Amid the busy streets and rugged landscape of Colorado Springs, Colorado, a number of strange huts stands out from the indie boutiques and red rocks. The structures look quaint and elfin—octagonal with pointy shingled roofs and small windows—and these days, they're used as storage sheds or art studios. Some have been converted into bus stops, and one is a café. But as quirky as they are, the huts are also curious relics of medical history: They once housed recovering tuberculosis patients.

A City Built on Disease

The history of Colorado Springs is tied firmly to tuberculosis. One of the deadliest diseases in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, tuberculosis is a bacterial condition that targets the lungs and causes a prolonged cough, along with fever and chills. It was called consumption due to patients' severe weight loss and physical deterioration—the disease seemed to literally consume them. There was no cure before antibiotics were developed in the 1940s. Because fresh, dry air was thought to dry out the moisture in patients' lungs and make breathing less labored, many sufferers sought treatment in high, arid climates like Colorado Springs.

The city was founded in 1871 by General William Jackson Palmer, a Civil War hero and railroad tycoon who had hopes of enticing residents with the region’s scenic beauty. Colorado Springs, nicknamed the City of Sunshine, was also marketed as a health resort due to its high altitude, mineral water springs, and abundant sunlight. Advertisements from the Colorado Springs Chamber of Commerce helped spread the word, claiming the air to be “100 percent aseptic” and free of the germs that might otherwise lurk in stuffy cities.

People seeking treatment for tuberculosis started arriving in Colorado Springs in the 1870s to rest and recover—or, unfortunately, die. In the 1890s, new tuberculosis sanatoriums brought tens of thousands of people to the region. Leah Davis Witherow, curator of history at the Colorado Springs Pioneer Museum, writes that “by 1900, approximately 20,000 health-seekers emigrated to the southwest each year,” with one-third of Colorado residents coming to the state “in search of a cure for themselves or a close family member” [PDF].

Many who recovered stayed and started a new life in Colorado Springs, so the town’s population boom is largely attributed to tuberculosis. “A lot of people would just show up in Colorado Springs hoping to get treatment or to recover on their own,” Matt Mayberry, director of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, tells Mental Floss. “Tuberculosis was our first major industry in Colorado Springs. We were really just a resort town but tuberculosis became the major driving force of our economy from about the 1880s until after World War II.”

Tiny Tents and Sun Baths

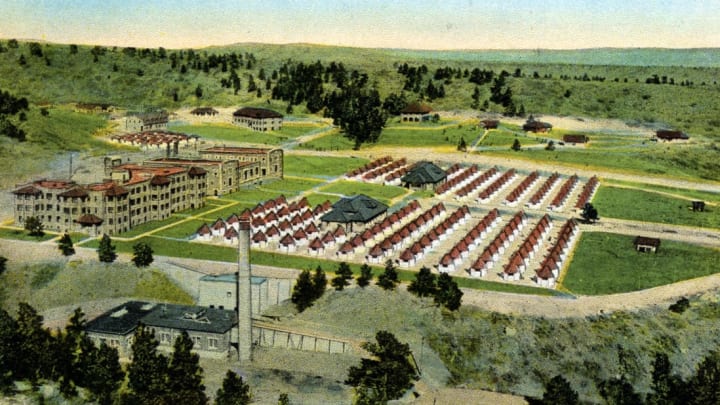

At the height of tuberculosis treatment efforts in 1917, over a dozen sanatoriums dotted the region, each accompanied by a number of TB huts. Major sanatoriums like the Modern Woodmen of America's, which treated members of the fraternal benefit society for free, had over 200 patients.

Each invalid lived in his or her own hut (officially called the Gardiner Sanitary Tent) designed by Charles Fox Gardiner and inspired by the teepee, which is built to boost airflow. Made of wood or canvas, the huts were open at the top and had several openings around the base for fresh air. Each hut was steam-heated and included a bed, closet, chairs, washstand, and electric lights.

“Tuberculosis huts were what we might think of today as tiny houses. They each hosted one patient. The purpose of the hut was to keep patients isolated and help them learn how to keep from spreading the disease,” Mayberry says.

Besides self-isolation, part of the open-air treatment required patients to sit outside in steamer chairs for six to eight hours a day—even during winter. Ventilation was seen as necessary for recovery, since it prevented germs from hanging in the air. Some facilities even prohibited talking during rest periods. The dry air was thought to help dry the moisture from the lungs. Heliotherapy was also popular; patients were instructed to lounge in the sun for extended periods of time. While there’s little evidence today that sunbathing did much to help sufferers, it was believed that prolonged sun exposure would help kill the bacteria that causes tuberculosis.

Fresh mountain air and almost year-round sunshine was also a clever marketing tool to lure cure-chasers to the region. A 1915 advertisement from the Colorado Springs Chamber of Commerce assured visitors:

“The climate of Colorado contains more of the essential elements which effectively promote health than that of any other country. These requisites are found in the chemical composition of the atmosphere; in the dry, pure, clean, soft, yet stimulating breezes which quicken circulation and multiply the corpuscles of the blood; in the tonic effect and exhilarating influence of the ozone; in the flood of its life-giving germ-destroying sunshine …”

But rest, fresh air, and sunshine would only do so much. Three times a day, patients were prescribed hearty doses of rare meat, raw eggs, milk, and rye bread to boost their immune systems. This diet was meant to fatten them up if they had suffered significant weight loss. The schedule patients followed was rigid but mandatory if they wanted to continue receiving treatment at the sanatoriums. Witherow reveals a typical daily schedule recorded in patient Emeline Hilton's journal:

"Six a.m.: Sister brought a glass of milk Seven a.m.: Took temperature and pulse before rising; cold sponge bath Breakfast: Rare beef, two raw eggs, 'heels' of rye bread and one pint of milk 8:30-12: Out-door inactivity in the sun; temperature and pulse; glass of milk at eleven; rest in room till dinner Dinner: Rare beef, one raw egg, rye bread and a pint of milk 1-5:30 p.m.: Porch, with 4 o’clock interruption of record (charting of temperature and pulse) and milk and room till supper Supper: Rare beef, one raw egg, rye bread and pint of milk 7:30: Bed and lights out 9 p.m.: Record (charting of temperature and pulse) and milk, if awake"

According to Witherow, the “forced-feeding” method seemed to work for Hilton, a patient at the Glockner Tuberculosis Sanatorium, who referred to her days spent there as “Rare, Raw, and Rye, and a gallon of milk each day.” Hilton's weight increased from 108 to 147.5 pounds after a year of treatment. (One might ask why patients were served rye bread as opposed to any other kind of bread. “The prevailing belief was that the darker the bread, the more nutritious. The goal was to add as much weight onto the patient as possible, and rye bread in particular was thought to be healthier, filled with nutrients, and denser,” Witherow says.)

Tuberculosis Huts Today

While tuberculosis sanatoriums helped some patients beat their symptoms, the development of effective antibiotics in the 1940s finally provided a cure for the disease and made the facilities obsolete. When the sanatoriums closed, the tuberculosis huts were sold off rather than demolished, which is why several still stand today.

While some were put to public use, like the hut that was converted into a visitor center at Rock Ledge Ranch Historic Site, others serve solely as historical landmarks. One hut still stands by Glockner Tuberculosis Sanatorium, which is now Penrose Hospital. Another renovated hut from Woodmen sanatorium resides at Mount St. Francis and serves as a monument, furnished like it would have been when patients lived there. In addition, the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum has a year-round exhibit called City of Sunshine, which not only includes a hut adorned in period style, but also displays experimental medical instruments, 19th-century exercise equipment, and a pharmacy exhibit filled with patent medicines.

Whether used as a storage shed or a museum exhibit, tuberculosis huts are a significant part of the city’s history. “I keep my eyes on them because I want to make sure they’re cared for,” Mayberry says. “They’re an artifact of our architecture in Colorado Springs and it’s an important reminder of who we used to be.”