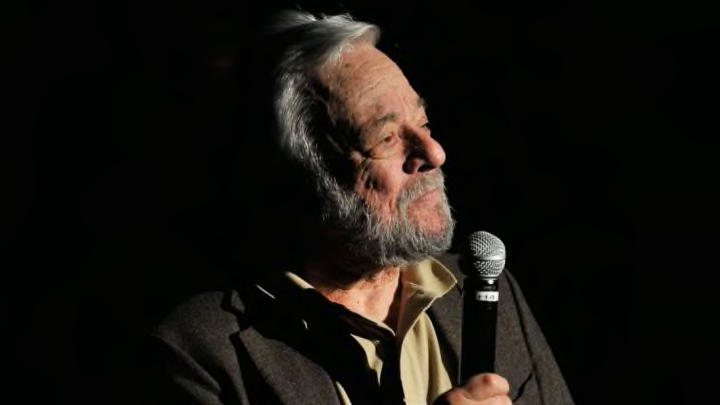

Composer, lyricist, and Broadway legend Stephen Sondheim passed away on November 26, 2021 at the age of 91. Celebrate his life with a look back at a few of the many iconic songs he wrote over the course of his career.

1. “Maria” // West Side Story (1957)

Though Sondheim enjoyed composing music much more than writing lyrics, he came on board Arthur Laurents’ Romeo and Juliet update to write lyrics for music composed by Leonard Bernstein. The song “Maria” happens when Maria and Tony— sister of the leader of a Puerto Rican gang called the Sharks and a former member of a rival gang called the Jets, respectively—meet at a school dance. There, they exchange a few words, dance, and fall in love.

“The problem here,” Sondheim wrote in Finishing the Hat, “was how to write a love song for two people who have just met. They have exchanged exactly 10 lines, but they have encountered each other in a surreal, dreamlike dance sequence, so that the audience believes that they have an intimate, even mystical, connection. Nevertheless, when the gymnasium set dissolves into the street outside Maria’s house and Tony is back in reality, he has to sing something real.” The only things Tony knows about Maria at this point are her name, and that she’s Puerto Rican—so, said Sondheim, the only thing he could think to make him sing rapturously about was her name.

There was another reason for “Maria,” too: Originally, Tony had been “a blond Polish Catholic, in order to contrast him as much as possible with the Puerto Ricans,” Sondheim wrote. “This gave the name ‘Maria’ a religious resonance, which I pushed with the line ‘Say it soft and it’s almost like praying.’” The Polish-Catholic thing was eventually dropped, though, and Sondheim laments that now, the line “makes little sense and merely contributed a kind of overall wetness to the lyric—a wetness, I regret to say, which persists throughout all the romantic lyrics in the show, but which appealed to my collaborators and which may very well have contributed to the score’s popularity.”

2. “Rose’s Turn” // Gypsy (1959)

Though he was worried that writing lyrics would pigeonhole him as a lyricist, Sondheim picked up his pen again to write the lyrics for the Ethel Merman vehicle Gypsy, with a book by Laurents and music by Jule Styne. Sondheim called the musical, which was loosely based on the memoirs of famous burlesque entertainer Gypsy Rose Lee (aka Louise) and focusing on her domineering stage mother, Rose, “the show where I came of age—lyrically, at any rate.”

Originally, the scene featuring Rose’s breakdown wasn’t going to be a song at all, but “a surreal ballet, in which Rose would be confronted by all the people in her life,” according to Sondheim. But a week into the rehearsals, choreographer Jerome Robbins said he wouldn’t have time to teach Merman a ballet. So it would have to be a song. Styne had a prior engagement that night, so Sondheim sat down with Robbins to discuss what the number should be: “I suggested to Jerry that since he wanted all the people in the story to collide in a ballet, perhaps if Rose’s breakdown were to be sung rather than danced it could comprise fragments of all the songs associated with her and the people in her life; the songs we’d heard all evening, colliding in an extended surreal medley consisting of fragments of the score.” As Sondheim improvised on the piano, Robbins danced across the stage, “like a stripper, but a clumsy one: like Rose doing a strip,” Sondheim wrote. “That was the beginning of three exhilarating hours of musical and choreographic improvisation, as we shaped and constructed the number to be a summary of the score. I even improvised lyrics, something which was anathema to me.”

The next day, Sondheim and Styne filled out the number, then played it for Merman at rehearsal. She was unsure: “It’s sorta more an aria than a song,” she said, but Sondheim was able to assure her that “it was merely a collage of songs that she had either sung or heard during the course of the show. That seemed to calm her.”

During previews, “Rose’s Turn” ended on a much different note. “I had persuaded Jule to end the number on a high, dissonant chord of eerie violin harmonics: a woman having a nervous breakdown would not wind up on a triumphant tonic chord,” Sondheim wrote. But when his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein II, came to see the show, he suggested that the song end in a show-stopping climax. Otherwise, he argued, the audience would be waiting for the curtain call, when they could give Merman the ovation she deserved, instead of listening to the scene that followed the song, in which Rose and Louise reconciled and made the point that all children become their parents. “Gently chastened, I gave up and we affixed a big ending and a tonic chord to the song,” Sondheim wrote. “Ethel got an enormous ovation and the audience listened to the last scene in rapt silence. Lesson learned.”

3. “Ladies Who Lunch” // Company (1970)

Company’s Joanne—a cynical older woman who is friends with the show’s main character, Robert—was based on the legendary Elaine Stritch, “or at least on her acerbic delivery of self-assessment,” Sondheim wrote in Finishing the Hat.

The song “Ladies Who Lunch” marked the third time (after Gypsy and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) that the lyricist/composer had to write music and lyrics for a specific personality playing a character: “The song fit her perfectly, the only problem occurring when, in all innocence, she asked me what kind of pastry ‘a piece of Mahler’s’ referred to.” Stritch would later recount how she thought Mahler’s was “a pastry shop on Broadway ... The ladies had lunch, they went to see a matinee, they saw a Pinter play, and then afterwards, they went around the corner and had a cup of tea and a piece of Mahler’s. Made perfect sense to me. When I brought it up to Stephen Sondheim, he said, ‘Elaine, I have to go to the bathroom.’” (Gustav Mahler was a Jewish composer.)

Sondheim had hoped that the number would be a showstopper, and the audience would actually stand up when Stritch said “Rise!” over and over and give the performer a standing ovation. “It was a showstopper, but not quite that big,” he wrote. “My hope was probably a holdover from my Hollywood fantasies in which one opening night's black-tied men and bejeweled women stood up at anything—much as they do nowadays, where standing ovations are a forgone conclusion, it being necessary for audiences to remind themselves that they’ve had a live experience by participating in it.”

4. “Send In The Clowns” // A Little Night Music (1973)

A Little Night Music, with lyrics and music by Sondheim, was based on Ingmar Bergman’s 1955 film Smiles of a Summer Night. The song that appeared in this second act scene was supposed to belong to the male lead, Fredrick, a middle-aged lawyer in an unconsummated marriage with a much younger woman. He is tempted to reignite an affair with Desiree, an older actress, “since the action is his, the passive reaction being Desiree’s, and I started to write one,” Sondheim wrote. But Desiree had only two songs in the first act, neither a solo, so director Hal Prince suggested that the scene might be the ideal place to give Desiree a solo, and that “he had directed it so that the thrust of the action came from her rather than from Fredrik. I went skeptically to see a rehearsal, and he had indeed accomplished what he had promised.”

Desiree was played by Glynis Johns, whose voice, Sondheim wrote, was “small but silvery, musically and smokily pure,” and whose biggest limitation was her inability to hold a note. “The solution was to write short breathy phrases for her, which suggested to me that they should be questions rather than statements,” Sondheim wrote. “Once I’d reached that conclusion, the song wrote effortlessly … The song sat so well in Glynis’s voice that at the recording session, even though she’d been in a recording studio only once before (for the Disney movie of Mary Poppins), she did it perfectly in one take.”

“Send in the Clowns” was a huge hit for the composer/lyricist. “Why so many fine (and not so fine) singers have recorded ‘Send in the Clowns’ is a mystery to me,” he wrote. “For two years after A Little Night Music opened, the only even faintly known vocalist who took an interest in it was Bobby Short, a singer and piano player who performed it in nightclubs, where it made no impression on even that tiny and dwindling audience. Then Judy Collins recorded it in England, where it incomprehensibly became a hit, after which Frank Sinatra’s recording made it an even bigger one, and soon enough virtually everybody in the pop field climbed on the bandwagon. … It even won a Grammy Award as Song of the Year in 1975, amid rock and pop contenders—a song from a musical, no less. (It’s the last one that did.)”

5. “On The Steps Of The Palace” // Into The Woods (1986)

After his first collaboration with book-writer James Lapine, Sunday in the Park with George, Sondheim suggested that they “write a quest musical along the lines of The Wizard of Oz, the one movie musical I loved in which the songs not only defined the characters and carried the story forward but were wonderful stand-alone songs as well.” Lapine combined all of the classic Grimm fairy tale characters and added a Baker and his Wife, who are unable to conceive, thanks to a curse put on his family by a Witch.

The story, of course, included Cinderella. “The story of Cinderella has always struck me as the most incomprehensible of all the moral fables known as fairy tales,” Sondheim wrote in Look, I Made a Hat. “Here is a plain, depressed slave of a girl, beaten and maltreated by her [stepfamily who] … suddenly finds herself magically transformed into a radiant, opulently dressed beauty, sought after by the Prince of the Kingdom, who three times flees the palace where she is the belle of the ball to return to the hole in a corner of the house where she is a virtual prisoner. And she can’t decide which place to choose?”

Lapine came up with a twist that makes sense: The accident of leaving her slipper behind isn’t an accident at all; Cinderella chooses to leave it there. “She knows she’s an imposter and doesn’t want willingly to mislead the Prince (and the world),” Sondheim wrote. “She figures that if the Prince really cares to see her again, he’ll follow the clue she has left.” Cinderella’s big song in Into the Woods, “On the Steps of the Palace,” shows the future princess coming to the decision to leave her shoe behind. Wrote Sondheim, “No one, as far as I know, has ever made this observation, and if there were no other reason to write this book, the opportunity for me to point out James’s insight would be justification enough.”

6. “How I Saved Roosevelt” // Assassins (1990)

This musical—with a book by John Weidman, and based on an idea by Charles Gilbert, Jr.—featured all of the 13 people who have tried (or succeeded) to kill American Presidents. “How I Saved Roosevelt” is about a 1933 assassination attempt on Franklin D. Roosevelt, which occurred in Miami; instead of hitting the President-elect, unemployed brick layer Giuseppe Zangara, who fired six rounds, hit Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who later died from his wounds.

Sondheim painstakingly researched to write the song. “There were in fact five bystanders who claimed to take the actions described in the song, although no one deflected Zangara by pushing his arm in the air,” Sondheim wrote. “He had the misfortune to be only five feet tall and had arrived too late at the arena to get a seat close to the front. Roosevelt’s speech was unusually brief, and, as he started to sit down, Zangara was hastening to shoot when the entire audience rose to its feet in applause and blocked his view, forcing him to stand on his seat, which wobbled just enough to ruin his aim. Thus Roosevelt was indeed saved.”

There was also a song about the time Theodore Roosevelt was shot, but it was cut. “The bullet would have pierced Roosevelt’s heart were it not for the steel eyeglass case and the fifty-page speech lodged in the breast pocket of his jacket,” Sondheim wrote. “So one Roosevelt was saved by being long-winded and the other by being terse, a ripe opportunity for a song if I ever heard one.”

A version of this story ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2021.