860s, the basic melody of “Say Brothers Will You Meet Us,” a popular camp hymn, was fitted with new lyrics about the slain abolitionist. Titled “John Brown’s Body,” the song spread like wildfire in the north—despite having some lines that were deemed unsavory. Julia Ward Howe took the melody and gave it yet another set of lyrics. Thus was born “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a Union marching anthem that's still widely known today.